When Horses Really Walked On Water

by Sid Perkins

Before the steam engine was invented, there were

three sources of usable power: wind, water, and animals.

The first of these to be harnessed -- literally -- was animal.

This feature story appeared on pp. 90-92

of the May 21, 1999, issue of

The Chronicle of the Horse.

On land, humans in cultures throughout the world have used horses, oxen, donkeys and other domesticated animals to pull everything from plows to sleds. Horses alone, however, became the backbone of man's transportation network -- their combination of speed, endurance and demeanor made them the prime mover for everyone from Roman charioteers to marauding Mongol hordes.

On the waters, however, it was a different story. Most people simply don't think of animals as a likely source of power for boats. Those that do probably recall horse- or mule-drawn barges like those used on the Erie Canal in the 1800s. But a much more common -- and yet almost unknown -- form of American transportation from that same time period was the horse-powered ferry.

Several different types of these amazing boats, which usually used teams of two or more horses as their "engine," plied the waterways of North America from the 1790s until the late 1920s. The horse ferries were most plentiful more than 150 years ago, however, and consequently have been forgotten by many.

In 1983, nautical archaeologists discovered what they suspected to be a horse-powered ferry on the bottom of Vermont's Burlington Bay. Researchers spent portions of four consecutive summers diving on the well-preserved wreck, years studying the data they obtained, and more than a decade unearthing the often hard-to-find history of these horse-powered marvels.

Kevin J. Crisman, an associate professor of nautical archaeology at Texas A&M University, and Arthur B. Cohn, director of the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum in Vergennes, Vt., were two of the archaeologists who excavated and studied the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry. The fascinating results of their research were published in the summer of 1998 in the book When Horses Walked On Water: Horse-Powered Ferries in Nineteenth-Century America.

Early Ideas about Animal Power

Europeans were the first to build watercraft powered by animals. Roman engineers had designed an oxen-powered boat as early as the 4th century A.D., but no records show if that boat -- or one like it -- was ever constructed.

Crisman and Cohn's research indicates that the first animal-powered vessel to make it off the drawing board was a horse-powered boat built in England around 1680 by a cousin of King Charles II. This boat, or one of a similar design, later served as a towboat in one of the Royal Navy's dockyards, where the craft (powered by four to eight horses) was reportedly capable of towing even the largest ships in the Royal Navy.

Although the English towboat proved that the concept of animal-powered watercraft was feasible, this experiment -- as well as others that took place in Europe during the 18th century -- failed to stimulate a lasting revolution in boat design.

At that time, most areas of Europe already had a well-developed system of roads, bridges and canals. In places where ferries were needed, boats powered either by sails or by human muscle had been operating efficiently for hundreds of years. Also, a relatively dense population ensured that the manpower needed to power such boats was both plentiful and cheap.

But Crisman and Cohn note that Colonial America had none of these benefits. As the United States entered the 1800s, it had a relatively small population that was spread across a broad, rugged landscape. There were no roads into the frontier; explorers and settlers used America's waterways as their highways and ferryboats as their bridges. The manpower to row such boats was scarce, and the winds needed to drive sailboats weren't always reliable.

To help solve these problems, Americans turned to technology. Both steam- and horse-powered boats were first introduced to American waterways in the late 1780s and '90s, but the commercial success of either wouldn't come for another 20 years. And even though the steamboat represented a more advanced technology, it did not immediately make the horseboat obsolete. Ironically, in several ways the steamboat provided a major incentive for the horse-powered boat's further development.

First, state and local governments sought to encourage the rapid development of steamboat technology; they often did this by granting long-term monopolies on steamboat navigation routes to inventors or businessmen who were the first to successfully establish a steamboat company or ferry.

Second, the steamboats created the expectation of speedy and regular service. Once the steamboat monopoly was in place, potential competitors had no choice but to resort to other sources of power, the most reliable of which was animal power.

Early American Horse-powered Boats

Horses powered the earliest generation of American horseboats by walking in circles on the deck about stationary posts, or whims. This type of mechanism had been used on land for thousands of years for a variety of purposes, such as grinding grain, pressing olives, and pumping water.

On the horse-powered boats, however, the power from the whims drove various types of propulsion devices. Although some used screw-type propellers or duck-leg paddles that moved to and fro, most of the whim-type ferries used paddlewheels to propel the boat.

Crisman and Cohn found that the whim-style horseboats operated in many parts of North America, including Halifax, Nova Scotia; Philadelphia, Pa.; Washington, D.C.; and St. Louis, Mo.

