By Grace Niewijk

AUSTIN, Texas — Twenty Americans die every day waiting for an organ transplant, but some scientists think they have a solution to the shortage: growing human organs in barnyard animals. It’s already been a journey of over a decade, but they’re making progress.One key challenge is that the human immune system won’t accept an animal organ, so human cells have to be incorporated. Three researchers have reported a step forward, creating pig and sheep embryos that contained a handful of human cells.

“It’s like a science fiction story,” Stanford University geneticist Hiro Nakauchi said about cross-species transplantation during a Feb. 18 session at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting.

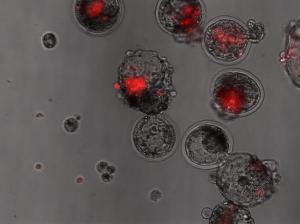

To make the latest hybrids — which were never carried to term — the teams injected human stem cells into balls of pre-embryonic sheep or pig cells to see if the human stem cells would be integrated into the growing animal along with its own cells. After a maximum of 28 days, the researchers dissected the embryos to determine where the human cells ended up. The analyses are ongoing, but the groups have already confirmed that the human cells were incorporated, with up to one human cell for every 10,000 animal cells.

To direct the stem cells to generate a specific organ in future experiments, the researchers propose starting with a mutant animal embryo unable to grow the organ needed for transplant. The human stem cells would then fill in the organ “gap” with a fully functional organ.

“We don’t expect to grow a human organ inside a pig,” said Pablo Ross, an animal scientist at University of California, Davis. “We expect to grow a pig organ full of human cells.”

That means the organ’s size and shape would be dictated by the host in which it grows, but the incorporated human cells should prevent a transplant recipient from rejecting it.

As a preliminary model for the ultimate goal, Nakauchi’s team grew a mouse pancreas in a rat and used cell transplants from that organ to cure a diabetic mouse. The researchers expressed excitement that these experiments provided proof-of-concept and helped them refine their technique.

Since there is more “genetic distance” between humans and livestock than there is between rats and mice, it’s more difficult to create animal-human hybrid embryos, Nakauchi said. That’s why the human-to-animal cell ratio remains so low in the current results, preventing organ transplantation into humans.

The next steps in moving forward from this milestone will involve working to help the two types of cells coexist more effectively within an embryo.

But the way to do so is unclear.

“There needs to be some major discovery before this is going to work,” Ross said. There’s still plenty left to figure out.

“A leading expert once said, ‘Xenotransplantation is the future of medicine, but the problem is that it's always going to be the future of medicine,’” said University of Minnesota cardiologist Dr. Daniel Garry. “There are so many challenges.”

In the meantime, Ross, Garry, Nakauchi and others plan to keep working toward a future that might be closer than many think.

“That could happen in a week — or it can take a long time,” Ross said.

Grace Niewijk is a senior at Yale University majoring in molecular biophysics and biochemistry. She is a staff writer for the Yale Scientific Magazine and serves as senior news and careers editor at the Journal of Young Investigators. She has done freelance work for Proto magazine, Medium, and the Jackson Laboratory. Follow her on Twitter and Medium @gniewijk or email gniewijk@gmail.com.