By Amber Carlson. Mentored and edited by Laura Dattaro.

Over a year after the 2020 presidential election, the "Big Lie" — the widely debunked idea that Joe Biden won through rampant voter fraud — remains a force in American politics. As of June 2021, nearly a third of Americans still doubted Biden’s legitimate win.

But scientists are learning more about how the ‘Big Lie,’ anti-vaccine movements and other disinformation campaigns become so popular, and it’s not just because high-profile political figures have been endlessly repeating false statements. In fact, new studies are finding that some of the biggest promoters of disinformation are not political elites or influencers, but ordinary people navigating their online communities.

“Many participants in a disinformation campaign actually are unwitting agents,” said Kate Starbird of the University of Washington in a Feb. 19 session at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting. “They’re unaware that the information they’re spreading is false. And they’re unaware of their role in the larger campaign.”

Arizona voters in the 2020 election, for example, began expressing concerns online about their paper ballots being invalidated because they had been given Sharpie pens to fill them out — even though election officials had clarified the ballots were designed for use with Sharpies.

Shortly after the election, people took to social media to share photos and videos that they claimed provided evidence of Sharpie-related fraud, although these were later shown to be misleading. Even so, Starbird noted, what started out as genuine confusion and concern quickly escalated into accusations that bad actors were deliberately disenfranchising conservative voters.

Then-president Donald Trump, who had spent months sowing doubt over the election’s integrity and softening the ground for claims of voter fraud, had encouraged his supporters to look for evidence of foul play, Starbird said. But although powerful right-wing influencers had a hand in causing “SharpieGate” to go viral, Starbird said voters felt a “collective experience of being cheated” that led to them spreading the false accusations.

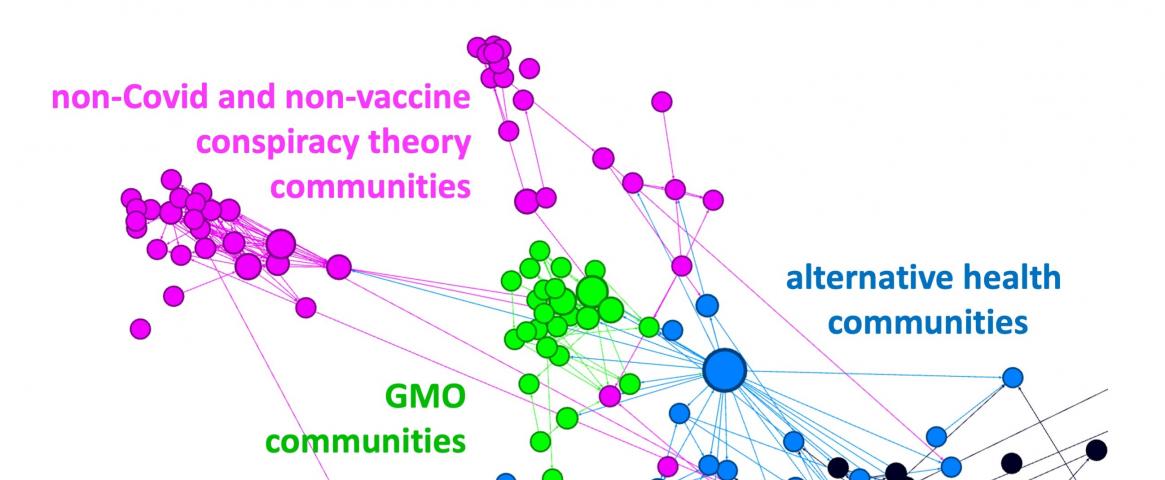

To conceptualize how disinformation travels through social media spaces, researchers have mapped out the ideologies of online users and communities and how they are arranged in vast social networks. More closely connected people and groups share more information and messaging with each other — regardless of whether that information is accurate.

Neil Johnson of George Washington University, who has been studying anti-vaccine sentiments during the pandemic, said in a Feb. 18 talk at the AAAS annual meeting that, while pro-vaccine communities are much larger in number and total users, anti-vaccine groups have had an outsized influence because of how they’re interconnected with other communities and people in cyberspace.

“[Anti-vaccine groups] are not only strongly interconnected with each other, but they’re strongly connected with the parenting communities and the pet communities, with the organic food community, with the alternative health communities,” Johnson said. By virtue of these social connections, anti-vaccine messaging has made its way into a myriad of mainstream hobby and interest groups.

Understanding how and why disinformation campaigns work could provide the keys to stopping their spread. Johnson’s research has shown that interactions between pro- and anti-vaccine communities can sometimes soften anti-vaccine sentiments.

New and improved messaging also needs to be aimed at the mainstream communities that have become hubs of disinformation, Johnson said. The “same CDC ads that go almost exclusively to [anti-vaccine] communities should go to mainstream communities focused around parenting, foods, hobbies, etc. even if they haven’t discussed vaccines,” Johnson wrote in an email.

Social media users should be mindful of what they share to avoid becoming “unwitting agents” in promoting false information, Starbird wrote in an email. Disinformation is often designed to trigger users emotionally, she added, which can cause them to share it on a whim.

Because individuals can be more susceptible to misinformation than they realize, gently and empathetically correcting false information can also help, Starbird said.

“Disinformation is often built around a true or plausible core,” she said in her talk. “Effective disinformation isn’t necessarily false, but rather, it’s misleading.”

Amber Carlson is in her first year of the MA in Journalism program at the University of Colorado Boulder. She’s currently an intern reporter with the Colorado Times Recorder as well as an editor for The Bold, a student-run publication at her university. She has a B.A. in psychology and years of experience as a professional writer. Contact her by email at acarlson@colorado.edu or on Twitter at @aecwrites. You can also view her Muck Rack portfolio at https://muckrack.com/amber-carlson.

Image: This Facebook map shows where mainstream parenting communities are getting most of their health guidance on COVID-19. Each node represents a Facebook page. According to Neil Johnson's research, alternative health communities help connect mainstream parenting communities with groups that promote non-COVID-related conspiracy theories. Graphic credit: Neil Johnson