Science and Medical Writer

jkling@gmail.com

Bellingham, WA

Home

Medical Writing

Science Writing

Writing Samples

My Career Path

Philippines

Sheepherding

The Key Peninsula Trial: Our First Competition

The rain streams down over the fenced pasture. It’s 8 am and I feel the chill of damp clothes. In another nearby field, Ivy, I, and Rodeo had slept lightly in a tent pitched among RVs and trailers, listening to the constant patter of raindrops striking the tent walls. I’m still a little sleepy as I stand beneath a canopy with other handlers and their dogs.

We’re the novice handlers, the amateurs who have just begun this deceptively complex sport. The advanced ‘open’ class competed the previous two days. Many of the experienced handlers have left, determined to beat the Memorial Day traffic to return to home and family. The serious competition is over.

11 of us novices huddle under the canopy, standing or sitting in camp chairs, accompanied by a few friends, family members and a couple of more experienced handlers there out of curiosity or to watch a student, and of course our dogs. They sniff each other or play, or wander about in search of a nugget of something edible, or some affection from one of the spectators. Some pause to watch the sheep in the field, but then return to these other pursuits. Only Rodeo stays motionless, facing the field, riveted by the sheep. He will not take his eyes off them until I urge him away.

Close by, the judge and secretary sit in the bed of a pickup truck, sheltered by another, smaller canopy, positioned for the best view of the proceedings. The judge’s chair is cushioned with the rare luxury of a sheepskin.

I watch the other runs, mentally critiquing them and trying to calm the bubbling tension I feel. Soon enough my name is called. I’m on deck. I call to Rodeo, who is still there, glued to the fence. “Rodeo, come.” He looks at me and then turns right back to the sheep. “Rodeo! Come!” I say with a little more force, and after about the second or third time I repeat it, he reluctantly turns away and follows me.

Soon enough, he realizes that something better is afoot, and he grows more animated with every step. It’s time to go to work, and like most border collies, he is endlessly keen to begin. We walk to the gate, close to the judge’s truck, and await our turn. When the previous handler finishes her run, and the three sheep have been taken off the field to the exhaust pen, I open the gate and we walk straight out to a red construction cone that marks the handler’s post.

We have three minutes to complete the course. First Rodeo is to bring the sheep to me during the gather, and next we’ll head to the nearby pen, where we will try to coax the sheep into a 10’ x 10’ enclosure.

A setout man wearing a wide-brimmed hat emerges from a gate on the right hand side of the field, followed by a packet of three sheep who are lured by the handful of grain he carries. He walks to the setout point, about 50 yards straight ahead, and spills the grain on the ground. Rodeo watches with his usual intensity, his body taut and ready to spring into action. But he’s a good boy and waits for a command from me.

The sheep settle and begin to dine on the grain. It’s up to me to decide when to begin the run. In the handler’s meeting, the judge advised us to start as soon as the sheep have settled around the setout point, because the longer they stay there on the feed, the more reluctant they will be to move.

So I give Rodeo an ‘away’ command. It’s short for ‘away t’me,’ the traditional Scottish command that translates to counter-clockwise. Rodeo immediately springs up and casts out in a nice, wide arc. This is the outrun, and it’s critical. By running in a big semi-circle, giving the sheep a wide berth, he avoids upsetting them. Ideally, he will run all the way around to the opposite side of the sheep, then slowly walk into them to begin the lift and fetch, during which he should bring them back to me in a straight line.

Ideally.

That’s not what happens.

The trouble starts when Rodeo reaches about 2 o’clock. The sheep begin to drift to the left, away from the setout man. Rodeo’s outrun hasn’t been quite wide enough, and he’s caused them to move off in the opposite direction. This isn’t a disaster. If he reacts by casting out wider, he can still complete a pretty good gather, though we’ll lose some points.

Since Rodeo is inexperienced, the best strategy would be for me to give him a ‘lie down’ command and then another ‘away’ command. This works well enough during training. Given a moment to stop and think, he usually casts out wider when given another flank command.

But this is my first trial. Nerves and inexperience cause me to freeze, and things begin to unravel. Rodeo ‘hitches’: he alters his course and begins trotting in a straight line towards the sheep. I’ve been watching the sheep, so I don’t notice this subtle change of direction. Instead, I watch uncertainly, aware that something is wrong but unsure what to do about it, as the situation gradually spins out of control. The sheep drift, Rodeo increases his speed, and they run faster in response. The next thing I know he has buzzed them – that is, he has sliced in, turning them back towards me, but over-running them so that he is out of position, and they amble back in the beginning of a zigzag pattern.