In New York City, horseboats successfully competed with steamboats in the thriving business of ferrying passengers from lower Manhattan to Brooklyn and to New Jersey. At least eight different horseboat ferry routes operated from docks in southern Manhattan in the years between 1814 and 1819.

Newspaper accounts from the time tell of one ferry, powered by eight horses, that could carry more than 200 passengers across the East River in 8 to 18 minutes, about the same time it took a steamboat to travel the same route.

The financial advantages of a horseboat were obvious: While a steamboat could cost about $30,000 to build, a horseboat -- complete with extra horses and a stable on shore -- could cost as little as $12,000.

Even though horseboats were much cheaper than steamboats, they still had their disadvantages. The whims and the circular walkways for the horses took up a lot of deck space. To solve this problem, designers often built a catamaran-style boat with one wide deck atop two small hulls. Even with a wider deck, however, the horses had to walk incessantly in small circles, which wasn't good for them.

An innovation patented by Barnabas Langdon in 1819 -- the treadwheel-propelled horseboat -- solved both of these problems.

Langdon placed a rotating turntable slightly below the level of the boat's deck; horses stood atop the turntable through large slots in the deck and drove the wheel backward by walking in place. This design eased the burden on the horses, freed up valuable deck space, and allowed the ferry to be built atop one hull.

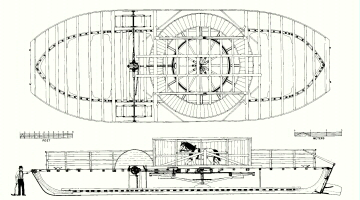

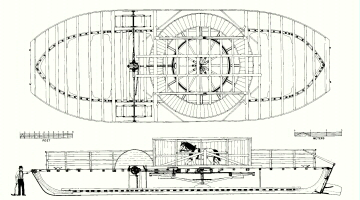

Sketch by Kevin J. Crisman

Sketch by Kevin J. Crisman

Cross-sectional view and top view (with deck planking removed) of the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry, which show the horizontal turntable beneath the boat's main deck.

Horseboats that used the horizontal treadwheels were both reliable and cheap, and they quickly became the most common type of horseboat for more than 20 years. They were used well into the 1850s in many locations in New England and the Mid-Atlantic, and at least a dozen such ferries crossed the Hudson River.

Treadwheel horseboats were also used to cross Maine's Kennebec River and to ferry passengers between the islands in Rhode Island's Narragansett Bay.

In the early 1830s, inventors began to develop horse-powered inclined treadmills that farmers could use, with various attachments, to saw wood, churn butter, and pump water. Manufacturers began to produce these devices in large quantities in the 1840s, and competition for business caused the price of treadmills to drop steadily.

Sketch from an advertisement in the June 1852 issue of Cultivator

Sketch from an advertisement in the June 1852 issue of Cultivator

Inclined treadmills were originally invented in the 1830s as labor-saving devices for the farm, but they were soon adapted to serve as a power supply for paddlewheels on boats.

Most of these treadmills were light, portable, cheap, and easy to maintain because replacement parts were readily available. The treadmills revolutionized the design of horse ferries: They could easily be attached to the sides of a boat's hull and need not be "built-in" beneath the deck like the horizontal treadwheels.

Most of these new horse ferry designs had two treadmills, with one on each side of the boat driving its own paddlewheel. But there was one drawback of this design: If the horses walked at different speeds, the paddlewheels would turn at different rates and the boat would travel in large circles!

Ferrymen found ways to overcome this disadvantage, however, and inclined treadmills, due to economics and ease of maintenance, powered most horseboats built after 1850.

The Decline

The Northeast was heavily industrialized by the 1860s. In the last years of the 19th century, bridge construction and the ever-expanding network of railroads led to an inevitable decline in the number of horse ferries. Then the internal combustion engine -- the power source that also doomed the steam engine -- was the final nail in the horse ferry's coffin.

Crisman and Cohn say that the last horse ferry to operate in North America may have been a small treadmill ferry powered by a single blind horse, which provided the "horsepower" to shuttle passengers across the Cumberland River at Rome, Tenn., until the late 1920s.

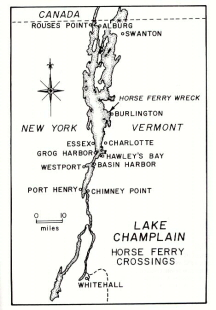

Lake Champlain in New York was "discovered" by French explorers in 1609. And a significant amount of this country's early nautical history took place on this long and narrow lake, which forms much of the border between New York and Vermont. Lake Champlain hosted numerous naval battles between French and British ships during the next 150 years.

