We are still collecting experiences for our COVID-19 Time Capsule. Please share how you are feeling by submitting an entry here: bit.ly/sw20sum30.

“Mum! My Zoom isn’t working and it’s time for my class meeting. Can you help?”

“Mum! My Zoom isn’t working and it’s time for my class meeting. Can you help?”

The panicked plea from my 8-year-old interrupts my typing mid-sentence. “Hold that thought,” I tell myself. It’s gone before I’ve left my seat.

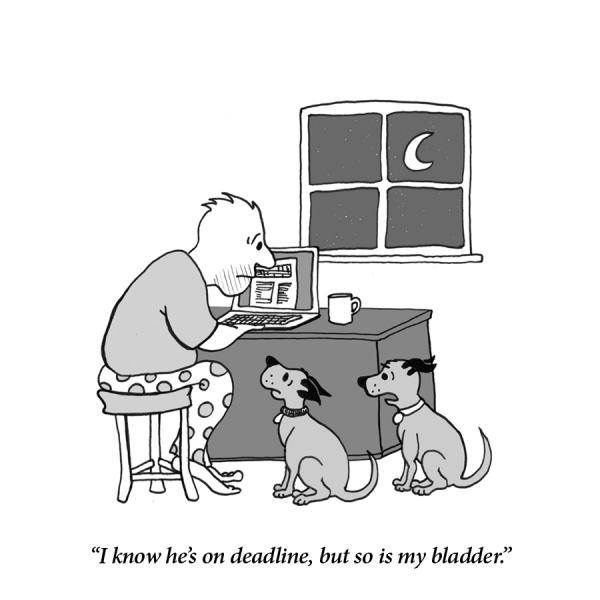

I trudge over to my son’s desk (aka the coffee table), tackle the laptop problem by restarting it and crossing my fingers, and turn back toward my office (aka the dining room). On the way, I scoop up a discarded plate of toast the dog is eyeing and kick a stray shoe into a corner before “someone” (probably me) trips over it.

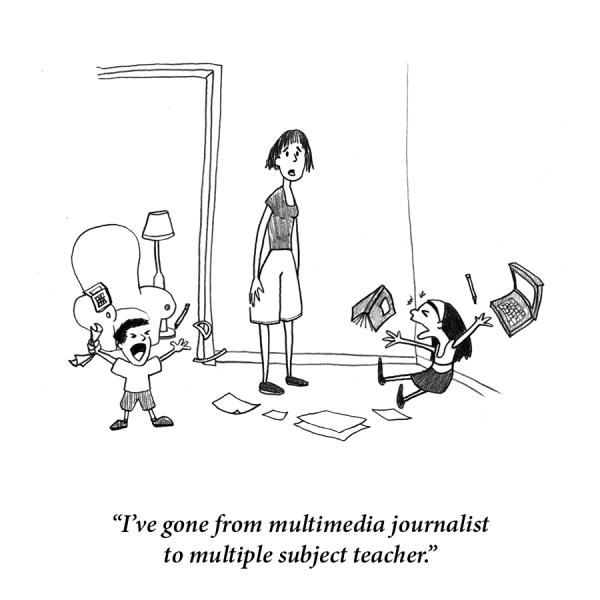

It’s early April of 2020, just two weeks since coronavirus-related lockdowns began in California, where I live, and many other states. Since then, homes have become offices, parents have become teachers, workloads have mushroomed (or shriveled), internships have been canceled, and anxieties have gone through the roof. Not to mention the emotional pains from the collective weight and renewed attention of another, already present plague: systemic racism.

Amidst this chaos and uncertainty, science writers have stepped up—to report on the pandemic, manage communications for their institutions, and lead science outreach efforts. To do so means embracing the 24-hour news cycle and overcoming feelings of burnout and fatigue to provide responsible and accurate coverage of rapidly unfolding events.

In April 2020, we began asking members to share their honest and frank experiences of living and working through the pandemic. Their responses are a time capsule for this moment— a collection that will give future science writers insight into our present-day realities.

Thank you for helping us capture this glimpse of history. And stay safe.

— Sarah Nightingale, NASW digital & print editor

2021 entries by:

2021 entries by:

Matt Shipman

David Levine

Ashley Belanger

Chanapa Tantibanchachai

Erin Garcia de Jesus

Leah Rosenbaum

Ellen Kuwana

Clinton Parks

Jane C. Hu

Helen Santoro

Iqbal Pittalwala

Kendall Powell

Jyoti S. Madhusoodanan

2020 entries by:

Jane C. Hu

Jane C. Hu

Matt Shipman

James Urton

Chanapa Tantibanchachai

Erin Garcia de Jesus

Iqbal Pittalwala

Natalie Rogers

Marla Broadfoot

Erika Check Hayden

Mary Miller

Bryn Nelson

Erin Ross

Ashley Belanger

Amy Maxmen

Ellen Kuwana

Calley Jones

Helen Santoro

Jonathan Wosen

Clinton Parks

David Malakoff

Gina Mantica

David Levine

Theresa Machemer

***

Jane C. Hu

Independent Science Journalist

@jane_c_hu

April 20, 2020

Today is my 36th day of self-isolation and the umpteeth I’ve spent thinking about coronavirus. While so many are out of work, I’m grateful to have a job where I can work from home—and for the opportunity to inform the public, to provide experts’ answers to frequently asked questions about the virus, and to counter misinformation with facts.

At the same time, I often feel overwhelmed; the news changes hourly, and coronavirus touches every aspect of our lives, which means there are endless stories to report and write. Even when I’m not working, I’m reading other journalists’ stories to keep up with developments, poring over research papers, and, when I can, trying to share what I know with friends and family, either over the phone, or via social media. (Social media, in particular, has been infuriating— rumors and incorrect info spread widely, and uninformed opinions somehow always crowd out actual expertise.)

All the “self-care” tips I’ve seen about staying mentally healthy during this pandemic have suggested limiting your media consumption, but it’s difficult when staying up on all the news is part of your job. I’ve tried to maintain good boundaries around my work, like leaving my phone in another room after 10pm and prioritizing exercise, but there have been many nights where I’ve had trouble sleeping. It doesn’t help that I’ve gotten some hate mail in response to some of my reporting; as a result, I spent a few hours last week locking down my online accounts and preparing myself for harassment. On top of this, I feel guilty worrying about these relatively small issues when so many people are sick and dying; these problems pale in comparison, and I’m trying to keep it all in perspective.

***

Jane C. Hu

Independent Science Journalist

@jane_c_hu

February 16, 2021

I wrote my first COVID piece in early February 2020, and I can hardly believe that was more than a year ago. On the one hand, it feels like just yesterday; on the other, pre-COVID feels like a lifetime ago. This morning, I saw a headline that new US cases had dropped to 90,000 a day for the first time since November, which led me to look up how many Americans have gotten COVID: over 27 million, according to the CDC. It's incredible that at least 8% of the country has had confirmed cases.

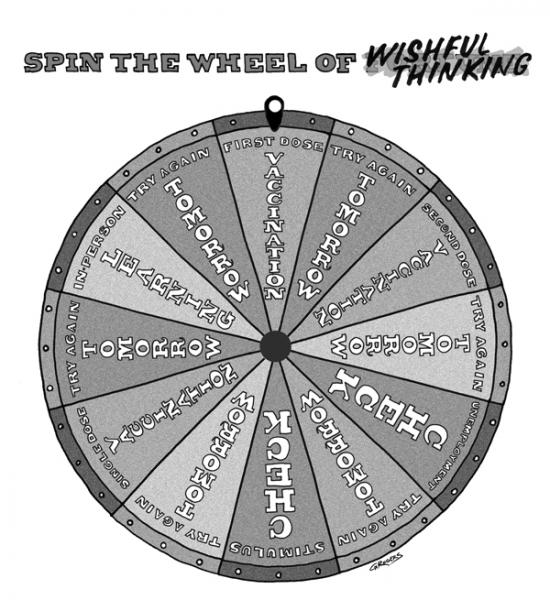

The dominant feeling among my friends and colleagues is exhaustion. I started interviewing sources about vaccines back in December, back when we were hopeful some of the shortcomings of the system would be shored up. Unfortunately, that hasn’t been the case, and it has been dismaying to see all experts’ predictions about vaccine rollout challenges come true. I’ve pitched a couple features that would, in an ideal world, involve some domestic travel, but any plan to do so feels tentative at best, especially with the threat of new variants spreading. Based on my state’s vaccination rollout and my position in the queue, I’d be lucky to be vaccinated by fall. Logically, I know the pandemic won’t last forever, but sometimes it really feels like it will never end. I’m also currently reporting on global vaccine inequities, and it’s sobering to see reports that estimate some countries won’t have full access to vaccines until 2024.

