By Shanen Ganapathee

BOSTON — Living in peace with others in an increasingly globalized society can be a challenge, but ongoing efforts on a number of levels — scientific, economic, political and cultural — aim to help us understand and address the problem.

Credit: JelenaMrkovic/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

"The question is how do we create a more cohesive and committed society when the social scale is now the planet?" said Robin Dunbar, a professor of evolutionary psychology at Oxford University, during a Feb. 18 panel at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting.

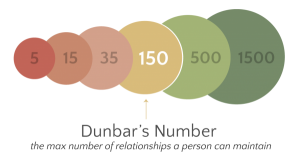

Using prefrontal cortex size as a predictor of group size in great apes, Dunbar concluded that prosocial behavior is limited by cognitive abilities. He further estimated that humans are cognitively capable of maintaining no more than 150 relationships. More than that requires additional "social grooming," for which there is limited brain space and time.

These constraints seem to come into play even when the pool of possible connections runs into the thousands or even millions through social media networks. On Facebook, for example, people tended to have no more than 150 friends, on average.

"We are designed to live in a very small social scale. In the super-large scale of the modern world, we end up living among strangers and we lose our commitment to the wider community," Dunbar said.

Clues about maintaining community have come from how children and adolescents behave, said Eveline Crone, a professor of neurocognitive developmental psychology at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

Her research team asked youths age 8 to 18 to play four types of games that tested preference for sharing with peers. They found that around age 12 or 13, adolescents experience a massive behavioral shift, becoming more generous toward their peers than before.

But there's a catch.

There seems to be a distinction between which of their peers the preteens and teens want to be nice to and which they don't, as a layering of their social circle occurs.

Dunbar concludes that we seem to have devised methods of creating a sense of who we are culturally, and why we belong with certain others. That sense of belonging can be cultivated through dance, music, language, ritual, storytelling, religion and other factors.

But cultural markers that bring people together can also keep them apart, as people tend to be more prosocial toward members they consider to be part of their "in-group" than they are toward those considered part of the "out-group." This can be seen from playground cliques to warring nations.

"There is unavoidably antagonism towards other groups. We create sense of belonging by contrasting us against the rest," Dunbar added.

As such, experts say, effectively addressing the challenges of globalization needs to involve a shared vision of the future.

Shanen Ganapathee is a senior at Duke University pursuing a self-designed major in Human Cognitive Evolution. She is from the small island nation of Mauritius. Reach her at shanen.gthee@gmail.com or follow her on Twitter @polymath94.