The fledgling U.S. Navy, which was first established at the southern tip of Lake Champlain in 1776, fought British warships on the lake during both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

In June of 1984, underwater archaeologists sponsored by the Champlain Maritime Society and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation conducted a sonar survey of Lake Champlain to locate and inventory its shipwrecks. The researchers chose to focus part of their survey in Burlington Bay, Vt., because the area was a commerce hub in the 19th century. Several wrecks had already been found in the bay, including a variety of sailing craft and canal boats.

One wreck, however, was of particular interest to the scientists. During the previous summer, a privately-sponsored sonar survey had discovered an unusual wreck: a boat that had a pair of paddlewheels but no evidence of a boiler or steam engine. In their report to Vermont's state archaeologist, they suspected they had stumbled upon a horse-powered ferry.

The 1984 expedition found that the wreck, which lay in about 50 feet of water in the northern part of the bay, was wonderfully preserved. The sonar showed that a seemingly complete arrangement of iron gears and shafts led from the paddlewheels to a large, spoked wheel that lay beneath the boat's deck. Scuba divers photographed the entire wreck that year, but little additional fieldwork was conducted for another five years.

In September of 1989, Vermont's Division of Historic Preservation initiated a four-year program of detailed archaeological study at the site. Four scuba divers took measurements, and they studied the treadwheel-paddlewheel propulsion system.

In 1990, divers removed sediments from the inside of the bow and found artifacts, including fragments of a horse collar, pieces of leather harness straps, and several broken horseshoes. The size of the shoes and the general design of the boat indicate that two small or medium-sized horses powered the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry.

Further excavations the following summer yielded two clues about what may have happened to this boat on the fateful day it slipped beneath the lake's surface.

Divers found a spot on the hull where a section of plank was missing, although there was no damage to nearby sections of the boat. Also, the divers found the ferry's rudder lying under sediments in the bow, about 60 feet from its normal location at the rear of the boat.

Crisman and Cohn say that these facts indicate that the ferry probably was towed just outside the main harbor and then intentionally sunk by knocking a hole in the bottom of the boat.

Other factors point to a deliberate scuttling of the boat. First, Burlington Bay is located at the widest portion of Lake Champlain, and therefore it is highly unlikely that a ferry powered by only two horses operated from this point on the lake. Second, the ferry showed many signs of a long lifetime of heavy use, including heavily worn gears and a hull that had been worn to only 1/2-inch thick in places.

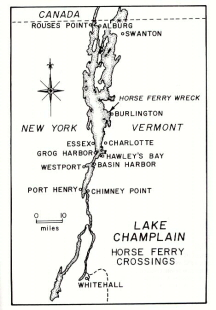

Sketch by Kevin J. Crisman

Sketch by Kevin J. Crisman

A number of horse ferry routes crossed Lake Champlain, but none were known to have operated from Burlington, Vt., which is located at one of the widest spots on the lake.

In 1989, the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry became a part of Vermont's Underwater Historical Preserve System. The ferry received added protection when it was added to the National Park Service's National Register of Historical Places in December of 1993. Today, the sunken ferry is visited by hundreds of scuba divers each year.

Crisman and Cohn say that the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry is the only surviving example of a horse-powered vessel anywhere in the world.

Their research, which was spurred by the discovery of a waterlogged wreck that laid beneath the murky waters of Burlington Bay for almost 150 years, has brought to light an almost forgotten mode of transportation used in a far simpler time.

The very thought of a horse-powered ferry brings to mind an era when American technology was young -- a time when people transported their goods by stagecoach and by wagon, a time when the Pony Express surrendered to the telegraph, and a time before the Oregon Trail gave way to the railroad, the minivan and Interstate 80.

For More Information:

The book When Horses Walked On Water: Horse-Powered Ferries in Nineteenth-Century America, by Kevin J. Crisman and Arthur B. Cohn, is available from the Smithsonian Institution Press. A clothbound hardback edition costs $37.50. To order, call 1-800-782-4612.

For additional information about the Burlington Bay Horse Ferry and other archaeological sites in Vermont's Underwater Historical Preserve System, contact:

Vermont Division for Historic Preservation

National Life Building, Drawer 20

Montpelier VT 05633-1201

Phone: 1-802-828-3050

Lake Champlain Maritime Museum

RR 3, Box 4092

Vergennes VT 05491

Phone: 1-802-475-2022

---[

Copyright 1999 by Sid Perkins

All rights reserved.

---[