Though the isolation is getting old, I’m still grateful for the privilege to work from home, and have been trying to use this period of relative solitude to work on longer-term projects, and to build better habits around hobbies like running and studying Chinese.

***

Matt Shipman

Research Communications Lead, NC State University

@ShipLives

April 20, 2020

Tuning out the news is good advice for folks who are feeling overwhelmed or anxious during this crisis. But if you’re a reporter, editor, or PIO, that’s often a luxury you can’t afford. Following the news is part of the job, and that has been kind of tough lately. On the other hand, being able to throw myself into writing about issues pertaining to COVID-19 was almost a relief. It gave me something to focus on, as well as a way to feel productive and useful during a situation in which I felt largely powerless.

I’ve also found myself writing open journal entries online about my experiences and observations, just to get them off my chest. I thought of it as the ultimate in navel-gazing, to be honest with you. But I’ve been contacted by a lot of folks who thank me for sharing. I think the desire to feel connected with other people has been heightened by this crisis, and the written word is still a powerful means of establishing that connection.

***

May 21, 2020

I am aware of the importance of having a positive attitude. I am also aware that it can be very difficult to have a positive attitude right now.

Having a positive attitude is not about being some sort of Pollyanna where everything is okay all the time. For me, having a positive attitude is about trying to find moments of grace as they come, while being prepared to deal with whatever might happen next. It’s about acknowledging all the things we don’t have control over and trying to let go of some of that stress – while also hustling to make sure that you have what you need.

Man, letting go of that stress is so hard right now.

I try to be grateful for even small things and I try to engage with the world. Engaging with other people brings me laughter and hope and joy, which is good. But it also often leaves me frustrated, angry or despondent at how many people refuse acknowledge the gravity of our circumstances -- or to take even simple steps that could save someone else’s life. Even worse are those who go out of their way to attack people who are being considerate. It’s just so disheartening. I increasingly find myself wanting to retreat inward.

So there’s a struggle to find balance between remaining engaged – which is a practical and professional necessity – and giving myself the necessary space to ensure my mental and emotional health. I suspect a lot of us are grappling with that.

***

Matt Shipman

Research Communications Lead, NC State University

@ShipLives

February 5, 2021

Over the past year, I've been astonished at how smoothly my professional life has transitioned to working from home. I know that I'm incredibly fortunate in this regard, and I am grateful. For the most part, my work routine has not changed -- meetings with editors, researchers, etc., still take place. The only change is that now they take place online. That said, I find things harder now than I did in the early stages of the pandemic. Maybe I'm just worn down? I think it comes from seeing so many people behaving so selfishly for such an extended period of time. e.g., the people who not only refuse to wear masks, but attack those who do wear masks. It's disheartening and exhausting. I was holding up fairly well until January 2021. Since then it's been a little bit more of a slog. I just keep telling myself that the only way out is through and focusing on doing my work, caring for my loved ones, and -- as clichéd as this sounds -- taking things one day at a time.

***

March 17, 2021

The past couple of weeks have been remarkable. North Carolina, where I live, made university workers a priority group for vaccination. As a result, many people I know were vaccinated in a short period of time. Hearing that steady drumbeat of good news from friends and colleagues has been incredibly heartening. The pandemic is far from over, but for the first time in more than a year I find myself willing to imagine that the end is within sight—if distant.

***

James Urton

PIO and Science Writer, University of Washington

@jamesurton

April 20, 2020

When I tell people that I have felt anxious and afraid about COVID-19, they often assume that I’m concerned about catching the coronavirus, or that someone I love will end up in the hospital. It is true that I am concerned about these possibilities. But I can manage those fears. They do not overwhelm me.

Instead, I have learned that strain can sometimes rupture faults in unexpected places. To my surprise, the angst and dread that have at times consumed me over the past month do not stem from this virus, its pandemic or the disruptions to our health and way of life. It turns out that cutting myself off so abruptly from my day-to-day routine exposed deep, fundamental insecurities about my identity and character—Do I matter? Is what I want okay? Am I good?

Before the pandemic, I unconsciously structured much of my life around a frenetic desire to outrun these questions and their antecedents. Over many years, I grew into an increasingly unbalanced equation. But the abrupt cancellation or postponement of my routines and social circle left me violently exposed. This past month, I came face to face with a seemingly monstrous remainder to that equation—and I could no longer run from it.

The anxiety breached my life with the sudden violence of a deluge. But I am luckier than most. I have access to resources that helped guide me, as well as the grace and understanding of family, friends and colleagues. I also have privilege, which has so far buffered me against much of the economic downturn and provided me with time and space to improve my mental well-being. This torrent left me damaged. But I feel secure again, and have enough confidence and support to start on repairs—and improvements.

***

May 25, 2020

You will ask, “How are you holding up?”

“I’m okay, thanks,” I’ll reply. “And you?”

In truth, it’s complicated. I recently learned that my brain works differently from yours, which means that your question won’t make me feel cared for or loved. I won’t think that you’re kind to ask. I won’t experience a fraternal connection between us for living through this pandemic.

Instead, my mind will channel your heartfelt question directly to its record-keeping center, where I will be found wanting. My many pandemic shortcomings will wash over me in waves: the strangers I let into our home to fix what I can’t; the paycheck that feels small; the smoke alarm that goes off each time I cook for my family; the day I forgot to bring hand sanitizer to the grocery; the boyfriend I can’t cheer up with a carefree vacation; the boxes still unpacked five months after we moved; the job I fear losing; my city and state, both so unprepared for the coming economic and political shockwave; the planet I kill one bag at a time.

My mind thinks that revisiting the past like this will help protect me from future mistakes. But over time, this process became canalized: All I do now is feel these failures, and scramble to get away from them.

I wish I could answer your question by sharing this with you. I yearn for you to know that I still smile and laugh and love, but under this cloud. I wonder: Maybe we could even accompany one another through our vulnerabilities, perhaps helping me forge a path in my mind that is more charitable than its current course.

Instead, I hear your question, inhale through my weighted chest, and say, “I’m okay, thanks. And you?”

***

Chanapa Tantibanchachai

Media Relations Representative, Johns Hopkins University

@chanapa_t

April 26, 2020

Tomorrow marks the start of my seventh week working from home. At work, things have roughly settled into a “new normal,” though it never feels any less crushing. Even though we don’t field media requests for the public health experts or physicians in the central JHU comms office, our days are still consumed with COVID-19.

Of course, there’s the infamous COVID-19 tracking map our engineers created, but there’s also the slew of COVID-19 institutional and community messages about virtual commencement, online classes, rebates, etc., that need to be vetted and distributed.

Last week Hopkins announced austerity measures after estimates showed we’d have to cut costs by $475 million through June 2021. I had naively believed an institution like JHU couldn’t be affected so seriously, so I’m now questioning the stability of other aspects of my life. Will my October wedding happen? I had been so confident up until last week but am now worried.

In my personal life, I’ve been consumed with worry for my parents as my dad enters his fifth or sixth week of unemployment. When Nevada closed all casinos, I immediately reorganized my financial spreadsheets to save more money for them. They spent nearly a month calling Nevada’s unemployment line hundreds of times a day before being able to file an initial claim.

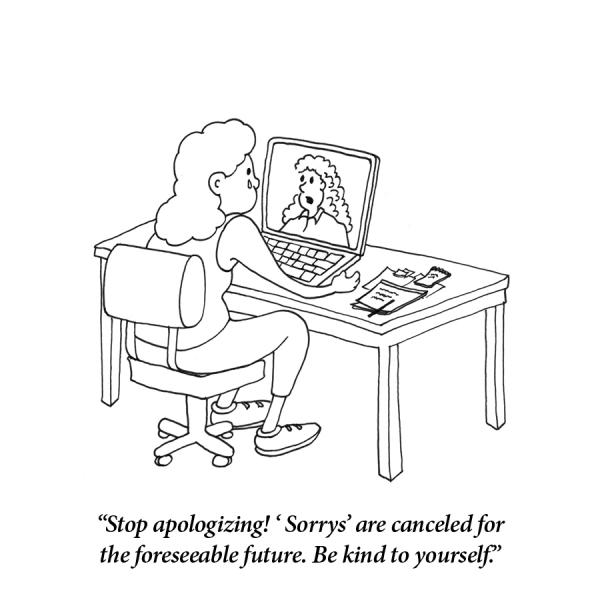

I’m fortunate in so many ways: my partner and I both remain healthy and gainfully employed, and we have no children to worry about. Even so, I’m overwhelmed and filled with dread most days, especially because the nature of my job doesn’t allow me to turn off the news. I can’t imagine how others are faring. I try my best to be gentle with myself and take it a day at a time, though, and that’s really all any of us can do.