I am finally roused to action, yelling ‘lie down! Lie DOWN! LIE DOWN!!!” in a fruitless, escalating and far too tardy attempt to regain control of the situation. Rodeo is too excited and distant to heed anything I say, but he swings back around and intercepts them again, this time giving them more distance, and they stagger back again in my direction. After a few moments, he completes the gather and the sheep settle at my feet.

It's not a good start to the run, and I know we’ve already lost too many points to have any chance of placing high, but at least we can work on completing the pen. I give Rodeo a down command and walk the twenty yards or so to the pen. The sheep follow me. During several of the previous runs, the sheep had gone straight to the mouth of the pen, giving the handler a good opportunity to complete the pen quickly and with a minimum of fuss. But most of the time the teams failed the first attempt. When the handler paused to take hold of a rope attached to the gate, and the sheep moved past the handler into the mouth of the pen, the dog, fearing that they would escape, ran around to the other side of the pen to cover them. The handlers tried to prevent it, but the dogs were too anxious and ignored the commands. In response, the sheep did what sheep do – they move away from the dog, and that took them out of the mouth of the pen and back into the field.

I am confident Rodeo won’t have that problem because in our training sessions he is very calm and responsive during penning, and I think he will lay down behind the sheep and hold his position there until I ask him to walk up and put pressure on the sheep to force them into the pen.

But we immediately run into another problem. The sheep don’t settle at the mouth of the pen. Instead, they go around the pen and settle behind it. I take hold of the rope attached to the gate of the pen – a tactical error because, once I take the rope, I cannot let go of it again until the sheep are successfully penned, and that means I can’t walk out into the field and help Rodeo if he needs it.

I send him after the sheep to bring them back around to my side of the pen. He heads out to gather them up and does a pretty good job of casting wide to get around them. Then they move back to my side of the pen, and the problem in the outrun repeats itself. The sheep move past me and Rodeo becomes anxious, afraid of losing them. Instead of casting out wide, which would have allowed him to gather them to me at the front of the pen, he panics and comes in tight, trying to cut them off quickly. As on the outrun, this only riles them up more and causes him to overshoot them.

Again, this is my error. I should correct him when I see him start to come in too tight. I could have laid him down and then given him another ‘away’ (counterclockwise) command, and there was a good chance he would have kicked out and gathered them more calmly.

Just as with the outrun, Rodeo recovers and manages to bring them back to me at the mouth of the pen. It looks like we’ll get our chance at it. The two light colored sheep come to the mouth of the pen, but the dark one splits off and goes behind the pen again. I send Rodeo after it, but it’s no use: the two light colored sheep quickly totter off to the exhaust pen, and we are forced to retire. No points scored.

Rodeo is still trying to gather the rebellious black sheep. “That’ll do,” I call, and he comes to me, understanding that his work is done for now. I walk off the field, shaking my head in frustration. This is not how I envisioned our first competition.

On our way back to the canopy where Ivy and our friend Judy have been watching the proceedings, we pass the judge’s truck. The secretary, whose job is to ensure that scores are properly scored, leans down for a consoling word.

He tells me that I handled myself well because I never lost my cool. He also says it was the right decision to retire, because once the sheep were split, there was almost no chance of getting a pen. I could have continued until our three minutes were up and been granted a partial score, but I couldn’t see the point. The score would have been low, and there was no sense in stressing the sheep out any more than they had been. It’s not kind to the sheep. Trials are a rough day for them, especially when they’re dealing with inexperienced dogs. And it’s not fair to the competitors who will have to work with these sheep later in the day.

I walk past the judge’s truck and to the tent, where Ivy and Judy say kind words, and I watch more teams and smolder inwardly, replaying our run in my head. Rodeo resumes his position near the front of the canopy, staring intently at the sheep, enjoying the country life as only a Border Collie can.

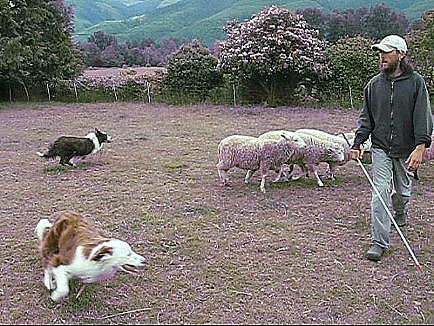

That's Rodeo in the foreground, taking instructions from our trainer Dirk. His dog Amos is in the background.

Rodeo putting pressure on the sheep.