This student story was published as part of the 2023 NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring Program organized by the NASW Education Committee, providing science journalism practice and experience for undergraduate and graduate students.

Story by Mahathi Ramaswamy

Mentored and edited by Ranjini Raghunath

Do you avoid some foods like the plague? New research published in Nature shows that this might be your immune system’s doing.

Two independent studies from Yale University and the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) report that immune cells called mast cells help mice steer clear of allergens — substances that can cause allergies. Antibodies known as Immunoglobulin E (IgE) recognize allergens and activate mast cells, which sets off alarm bells that warn mice not to eat harmful food.

“[Mast cells and IgE] have a bad reputation,” says Esther Florsheim, co-first author of one of the papers and a former postdoctoral fellow at Yale. Although they have persisted in animals for millions of years, mast cells are mostly known for their negative role in bringing about severe, and often life-threatening allergic reactions.

Their newly discovered function proves that there’s more to the story, says Florsheim, now an assistant professor at Arizona State University. Thomas Plum, a senior researcher at DKFZ and co-author of the other study, thinks that mast cells may have provided a strong evolutionary benefit to human ancestors who did not always have access to clean food.

The findings might bring scientists closer to answering a long-standing question — why do allergies exist?

Experts have debated two possible answers, says Plum. The first is that allergies are simply overreactions by the immune system to protect against parasites. “The other,” he adds, “is the idea that allergies are per se not negative, but are actually a defense mechanism themselves.”

This defense can manifest either as attempts to get rid of toxins, including sneezing and vomiting, or as avoidance of them altogether. Earlier experiments have shown that mice avoid certain allergens, but the mechanism driving this behavior was previously unclear.

To investigate this mechanism, both research groups adapted similar protocols. Mice are known to prefer sweetened water over plain water. Scientists use this preference as a baseline for measuring changes in drinking behavior.

The teams made test mice sensitive to allergic reactions by injecting them directly with ovalbumin, an allergen present in egg white. When given a choice between plain water and sweetened water containing egg white, control mice preferred the latter. Test mice, on the other hand, gave the egg white water a wide berth.

Avoiding the allergen, Plum and his team found, protected the test mice from developing symptoms of food allergy and inflammation in the gut.

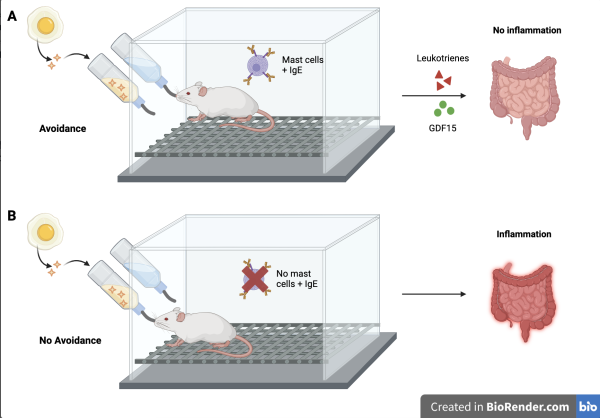

Both research groups then repeated the choice test after manipulating different parts of the immune system. Notably, test mice without mast cells or IgE lost their aversion to egg white water and continued to drink it, unlike their counterparts with intact immune systems.

In fact, the team at Yale found that test mice with mast cells persisted in avoiding the allergen for nearly a year afterwards. Florsheim suggests that this enduring “memory” could be due to the long lifespan of IgE and mast cells.

Mast cells are necessary for allergen avoidance.

A. Test mice with mast cells and IgE avoid water containing ovalbumin, and are

protected from symptoms of food allergy.

B. Test mice without mast cells and IgE fail to avoid allergens and develop food

allergy and inflammation.

Credit: Image created using BioRender.com by Mahathi Ramaswamy

Mast cells are necessary for allergen avoidance.

A. Test mice with mast cells and IgE avoid water containing ovalbumin, and are

protected from symptoms of food allergy.

B. Test mice without mast cells and IgE fail to avoid allergens and develop food

allergy and inflammation.

Credit: Image created using BioRender.com by Mahathi Ramaswamy

Allergic responses may persist for a lifetime but can develop very fast, sometimes within minutes or seconds. The researchers noticed that some test mice began to avoid egg white water after just a few sips, prompting them to ask: What rapid response does mast cell activation trigger?

They first looked at the “usual suspects”, as Florsheim puts it, behind allergic symptoms — ready-made chemicals that mast cells keep in reserve, like histamine or serotonin. The vagus nerve, which sends signals from the gut to the brain, seemed like another likely player.

Surprisingly, blocking either of these targets did not change the mice’s avoidance behavior.

Instead, allergen avoidance in the first 24 hours seemed to depend on leukotrienes, molecules that can send signals to the brain, which are produced by mast cells minutes after activation. The Yale study also found that a hormone released by the intestines, called Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15), was important for avoidance behavior after the first day.

More work is required to understand if and how these two pathways interact, and if there are other pathways involved.

“It would be interesting to look at spinal cord neurons,” Plum says, “particularly since there is a subset of neurons that expresses leukotriene receptor[s].”

For Florsheim, the future is all about mast cells. Her lab will explore other functions that might explain why mast cells continue to persist over generations. “They live there in the gut, since before you were born,” she says, “and they will be there for the rest of your life.”

Mahathi Ramaswamy is a science writer based in Marlborough, Massachusetts. She has a PhD in Neuroscience from the National University of Singapore and has worked for Khan Academy India to create educational content for young learners. She also writes about science for her website, Reading the Science. Find her on LinkedIn or email her at mahathir29@gmail.com.

The NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring program is named for longtime science writer and past NASW President David Perlman. Dave, who died in 2020 at the age of 101 only three years after his retirement from the San Francisco Chronicle, was a mentor to countless members of the science writing community and always made time for kind and supportive words, especially for early career writers. Contact NASW Education Committee Co-Chairs Czerne Reid and Ashley Yeager and Perlman Program Coordinator Courtney Gorman at mentor@nasw.org. Thank you to the many NASW member volunteers who spearhead our #SciWriStudent programming year after year.

Founded in 1934 with a mission to fight for the free flow of science news, NASW is an organization of ~ 2,600 professional journalists, authors, editors, producers, public information officers, students and people who write and produce material intended to inform the public about science, health, engineering, and technology. To learn more, visit www.nasw.org