***

The days seem to get longer but the months somehow shorter. I’ve more or less found a work-from-home rhythm, but I desperately miss having a defined space away from home.

As a science writer, I understand that we’re learning about the virus everyday and the rules/guidance change accordingly, but as a person, I am exhausted. The lack of certainty and the conflicting guidance from local and federal government about what we should be doing drains me.

I’m envious of the action my former coworkers over on the Medicine side are getting, connecting medical experts for dozens of stories everyday, while I try to make some obscure engineering angles happen, but I’m also grateful to not have that workload anymore. I remember even for one-off events, like the announcement that Melania Trump underwent a kidney embolization, and the mad scramble to fulfill dozens of requests.

The cancelation of ScienceWriters 2020 in October in Colorado (right next to Utah where my wedding will be) initially had me worried about my wedding, but I intend on proceeding as usual until the law tells me otherwise. Even if we downsize to a ‘microwedding’ with only immediate family, it’ll still require cross-country flying.

I’m trying to not worry about situations beyond my control, but it’s difficult when it feels like more and more slips out of my control each day. I guess that’s the theme of this entry and the biggest challenge I’ve had: uncertainty and loss of control. How will things look in a month? 6 months? If the law allows us to do something, is it truly ‘safe’ or not? How much risk am I exposing myself and others to if I do something that’s legally allowed but not fully backed by public health guidance? What do ‘safe’ and ‘risk’ even mean each day?

***

Chanapa Tantibanchachai

Press Officer, US FDA

@chanapa_t

February 5, 2021

Since my last entry, I started a new job as a press officer for the FDA, which has been incredibly busy but exciting. This also meant I finally got to leave my last, toxic job. It was such a strange position to be in: I had immense gratitude for a stable, high-paying job during the pandemic, but was desperate to leave for my mental health. But what right did I have to demand stability, good pay, AND respect, while people were/are losing their jobs and struggling to survive? This inner conflict was often amplified by my parents, who are low-wage immigrants with the mindset of “survive, not thrive,” so they don’t quite understand the need for fulfillment, equity, or growth in a workplace.

As I type this entry and am about to delve into my selected theme of how my pandemic experience has been one full of legitimate complaints that I feel are overall minor compared to others’ suffering, I receive news that both of my parents have COVID-19. I’m in shock. They sound chipper, albeit congested and tired, but my mind is spinning. Will they know to go to the hospital if it gets too bad, or will they hold off in fear of hospital bills and the hassle? What if they DO have to go to the hospital? They live in a small town with poor medical resources. If they needed serious care, they’d have to be airlifted to the nearest big town 1.5 hours away. What can I even do from 2,000+ miles away?

This entire year, I’ve been largely shielded from the virus’ most devastating effects: I haven’t lost my job, my home, or any loved ones. Now the risk of losing one of those feels more real than ever and I’m terrified.

***

Erin Garcia de Jesus

Staff Writer, Science News

@viruswhiz

April 27, 2020

Staying focused on one task has been a major challenge for me over the past few weeks. With information flying so fast, I’m always getting distracted by new research posted on Twitter or the latest COVID-19 press release. I feel like my productivity has taken a nosedive and I’m definitely not writing as many stories as before. But I know I’m not alone.

Unplugging from the deluge of coronavirus coverage is also a huge struggle. Even if I’m not working on a COVID-19-related story, there’s always another article to read or questions to answer. A few of my Facebook friends are spreading misinformation,

and I’ve lost the patience to deal with it. (Seeing posts about injecting disinfectants and UV light were the last straw for me, much to the delight of some of my close friends and family.) I keep telling myself I need to delete all social media apps from my phone, so that I’m not tempted

to compulsively check what people are posting. I also know that I’m the only virologist and science journalist some of them know, and I want to make sure the people in my life have the facts. But

I’m aware that I need to protect my own mental health, so I’ve been trying to balance it all out by reading novels with guaranteed happy endings or re-reading my favorite books from when I was a kid. Right now, there’s nothing like escaping into a good book right before going to bed!

***

June 2, 2020

Some days I feel like I’ve finally got this whole working from home during a pandemic thing figured out. I wake up, go for a run and enjoy a cup of tea with breakfast. (Who would have thought it would take a pandemic to turn me into a runner?) Then, I sit down, get to work and finish the day feeling like I’ve accomplished something.

Other days, I forget how to find stories and write them. On those days, I return from my run to find an empty page staring back at me, taunting me with questions like “don’t you know how to write a good lede?” or “wouldn’t someone else could do a much better job on this story?” I despair that I’ll ever write anything worth reading. Once I get those first paragraphs on the page and hit my stride the writing doesn’t necessarily get easier, but I at least remember that I am a competent reporter.

The one bright spot in all the chaos is that the pandemic moved up my plan to join my husband in Philadelphia, where he has been living since September. I miss D.C. — and hope to move back one day — but now we get to live under one roof (with one rent payment). Plus, we can finally adopt some cats, like we’ve been wanting to for years.

***

Erin Garcia de Jesus

Staff Writer, Science News

@viruswhiz

Februry 10, 2021

At the end of 2020, I knew that news about the coronavirus and the pandemic wasn’t going to go away as the calendar flipped to a new year. But I also felt hopeful that with the success of two COVID-19 vaccines — and the promise of more to come — things might slow down a little. The emergence of new variants threw me for a loop.

Before switching to journalism, I studied viral evolution. I spent a lot of time at the beginning of the pandemic reassuring people that viruses mutate all the time, so reports of new strains were likely overblown. Seeing many of the scientists in my field become more concerned about new coronavirus variants in the United Kingdom and South Africa in December was disconcerting.

My last story of 2020 was about B.1.1.7, the variant from the United Kingdom. My first story of 2021 discussed viral evolution in the face of vaccines. Things haven’t slowed down since.

Were I not coming off a full year of writing about coronavirus 90 percent of the time, the current pace might feel sustainable. But I’m exhausted, as is everyone else. I shouldn’t feel guilty that my brain feels like mush and it takes me hours to complete a task that should take me 30 minutes, but I do.

Of course, there are things to feel thankful for: My parents are vaccinated now (although there’s still no hope I will see them soon). The people in my family who have — so far — gotten sick with COVID-19 are all recovered with no major issues. I have incredible colleagues who make it possible to take a break when I need to. But the pandemic has certainly taken its toll.

***

Iqbal Pittalwala

Senior Public Information Officer, University of California, Riverside

@UCR_ScienceNews

April 27, 2020

We began working from home on March 16. The first two weeks were trying, exacerbated by the uncertainty that lay ahead. I have adapted to WFH now and am taking advantage of the extra free time the novel coronavirus has liberated. I take daily walks, video-chat with friends and family I haven’t connected with in months, catch up on podcasts, and binge-watch shows I didn’t know existed.

Still, some challenges remain: While Zoom interviews with faculty members are a viable option, they pale in comparison to chatting in person and struggling together to find lay language that explains the science. Another post-COVID-19 challenge is that the volume of electronic messages has grown; minor messages, once conveyed in person in the office, are now dispatched by email, Slack, or through other communication tools. Yet another challenge is securing media interest on faculty work with no COVID-19 ties.

The workload has remained steady – for now. I’m writing COVID-19 stories and still covering research done before the virus knocked us off our feet. How this will change in the coming weeks, with labs largely disrupted, is tough to predict. Hard to guess also is how budget cuts, approaching like an ominous cloud, will slow down the university.

Although WFH has several benefits, I miss the campus, its vitality and vibrancy. I miss the libraries, the noisy food court in the heart of campus, seeing students rushing to their classes. I miss bumping into researchers and socializing with coworkers. I certainly miss the 8-to-5 structure that outlined the workday.

I can’t complain. We are the lucky ones. Unlike millions of people, we get to WFH and are functioning well. Post-COVID-19, we will adapt again. Universities will adapt, too, as they should. If we— universities, the country, the planet— return to operating just as we did before COVID-19 came along, the pandemic will have taught us little.

