By Lillian Eden

A field trial to test the mettle of American elms in cities has entered its first growing season, the culmination of decades of research with the goal of restoring elms to urban spaces and forests across the United States.

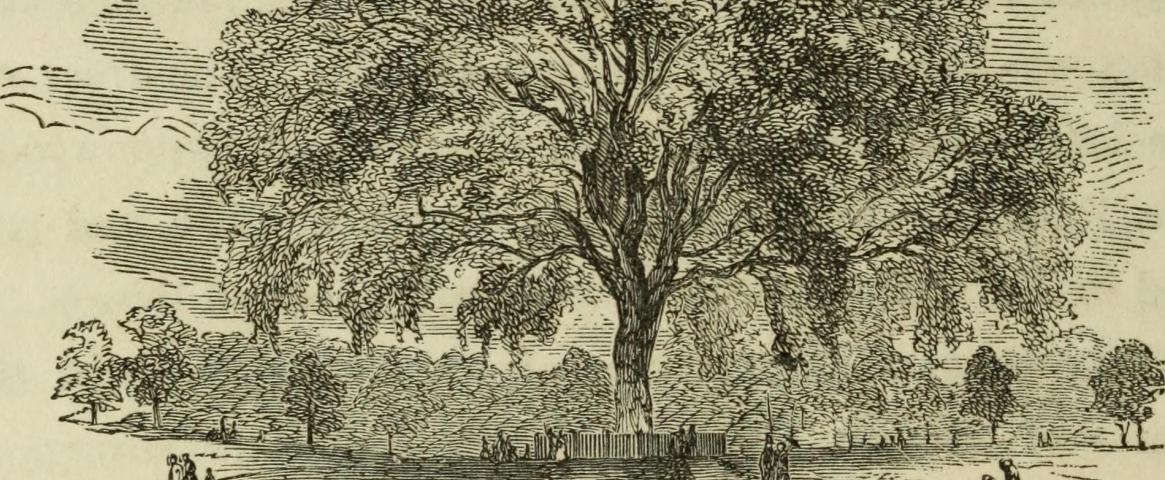

American elms were once the most widespread urban tree in the United States, providing deep shade and cooling due to their lofty heights and dense canopy. In the 1930s, they began wilting and yellowing because of Dutch elm disease. DED is caused by fungus carried by native and invasive elm bark beetles, which burrow into the bark of trees both living and dead, spreading the disease.

Some trees survived, so, over the years, scientists cloned those trees, and tested and crossed those clones in an effort to create a genetically diverse population of elms. The trees have already been reintroduced to their natural forest habitat, but elms have never been tested like this in cities.

“I would say the level of resistance we’ve achieved is probably sufficient to help restore the species in the wild. We’re not so sure if it’s sufficient for the urban environment yet,” said Christian Marks, an ecology and conservation researcher associated with the project who works on floodplain forest research, where elms hail from, for the environmental nonprofit The Nature Conservancy.

Elms are fast growing and native, providing both an expansive cooling shade and connecting city streets to a larger ecosystem, benefits that are not easily replicated. Nonnative species of elm don’t grow as large or don’t have as dense of a canopy, and are not as palatable to native insect populations. Combined with their tolerance — historically, at least — for harsh city life, they were a valuable asset to urban forests.

For the new study, part of a larger, long-term project by the U.S. Forest Service, researchers planted clones of DED-tolerant elms in a range of urban conditions, from tranquil city parks to harsh sidewalks in three cities: Columbus, Ohio; Newark, Delaware; and Philadelphia.

“There’s many more stressors in urban areas than where we have them in the plantation,” said Cornelia Pinchot, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service who is managing the Ohio experiment. A street tree, for example, doesn’t have the protection of other trees, and may be exposed to excess salt or increased heat reflecting off pavement and concrete.

The elms, 135 in total, minus a few that didn’t “leaf out” this spring, are doing well, Pinchot said. They were planted last fall with the help of volunteers, but researchers will not know whether the trees are DED-tolerant enough for years to come.

“If you want to see the ultimate success of a street tree, you’re not going to have that answer for thirty years. Unless they all die in the first year, and then you have your answer,” Pinchot joked. “It’s just trees, you know, it’s slow.”

Danielle Mikolajewski, a graduate student at the University of Delaware, is studying what happens to the trees in the first year as part of her Master’s degree. She didn’t check on the trees much this spring because of coronavirus restrictions, but there wouldn’t have been a lot to see anyway.

“These trees pretty much look like big sticks. They look like a branch that was just kind of stuck in the ground,” she said. “The two that are dead just look like two long sticks without any leaves on them, where the rest of them have leaves now.”

Mikolajewski will be looking at how the trees are responding to where they’re planted. She’ll be recording how much the trees grow and their stress levels, and whether they are absorbing soil nutrients.

“If they don’t grow, who cares if they’re tolerant or not to Dutch elm disease?” she said. “We tried our best to plant them as best we could. Otherwise, we’re kind of just letting nature run its course.”

Maintaining the trees, which is being handled by the researchers to keep their care consistent, is pretty simple, such as mulching to prevent weed growth, watering and pruning.

Results may be slow in coming, but the inherited nature of the research is similar to the inherited nature of trees themselves, as much a part of city landscapes as buildings and monuments.

“It’s a long process involving many experiments, and this research was started many decades ago by scientists that have long since retired,” Marks said. “And each scientist over their career makes some progress towards the ultimate goal of restoring the species.”

Lillian Eden is an aspiring journalist pursing an M.S. in Journalism at Boston University.

This story was produced as part of NASW's David Perlman Summer Mentoring Program, which was launched in 2020 by our Education Committee. Eden was mentored by Chelsea Wald.