***

Iqbal Pittalwala

Senior Public Information Officer, University of California, Riverside

@UCR_ScienceNews

February 22, 2021

Almost a year later we are still living surreally. Although I received my first dose of the COVID vaccine mid-February, I will socially distance and mask up — even double-mask up — for months. We will likely go back to work, in person, in the fall, and some of us are already wondering about the reverse culture shock. While I am delighted to be returning to brick and mortar, I am also concerned I am too used now to WFH. I will miss the flexible hours, the ability to attend — with Star Trek-like speeds — zoom lectures sprinkled throughout the country, the longer sleep hours, and the collapsed work-commute.

Our productivity has been high during the pandemic. Our work output may even be higher than ever. Zoom meetings are aplenty. I also attended two conferences via zoom. Both worked successfully. Human interaction, however, was missing — the kind a face-to-face encounter facilitates. It’s hard, after all, to run into someone on zoom. Serendipity is out; zoom backgrounds are in. Casual conversations are mostly out; heavily planned scripts are in.

On a local hike several weekends ago, I ran into a UC Riverside professor of geology. I had taken a break to catch my breath on my way uphill. I was enjoying the vistas the climb offered when I saw the professor jog downhill. We chatted for 45 minutes about this and that, acknowledging also how these spontaneous conversations with colleagues are now mostly stripped from our workdays. The pandemic has pushed much human interaction and contact away. Days go by when I don’t see anyone except at a distance. I can’t remember when I last hugged someone. All this will be a memory, the UCR fall quarter this year promises. We will return, slowly, to how it was pre-pandemic. Will that also be when we will say how wonderful WFH was?

***

Natalie Rogers

Communications and Outreach Specialist, The University of New Mexico

@LeiaShotFirst

Almost three years ago, I read a book by David Quammen, called Spillover, about infectious viruses that come from animals. That book, coupled with upheavals in my personal life at the time, set me on a new career path in public health. In a horribly perverse way, the COVID pandemic has solidified and validated that choice. I started a MPH program last year, and hope to transition to a public health science writing/comms career in the future.

My life feels out of balance with my brain—COVID is all I can think about, and I’ve been creating social media content on Instagram stories with information and news updates and (hopefully) easy-to-understand definitions about things like “case fatality rate” and “super-spreading events.” I’m consuming news and journal articles and Twitter feeds and regurgitating them for my friends and family online, because it helps me feel some sort of semblance of control over the situation. It’s like a train wreck: I can’t look away.

Unfortunately, it also feels like my actual job (writing about university research) and my classwork have been suffering. But I’m trying to give myself a break, as I am also homeschooling my 11-year-old while trying to work full time and attend class part time. That’s a lot! And I’m lucky: I have a supportive job with health insurance, and our governor worked fast and cases have remained low here so far.

And really, I know, none of us have control over what’s happening. All we can do is make smart choices for ourselves and hope others do the same.

***

June 2, 2020

I imagine I would be writing something a bit different had I done this update last week. While I’ve always been aware of racial inequities in this country, and COVID has certainly put healthcare disparities into stark relief, the last few days are unlike anything I’ve ever seen.

That yet another Black man was murdered on camera by white supremacy.

That Black Americans have to protest for their lives during a pandemic that ravages people who gather in large groups.

That we have a president who would gas his own citizens protesting peacefully for a photo op.

That on the nightly news and on Facebook my parents are seeing cops hugging protesters and on Twitter I’m seeing those same cops beating and tear gassing those same protesters minutes later.

That still, in 2020, too many white Americans consider property value of higher concern than Black lives.

Meanwhile COVID-19 is still ravaging communities and many states are opening up too soon, and even if they are not, now the streets are filled with either mass protests or militarized police and national guard troops.

I have to prioritize mental health, and I still have work to do for my job, but it all seems so ridiculous and pointless in the context of our country right now. I want to *do something* but aside from lending what time and money I have, there isn’t much else I can do to ease this pain and suffering. What’s worse—the people who *can* do something, the people in power, seem unable or unwilling to do something.

It’s been this bad in this country for so long and it was always going to come to this—“no justice no peace” is inevitable when rights are trampled for too long. I honestly think the country is headed for a crossroads.

***

Marla Broadfoot

Freelance Science Writer and Editor

@mvbroadfoot

April 28, 2020

I feel like I’ve experienced all the stages of some weird psychological process, uniquely suited to the pandemic. First there was disbelief, then survival, then gratitude, then resignation, then boredom. I joked to some science writer friends recently over a Zoom happy hour that we were in the pandemic slump, because none of us were able to focus, like writer’s block on a macro scale. A group of us, many of whom first met at NASW conferences many years ago, have been meeting weekly for a drink and group counseling session. The first meeting we laughed so often and so hard, it felt like the truest medicine. Moments of joy feel so much more precious now, and I collect them wherever I can—through yoga, meditation, walks in nature, quality time with my family (because there is so much of the other kind of time, us together hour after hour these days). Just as often I feel moments of frustration, anger, panic, fear, indignation.

I saw a neighbor recently at the bakery in our rural little town, and I found myself holding back the words “I told you so.” Only last month she had posted on Facebook that this was all a liberal

conspiracy. Once I might have simply said “Bless her heart,” under my breath, but

the stakes are too high these days. I worry about my daughters, 12 and 14, whose adolescence will forever be marred by a threat that they can’t see and that we don’t yet understand. I vacillate between wanting to hold them tight and fashion them some rose-colored glasses, and wanting to sit in front of my computer and contribute to the growing canon of science journalism around the virus. Instead of choosing, I do a little of both, as best I can.

***

Erika Check Hayden

Director, Science Communication Program, University of California, Santa Cruz

@Erika_Check

April 28, 2020

One of my students recently asked to report from a clinic treating patients with COVID-19. The “car clinic” was seeing patients in its parking lot. There, doctors could safely treat patients with COVID-19, including those with routine problems, without exposing others to the new coronavirus.

It was a great story. But should my student go to the clinic to report it? She was willing, but I was worried about exposing her to the illness. It was an especially difficult call since I myself had traveled to Sierra Leone to cover Ebola at the height of the epidemic in 2014.

This is one of the many challenges I’m navigating as a journalism professor amid the COVID-19 pandemic. I direct the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Our program focuses on practical experience alongside classwork, so we’ve moved our classes online and arranged for students to complete spring internships remotely. We’ve also changed our training to help local and regional media coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

That’s what brought my student, Lara Streiff, to the car clinics story. One of our spring-quarter instructors, data journalist Peter Aldhous at BuzzFeed News, revamped his class to support The Mercury News, whose audience lives at an epicenter of the pandemic in Silicon Valley. When Lara found the car clinics story, Merc science reporter Lisa Krieger was eager to run it.

But I decided I couldn’t send Lara to the clinic without dedicated safety training. She didn’t let this set her back; instead, she conducted remote interviews and found creative ways to get the details she needed. Lisa and former Merc editor Ken McLaughlin helped Lara polish the piece, which ran in the Merc—one of many COVID-19 pieces that my students have now published on vaccines, testing, treatments, and other issues. I’ve been struck by how purposefully my students are embracing the call to apply their training to covering COVID- 19. They’re finding meaning in serving communities with the reporting they need about this pandemic. Their grace and determination in taking on the tough, real challenges of science journalism gives me hope—now, and far into the future.

***

Mary Miller

Science Producer/Environmental Program Director, Exploratorium

@explomary

Oddly, the coronavirus pandemic has been a blessing for my science writing. Not that I’m writing about infectious disease—the environment and climate is more my beat—but being sheltered

at home has given me more time to do research, interview scientists, write, and produce online content. Those are all tasks that for me are better suited to working in my quiet office at home than a busy,chaotic museum. I began my career at the Exploratorium as a science writer and online media producer, but since then my duties have expanded to public program host and director for environmental science partnerships. Sadly, that means I don’t have as much opportunity to write as I’d like—I have to squeeze it in between project and program planning, team meetings, and talking to museum visitors about science. It’s a lovely job and I miss engaging with the public and seeing my colleagues in person, but present circumstances give me the luxury of time to read widely, think deeply, and write every day. I’ve even started a coronavirus journal where I keep task lists for my family and impressions of this frustrating, scary, boring, uncertain time. I haven’t kept a journal since my college days, but, like this time capsule, personal accounts might give insights to future generations just as Camus’ The Plague provides useful lessons for COVID-19.

I’ve also been looking for lessons that this global pause provides for environmental science and climate change. In the midst of all the bad economic and health news, it’s a bright spot that with less heavy industry and fewer vehicles on the road, air quality has never been better in the Bay Area and all over the world. While that might not last once the economy gets going again, maybe citizens that have enjoyed this respite of clean air will start demanding that their governments regulate and reduce air pollution and carbon emissions.

But on a more fundamental level, science itself has proven its worth through this pandemic. In the Bay Area and Sacramento, leaders listened to scientists and acted with some of the

first shelter orders in the country... and it worked. California has among the lowest per capita coronavirus cases in the country. Scientists and science writers also have a critical role to play in guiding the response to climate change before it becomes a global pandemic. This time I’ve had to reflect has left me as committed as ever to helping the public understand the climate system and communicating ways to reduce carbon emissions and improve the health of our planet.

***

Bryn Nelson

Freelance Science Writer

@SeattleBryn

April 28, 2020

This morning, I was texting with a friend who is kindly sewing masks out of repurposed surgical tray material so I can rush them to a relative being treated for cancer at the Mayo Clinic. Within minutes of our conversation, I saw photos of Vice President Mike Pence standing by a patient at the Mayo Clinic while flouting the hospital’s strict policy of not entering without a mask. It seemed like the perfect encapsulation of an absurd, sad and disturbing month. People have repurposed bandanas, vacuum filters and even trash bags to protect themselves and loved ones. Doctors and scientists are trying to devise new safeguards amid a flurry of caveats and contradictions about the best way forward. And more than a few politicians are ignoring, twisting or cherry- picking scientific data while disregarding rules and guidelines.

Everything feels urgent and blunt and insufficient. I’ve felt proud to be part of a profession that is trying to chronicle the truth and the evolving science amid a flood of misinformation and historical revisionism. But I’ve been intensely frustrated at the handwringing over whether and how to fact-check obvious lies and disinformation that could endanger public health.

I’ve known people who have fallen sick and died, and I’ve tried hard to keep my emotions in check while writing sensitivity and fairly. It’s taking a toll, but I feel lucky to still have my health, home and livelihood. I’m cooking and gardening more, and marveling at the new radish and pea sprouts in our front yard. And I know that some important messages are sticking. My niece recently wondered why her younger sister was singing “Happy Birthday” to herself in the bathroom. I realized she was taking the public health messaging about hand washing to heart, and it made me smile.

***

Science Reporter

Oregon Public Broadcasting

@ErinEARoss

April 28, 2020

The last time I talked to my grandfather, Phil Ross, was December 31. That same day, China announced that a mysterious respiratory illness was spreading in the city of Wuhan.

I mention this because, unlike many others, my coronavirus story has been about recovery. In the weeks after Phil died, I was a mess. At home, I stayed in bed. At work, I set up a global wire alert, and watched case counts climb. Before I was a science journalist, I worked in a disease ecology lab. Outbreak watching was my morbid pastime. I made simple disease models to quiet the storm in my head.

In mid-January, I went to visit my grandmother in Florida. Each night, tiny yellow alerts flitted across my laptop screen, bringing updates on the virus. Under Florida’s winter sun, the outbreak felt a world away from the silent grief of our gathered family. Then the virus came to Oregon, and I reported like my life depended on it. And as the world got worse, I got better. My hours in the lab were finally useful. For the first time in two years, I felt like I had something valuable to contribute: when the outbreak started, I was the only person in my newsroom who had ever heard of RT-PCR, let alone run one. It gave me a purpose, something to fix other than my family.

When you write about science, you live in a world of unanswered questions. Life with COVID-19 is no different. Every day we learn a little bit more about how little we know. Most people aren’t used to living with growing uncertainty, but in that eternal hunt for answers, I found solace. I got my drive back. I got better.

I still worry constantly, of course—I have an anxiety disorder. I worry about my father, who is still grieving and at high risk of COVID-19. I worry about my mother, whose social circle has shrunk to the people she passes while walking the dog. I worry about my grandmother, and the aunt who gets her groceries. I worry about my community. I worry about the Cascadia earthquake.

But the thing about those fears is they’re all based in uncertainty. And since I’m a science journalist, I know what to do with that—I poke it and prod it and ask it probing questions until something resembling an answer, no matter how unsettling, falls out.

***

Ashley Belanger

Science Writing Graduate Student, MIT

@ashleynbelanger

May 1, 2020

I joined MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing last fall, and classes end this May. In March, I was planning my Spring Break, imagining day trips I might take out around Massachusetts. Instead, Spring Break arrived early, extended to two weeks when all classes were canceled, then transitioned online. Some of my classmates left town for good. I continued working to finish my thesis and semester coursework, but I was thinking about friends and

family all over.

When my former editor at Orlando Weekly asked me to apply for a National Geographic grant for emergency funding to do COVID-19 coverage on domestic violence in Florida, I paused my graduate program work to pursue that story. I received funding in mid-April and spent two weeks reporting, while rotating through the rest of my school assignments. Productivity usually keeps me from feeling frantic, so it was easy to lean into that now. I also intern for Gastropod, which has been a real source of joy for me this whole semester, but especially since I’ve been isolating in my apartment alone, with only my dog and cat as company. Working on different episodes each week—gathering sound, researching topics, and finding sources—keeps me diving down new rabbit holes instead of scrolling Twitter. The co-hosts, Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley, joke around in the Gastropod Slack channel, which keeps things light, and sometimes I get extra lucky when Cynthia goes to a local market and drops off fresh oysters on my stoop. It’s a tiny taste of the Spring Break I wanted.

When classes end, I have three weeks off before my summer internship starts at New England Center for Investigative Reporting. I’m hoping to research and pitch an investigation to occupy the next couple of months.

***

Ashley Belanger

Knight Science Journalism Project Fellow

@ashleynbelanger

February 6, 2021

After graduating from MIT’s Science Writing program last year, I was extremely fortunate to receive a 9-month project fellowship from Knight Science Journalism, but I had no idea where to move to do that work. I knew I needed a quiet space with a yard for my dog, but my top priority was affordability. I also craved the ability to do laundry without begging cashiers for quarters (the coin shortage this summer really scarred me). I found my pandemic destination in a cottage on 75 acres of private wildlife conservation area in northern Maine, right by the Canada border. It’s been snowy the past three months, but it’s good to feel safe and more financially secure. Paying only a quarter the rent I did in Boston allows me to save while I figure out how to continue funding my work after May.

The best part of my fellowship is connecting with science journalists from varied backgrounds, with varied processes, and getting a chance to hear how they talk about their work. We gather for seminars and informal chats that have managed to do the impossible: make me look forward to launching Zoom. For my project, I’ve finally concluded the bulk of the research and am moving forward with crafting the story, and it’s never stopped feeling a little insane that through this slow-moving COVID-19 nightmare, I’ve had the gift of time to go in-depth on this project.

Right now, I’m taking a little break to serve as a judge for Knight Science Journalism’s 2021 Victor K. McElheny Award, which means I get to read a bunch of super-important local science journalism stories that people managed to pull off in the past year to serve their communities. I continue to feel lucky to be entrenched in science journalism.

***

Amy Maxmen

Senior Reporter, Nature

@amymaxmen

One of my biggest challenges is also the thing that I find gratifying: I’m writing about problems that move me. I’m incredibly lucky to do work that is relevant right now. The flip side, however, is that response to COVID-19. I wake up thinking about these problems, and where the outbreak is headed, and what it means for our world. When I talk with my family and friends, I too often end up ranting about these issues. When I try to escape for a walk, podcasts generally fail to drown out my thoughts.

Another challenge is pettier, but I’ll list it for the sake of honesty. Because I’m writing about news that I feel matters, I want to write in-depth stories that readers respond to and share. That’s not always possible because of my own failings as a writer and the constraints of writing for a single trade publication. At times, I feel envious of other writers. But that said, I far prefer a slight jolt of envy because of a great piece, to the despair I feel when media outlets write damaging stories. (No more model nonsense, please!)

***

Ellen Kuwana

Freelance Writer/Editor

@EllenKuwana

May 3, 2020

My workload has shifted significantly this past month. When Seattle became the epicenter, I decided to send a thank-you meal to the University of Washington Virology Division, who were processing COVID-19 tests 24/7. Restaurants were closing near the lab, so what started as a gesture of appreciation morphed into a lifeline of meals. I continued to coordinate meals and work two jobs, but quit my main job April 10 to devote more time to this volunteer effort. More places contacted

me to ask for help getting meals for their frontline employees. This is how www.WeGotThisSeattle.co got started.

I feel as if I’ve trained for this my whole life! Lab skills such as familiarity with protective gear and being aware of what I have touched give me confidence that I can pick up and deliver food safely. Twitter has been essential: it’s such a great way to get information quickly. It’s the main way I communicate and thank restaurants that donate or discount food. My third tweet about Taste of India’s donated dinner to UW Virology got 31,000 likes. It resonated, I think, because we all want to help in some way, even though many don’t know exactly how to right now.

I’m finding joy in helping people. The thank you notes and photos keep me going. It’s amazing how close I feel to people I didn’t know before—they are deeply grateful, and no one has time

for fake conversations or small talk. People are dealing with life and death. Restaurants are trying to stay afloat and keep staff employed—it’s a tough time. Workers are tired. Food is a much-needed morale boost.

In April 2020, our small volunteer team fed more than 6,500 frontline workers at 40 sites, all funded by individual donations. Donations are tax deductible.

***

Ellen Kuwana

Freelance Writer/Editor

@EllenKuwana

February 5, 2021

I woke up braced to feel crappy. I was tired, but that’s normal as a working mom with a pandemic puppy that wants to go outside at 1, 3, and 6 a.m. My upper arm was sore, which I expected in response to the COVID-19 vaccine, and I was tired and had a headache. But no chills, no fever. Hmm, not so bad.

On February 4, 2021, I became one of the 8% of people in the U.S. who have been fully vaccinated for COVID-19. I’m not a frontline worker. But starting last March, as the novel coronavirus was spreading through the Seattle area, I launched a volunteer effort to feed my city’s frontline workers.

While picking up hundreds of deliveries of food and getting them to healthcare sites, I’ve had to get used to some level of risk of exposure to COVID-19. My husband works in a hospital, though, so really, was I safe just sitting at home? I might have made a different decision if my husband could work from home, but with the very real possibility of him bringing coronavirus into our home, I decided taking some risk was worth it to me to be able to help others during this pandemic.

My posts to Twitter about WeGotThisSeattle.org caught the attention of a Seattle podcaster, who invited me onto her show. It turns out we live in the same neighborhood and we’ve stayed in touch and become friends. In early January, she contacted me to ask if I knew of any resources for the vaccine hesitant. I responded with, “I can’t understand that at all—I’d love to get the vaccine.” She urged me to put my name on our county’s vaccine waitlist. Being the writer I am, I wrote an overly long email explaining my volunteer effort and prefaced it, “Please add me wherever is appropriate on the list.” I didn’t want to jump the line.

In the email, I explained that since mid-March, I’d fundraised almost $100,000 (purchasing goods from local restaurants) and fed or caffeinated nearly 23,000 frontline workers in Seattle. Future plans include getting meals to psychiatry staff in a prison, feeding staff and families at Ronald McDonald House, and delivering hot meals to all 3,400 King County Metro bus drivers. I explained that while I try not to go inside the sites where I’m delivering food, sometimes I have to. Despite careful planning and safety protocols, deliveries rarely go smoothly.

My scariest experience happened right after I delivered breakfast to a nurse, Regina, at a large urgent care facility. Some weeks I see her two or three times a week. I now consider her a friend. I was the returning to my car after she went inside with a cart piled with food and coffee. I was the only person outside when a car pulled up in front of the ambulance bay. I turned around to say, “You can’t park there,” when the driver opened the door and fell out onto the concrete. Feeling like I was in a movie, I ran inside to get help. Regina turned around and sprinted outside. Realizing that the driver hadn’t been wearing a mask, I grabbed one from the box near the door and raced back outside to put it on the unconscious man in the driveway. My only thought was protecting my friend. My heart was racing. What if he had COVID?

Two minutes after sending my email, I had a reply. Anyone supporting frontline workers is considered essential, the reply read. A site 40 minutes away from my home had enough doses. Call this number, make an appointment, bring the attached authorization form and a photo ID, the instructions read.

My teenage daughter accompanied me in the car for both shots, which made me feel more at ease about driving home, just in case I had any adverse reactions. For the first shot, it was clear to me that I was surrounded by healthcare workers getting their shots. This time, there were many older people from the general public. I was happy to see that the lines were longer, three weeks after my first shot. I smiled at everyone, hoping they could perceive my thankfulness behind my two masks.

What I will remember from these past 11 months are the tired faces of nurses, respiratory therapists, mortuary staff, and others. People have cried when I deliver food to them. I am glad I didn’t choose to stay home. Yes, my anxiety level might have been lower, but it’s been an honor to care for those who are caring for others—even in a small way. We’ve been sprinting a marathon, and everyone is exhausted. Availability of the vaccine has given all of these workers a much-needed boost.

I feel so grateful to have gotten both shots now. I was sort of hoping to feel bad so I could give myself permissions to laze in bed for a day and watch TV. But as has been true since March, there is still so much to do. Now, though, I can deliver food with less worry for my own safety.

***

Calley Jones

Ph.D. Student, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Clinic

@CalleyJSciWri

May 5, 2020

The last time I graduated and moved across the country to start a new phase of my career, it triggered a depressive episode that defined my first two years of graduate school. That certainly doesn’t make me unique. Massive life changes frequently trigger episodes of mental illness, even in people who have never struggled with mental illness before. No, hitting rock bottom after transitioning to graduate school doesn’t make me unique—what it makes me is cautious.

I plan to graduate with my doctorate in August, so the fear of another impending life transition began mounting even before COVID-19 reached Minnesota. Would I apply for fall internships? Where would I have to move? Where would I end up after? Was I making enough networking connections? Would I have to leave all my friends again and uproot the life I made here? Should I be trying to write and pitch stories? Would time spent on career development take away from research and delay my graduation?

Those questions didn’t go away when COVID-19 came, but new questions began piling on top. With limited lab time, can I still graduate at the end of summer? Are fall internships going to be offered? If I’m not writing COVID-19 stories right now, am I killing my career before it even starts? Will my family make it to my defense?

If hitting rock bottom during my last life transition made me cautious, staring down the next one during a global crisis makes me downright afraid. I cannot answer the questions swirling in my mind if I’m not well enough—physically and mentally—to approach them. But how do I manage to stay well with so much at stake? I choose to trust that the balance exists, even if I’m still struggling to find it.

***

June 9, 2020

I feel that people will look back on 2020 as the year of one thing after another, after another, after another.

There are already plenty of memes on this subject, to the tune of “Coronavirus wasn’t enough— let’s add murder hornets!” and “NASA confirmed the existence of UFOs and it was barely newsworthy!” It’s almost comical, in the way that “you have to laugh or you’ll cry.” I have laughed at these memes.

I have also cried over the weight of everything.

I have a close friend, who lives in another state, whose mental health has taken a serious hit as a result of COVID-19. I had trouble contacting her this weekend, and it scared me. It was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. I broke down on the phone with my dad, sobbing because it was all too much. My forehead pressed against the wall, tears dripping down the paint, I said:

“I can’t care about my friend and care about racial inequality and care about COVID-19 and care about my own personal health and care about defending my thesis and care about applying for internships and care about what happens if I don’t find a job. There’s only so much of me. There’s only one Calley. It’s too much to feel so deeply about all of it.”

Humans can do incredible things when stretched to their limits. There’s been a lot of stretching lately— a lot of room for personal growth in a short span of time. Still, it takes a toll. It can be overwhelming. It can be too much.

I think that’s how I’ll end up remembering 2020— the year that was too much.

***

Helen Santoro

Freelance Science Writer

https://twitter.com/helenwsantoro

June 2, 2020

So much has changed this spring. My wife lost her job as a UX Director due to COVID-19 budget cuts, so finances are far less steady than they were before, and I’m focusing on moving from my position as an editorial fellow at High Country News to a full-time freelancer. It’s truly a time of transition.

Changing careers while tons of journalists are being laid off or furloughed is scary. While I’m learning how to pitch efficiently and developing relationships with editors, some outlets have frozen their freelance budgets, and others are completely overwhelmed. To say the least, it’s a tough time to make a go of it as a freelancer.

Although nerve-wracking, this transition has helped me realize where I want to focus my efforts as a journalist. My interest in medicine and mental health, in particular, has really come in handy. I feel like there is no better time to use our skills as science journalists to break down scientific misconceptions and show the public why science and research are so vital.

I’ve found such support through members of NASW and the new Science Writers Association of the Rocky Mountains, formed by the wonderful Alex Witze. Also, as a graduate of the

UC Santa Cruz Science Communication program, I feel like there is always someone I can turn to for advice. I feel lucky, especially now, to be part of such a supportive, collaborative community.

***

Helen Santoro

Freelance Journalist

twitter.com/helenwsantoro

February 21, 2021

My energy and confidence in myself as a writer comes and goes in waves. Some days I'm busy with work or really engaged in a piece that I'm passionate about and feel like everything is going well. And then the next day I'll wake up and wonder what I'm doing, or if this freelance career is stable enough to support myself, my wife, and our four fur babies (my wife lost her job last April due to COVID). Just last week, for example, an editor that I work with semi-regularly emailed me saying she has COVID and will be out for the next few weeks. It's those types of things that really knock the wind out of you because you never want to see a fellow journalist struggle, and it makes the already rocky world of freelance even rockier. When will the edits come in? Do I have enough checks coming in this month to pay the bills? Will I make my income goals this year? All of these questions are always there for a freelancer, but with the pandemic, they seem even more prevalent.

***

Jonathan Wosen

Biotech Reporter, San Diego Union-Tribune

@JonathanWosen

June 2, 2020

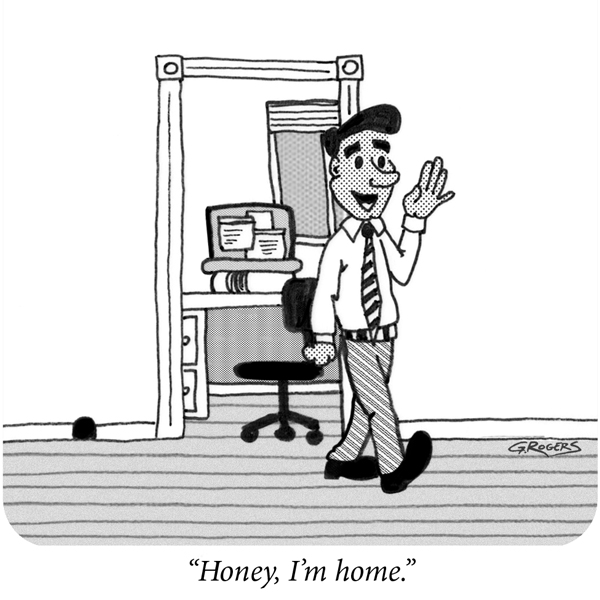

I’m less than two months into my job as the biotech reporter for The San Diego Union-Tribune. This was (and still is) my dream job. After all, I get to cover biomedical science for my hometown paper. But what a time to start a new job! I’ve been working remotely and communicating with editors, fellow reporters and sources via email, Slack and Zoom. I’ve never seen what our newsroom looked like under normal circumstances, and it’s starting to look like I never will. Even after COVID-19, our editors have talked about encouraging people to work from home about half the week and minimizing the number of people in the office at any given time.

I’ve felt extra pressure to hit the ground running, but nearly all that pressure is self-inflicted.

My editors and colleagues have been extremely supportive and understanding. Covering the pandemic has been stressful and disorienting at times, but it feels good to be working alongside so many other skilled journalists to help the public keep track of everything that’s going on. Some of the added pressure I feel comes from a sense that readers are making decisions about whether to social distance, wear facial coverings and take other protective measures based on what I write. The Union-Tribune has more readers (and subscribers) than ever before, but our advertising revenue has tanked because local businesses that are closed don’t have any services to advertise. We’re all taking a 10% pay cut at the paper, and most of us are taking a half-day of furlough each week. I’m not too worried, though. I’m just grateful to have a job right now.

***

Clinton Parks

Freelance Writer

@crparks3

The set of circumstances we now find ourselves in are strange and scary. I’m still officially a freelance science writer but since last September I’ve been a contractor with National Geographic doing web production and editing. I worked at its downtown office in D.C. working regular hours. I still was doing freelance writing projects for a few clients. However, with the onset of the COVID pandemic and subsequent quarantine, my situation quickly changed. I and my National Geographic colleagues were told to begin working from home. Then

my freelance clients had to understandably cut back their budgets, meaning that work dried up. Still, I have been one of the fortunate ones. My wife and I are healthy with a house, income, and food. My biggest adjustment to actual work has been getting a desk and a second monitor.

But during all of this a lot of my focus has been on the outside, specifically my Black brothers and sisters. The situation was bad enough with the spreading of the virus highlighting the health disparities among White folk and people of color. As a purposeful underclass, my people are overwhelming tasked with the essential jobs necessary to keep this capitalistic system humming. And they largely do not have the resources or access to the health facilities to adequately combat this virus. As if this were not enough to remind us of how our nation and many of our fellow citizens see us, the extrajudicial executions of Black people during this time of worldwide crisis drove the message home. But at last, perhaps with the nation mostly home and watching, they could not turn away. Perhaps we’ve finally hit the breaking point, or perhaps it’ll be just another blip in our long history of disappointment.

***

Clinton Parks

Content Specialist (Freelancer), National Geographic Society

@crparks3

February 16, 2021

So much has happened since my last remarks. It's reminiscent of that sci-fi trope when someone is in a coma for a short time during which an extraterrestrial civilization has conquered Earth. Like everyone else, the isolation necessitated by the pandemic has been wearing. Seeing the mistreatment of Black and other fellow people of color has been disheartening, but not surprising. U.S. politics has been disappointing. (What good are laws when they don't apply to the most complicit of violators?)

In that time, I was brought on full time at National Geographic Society with the Education Department. There, I had recently started a program to help fill in some of the gaps in the U.S. educational system regarding institutional racism, science, and history. I was still doing some freelance writing. I was playing tennis and writing my second novel. I was also preparing to co-lead an NASW panel discussion with Jeff Perkel.

My life was full, fulfilling, and changing.

In late July, I came down with what I thought was bad food poisoning. I'd had that happen before about 15 years ago, which kept me up all night but was over within a day. But this time, the symptoms lasted several days after. And then my abdomen started cramping to the point of doubling over with crippling pain. Worse, I was having trouble relieving myself. After several attempts at home remedies and a couple visits to the clinic, it was recommended I visit the emergency room. After a 15-hour wait, I was checked in. Nine days later, I left the hospital after abdominal surgery and a stage-3 cancer diagnosis.

I took a leave of absence from work and began distracting myself with books, videos, and video games. Family, friends, and work colleagues were amazing in the support they showed to me and my wife during this tough time through advice, food, dog care, and general kindness.

I'm writing now after recently having completed my chemotherapy treatment, including infusion and pills. I lost some weight (some of which I don't want back) and some strength (which I do). I've since returned to work, but not nearly the level of activity I'd had before my diagnosis.

But I'm alive. Nothing makes you cling to life more than the prospect of its absence.

***

David Malakoff

Deputy News Editor, Science (Policy, Energy and Environment), Science/AAAS

@DavidMalakoff

June 10, 2020

As the pandemic descended, I felt a bit like a guy who sees the light at the end of a tunnel—but suspects it’s a train. At Science, which is fortunate to have a corps of journalists with more than a century’s experience covering infectious disease, we published our first coronavirus story, from China, on January 3. Over the next month, I teetered between trying not to be overly alarmist—in either the stories I handled, or my personal life—but also prepared. I had reported on pandemic planning war games, and the 2009 H1N1 outbreak, and understood the gravity. By mid-February, my family was stockpiling non-perishable food (a run on toilet paper hadn’t come up in war games), to the amusement of some friends. As I watched early data come in showing an increased risk for the elderly—like my 93-year-old mom—and older people with asthma —like me, at 58—my concerns became more personal. In late February, I quit my ice hockey team; small locker rooms were no place to be. I quit my whitewater kayaking group and its carpools. I put my will, life insurance, and financial records in order.

By March 9, I was working from home, and soon all my colleagues were too. My professional life became a blur of 8-, 10-, 12-hour days, working with a remarkable group of staff reporters, editors and freelancers. Stories arrived from around the world, at all hours. Science’s readership exploded, breaking records by the millions. On March 31, I wrote a story that began with a line that reflected my sadness, anger, frustration and fear: “America is first, and not in a good way.” My country led the world in reported infections. It seemed we had made every mistake ever identified by pandemic planners. And it was far from over.

***

Gina Mantica

AAAS Mass Media Fellow, Dallas Morning News

@gina_mantica

June 20, 2020

As a graduate student I’m used to working on my own. During this academic year I actually spent most of my time with birds rather than people. So I surprised myself when I started feeling lonely in isolation. I’ve spent the past few weeks working for The Dallas Morning News from the dining room table in my small Massachusetts apartment. Despite the multitude of Zoom check-ins and phone calls I now have, the loneliness creeps in. I miss face-to-face interactions—getting to see someone in their entirety, read their body language and high five or hug. I’m really looking forward to spending time with the people I love, once it is safe to do so.

I’m also grateful that my graduate school training prepared me for working independently this summer. I can manage my time and stay organized, even in my home “office.” Though distractions are ever present when working from my dining room, I know to push through until after the work is done. The distractions aren’t going anywhere, anytime soon.

***

David Levine

Independent Journalist

@Dlloydlevine

August 20, 2020

I live in New York City. We went on lockdown on March 16. Restaurants, gyms, Broadway, museums and movies were all closed. Most are still closed. I had not planned on going anywhere because my daughter was due on March 22 . She gave birth to a baby boy, Gabriel, on March 6. That was fortunate as under lockdown her husband would not have been able to be in the delivery room.

I have read many accounts of people who have been isolated by choice or by circumstance. Ann Frank's father insisted that the children make their beds every day and study. In other words, have a schedule.

Under lockdown we were only allowed to go to the pharmacy, grocery store and go for a walk. I needed to find something to focus my mind. And I did.

As co-chair of Science Writers in New York, One of my roles was to interview authors in person before an audience. I could not do that now. In discussion with my co-chair Joe Bonner, who became my producer for the talks, we decided to do them on Zoom and not only interview authors but also journalists and healthcare experts on COVID-19. We had a good audience for the talks and were able to record them and upload them to our YouTube Channel.

Among the journalists I interviewed were Carl Zimmer, Roxanne Khamsi, Gideon Gil, Ivan Oransky and Malin Attefal, a Swedish TV journalist. I also interviewed vaccine expert Paul Offit, Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist with Johns Hopkins, Helen Fisher on dating during Covid-19 and psychologist Jeffrey Cohen on coping with isolation. Among the authors I interviewed were Maria Konnikova, Susan Schneider, Doug Levy, Lisa Selin Davis and Pam Fessler. You can see them all at https://www.youtube.com/user/ScienceWritersNYC

***

David Levine

Independent Journalist

@Dlloydlevine

February , 2020

I live in New York City. This summer was great as the COVID-19 rates in Manhattan were below 2%. Although I have not taken a subway yet, I do take buses. And I discovered New York City has a wonderful ferry system. You can talk ferries to Wall Street, Far Rockaway Beach and Sandy Hook on the Jersey Shore.

With SWINY co-chair Joe Bonner, my producer for the talks, we continued our interviews with authors, journalists and healthcare experts on COVID-19. We had a good audience for the talks and were able to record them and upload them to our YouTube Channel. We applied for and received a Peggy Girshman Idea Grant so we could make the interviews more professional. The money will allow us to buy a better camera and microphone.

I had the honor of interviewing for a second time vaccine expert, Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. In addition, I interviewed Dr. John Moore, professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College; Dr. Amit Kumar, chairman, president, and chief executive officer of Anixa Biosciences; Dr. Dominique Brossard, professor and chair in the Department of Life Sciences Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Robert Klitzman, MD, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeon.

Among the journalists I interviewed were Apoorva Mandavilli, Gerald Posner, Carl Zimmer, Jon Cohen and Ed Silverman. I also interviewed a panel of journalists from Latin America; Estrella Burgos Ruiz Myriam Vidal Valero and Fabiola Torres and from Europe Malin Attefall (Sweden), Yves Sciama (France), and Eva Wolfangel (Germany).

I interviewed several authors including George Zaidan, author of Ingredients: The Strange Chemistry of What We Put in Us and on Us; Jessica Wapner, author of Wall Disease: The Psychological Toll of Living Up Against a Border; and Cheryl Pellerin, author of Healing with Cannabis: The Evolution of the Endocannabinoid System. In March, I will be interviewing Carl Zimmer on his new book Life’s Edge: The Search for What it Means to be Alive and Sherry Turkle on her new book The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir.

And we also had a virtual happy hour with Science Writers of the Upper Midwest (SWUM).

You can watch the interviews at [https://www.youtube.com/user/ScienceWritersNYC](https://www.youtube.com/user/ScienceWritersNYC)

***

Theresa Machemer

Freelance journalist

August 20, 2020

Today, I’m having a bad day.

On bad days, positive messages can feel isolating. Journalists are more important than ever, science communication is more important than ever…I know this is true. But why can’t I think of any new stories? I feel guilty that I’m not doing enough to help. I see the messages about self-care and allowing yourself to produce less without feeling bad about it. But as a freelancer, my income is linked directly to my output as a writer. If I don’t have the financial flexibility to give myself a break, I wonder, have I not been working hard enough before now? Did I not negotiate, or have I already been doing less than usual? And now the guilt is multiplied. On bad days, I begin think that maybe I wasn’t cut out for this. I’ve kept up with my anchor gig, but I’ve let other projects slide. I wish I could do more. I find joy outside of work. I play with my cats. I started working on a novel. I’m painting maple leaves on a portion of my office wall with some of the paint samples left over from when my fiancé and I first moved into this apartment.

There are good days, too, of course. I work with great editors every day. But bad days happen, and I can’t be the only one dealing with them...right?

***

Leah Rosenbaum

Healthcare reporter, Forbes Media, LLC

February 11, 2021

One of the most difficult parts of the pandemic is how inescapable it has been. Not only am I writing about COVID-19 daily, but as the "go-to expert" in their lives I have become a source of information for my family and friends. My grandparents call to ask whether they should get the vaccine; my parents want to hear about the new variants over zoom; my friends are asking me over text if they should postpone their weddings or not. I try to help them the best I can (and let them know that I'm not actually an expert, just someone who reads a lot about it), but I desperately want to talk about something, anything besides the virus. But no one is doing anything, so there's nothing else to talk about. Nothing else has impacted all of our lives so fundamentally. I answer the questions that I can, all the while feeling imprisoned by the virus in more ways than one. It consumes my work days, and it consumes my downtime. So if you happen to know anyone who wants to talk about baking, or global warming, or even politics, I'm free.

***

Kendall Powell

Freelance science writer

March 19, 2021

One year plus one week ago our kids were sent home from school for the pandemic. We were lucky. My spouse and I could work from home, we had Internet that mostly handled four of us streaming, and my freelance work held steady. My home office is a loft space above our open-plan main floor. It’s always been a great space—until it wasn’t.

We are still lucky compared to others who are grieving, unemployed, isolated or just full of the despair and anxiety that so often rears up on us this year. I’m sending out more local donations than ever and our neighborhood network has doubled deliveries to the food bank.

But having at least one co-worker with me nearly every day—sometimes very needy co-workers—exhausts me. Normally, I fight the isolation of freelancing with frequent lunch dates, happy hours with friends, or a stint at my local coffee shop whenever drafting.

These I miss the most. Somehow, even though I already worked from home, the pandemic has taken away a large part of the freedom that comes with freelancing. And that is the part I cherish.

Next week is Spring Break and I’m dreading it. No travel plans, of course, so it will just be me, my husband, my 9 year-old son, and my 13-year-old daughter. All in the same space. Yet again. The good news is that after the break, both kids will go to in-person school four days a week, Tuesday-Friday. For me, this is finally the light at the end of the tunnel. I can feel the day coming when I rule the house in my yoga pants and Oofos clogs (because mid-40’s) all by myself again.

I love my family, but I wish they would just get the hell out of my office.

***

Jyoti S. Madhusoodanan

Freelance journalist

May 7, 2021

Before this phase, May 2020 felt tough. I couldn't send flowers -- we knew too little about surface transmission then. My parents had been masking and distancing since early March. Flowers weren't worth the risk. Now, it's been 17 months since we met. I feel every one of the 7600 miles between here and there.

Here, my daughter looks up at a plane and says, “I’ve forgotten what it feels like to be on a flight.” “This year,” I reply. We dream of vacations. There, COVID rips through India and the borders are closed. There are no flights home. I wonder how crowded the streets will be when we visit next.

In the last 24 hours, I've (1) heard about a college acquaintance’s death (2) talked with a friend whose mother is in the hospital (3) forwarded leads on oxygen cylinders and hospitals for three people in different cities--not knowing if any of these hours-old tips will still prove helpful (4) read lab reports for my parents, recovering from COVID at home (5) filed a feature about trendy technologies (6) talked to sources about winemaking (7) pitched another story (8) considered traveling to conferences (9) sent emails that began "Happy Friday!"

This dissonance is far worse for other Indian journalists. And it doesn’t capture the last few weeks. Those included deaths in my family, delayed cancer treatments, the first time I've told a source: "I'm sorry, I can't talk now". That was when my parents tested positive. This list doesn't capture the several days my phone dies because of the calls and texts between 6 and 9 am, before I start work. In May 2021, at least there is this: (10) ordered flowers that will reach my mother this weekend.

***

Read more insights and news for the craft and career of science writing in our Summer/Fall 2020 issue. Not yet a member of NASW? Join today for a special discount.