By Armi Rowe

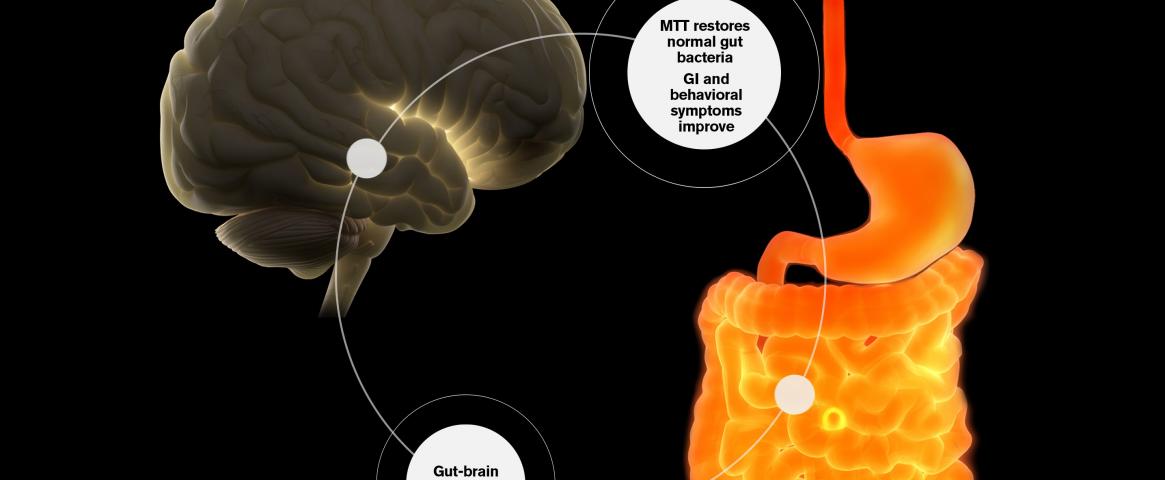

In a study led by Arizona State University investigators, 18 children received “microbiota transfer therapy” based on pills designed to introduce healthy bacteria. “We saw that these children had a decrease of many of their gastrointestinal symptoms, and their behavior improved dramatically,” said Rosa Krajmalnik-Brown, Ph.D., head of ASU's Biodesign Center for Health through Microbiomes.

Krajmalnik-Brown reviewed the promising early trial results, published in a 2019 Scientific Reports paper, during a session on gut-brain interactions at the AAAS meeting. Follow-on clinical studies among children and adults are now underway.

During the microbiota therapy trial, fecal and blood samples as well as behavioral and gastrointestinal assessments were collected from 18 children with severe systems of ASD. The treatment then included pills with bacteria generated from purified human fecal samples.

Analysis after two years confirmed that by improving the diversity of their gut microbes, the microbiota treatment helped restore balance in the children's digestive systems.

More strikingly, “symptoms of diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain and most behavior improved,” said Krajmalnik-Brown. Overall, the children displayed a 58% decrease in gastrointestinal symptoms and 45% decrease in the ASD symptoms since the start of the study.

James Adams, Ph.D. an engineering professor at Arizona State University who collaborated in the work, pointed out potential links between physical symptoms (such as migraines or chronic gut pain) and social behavior among children with the condition.

Adams suggested imagining the world of a child with ASD who also has inflammatory bowel disease that is resistant to therapy plus limited communication abilities. “You would feel generally miserable, much less able to learn and pay attention, and you might be anti-social,” he said.

“There are currently only two approved drugs for ASD and they only address irritability,” noted Adams, who has a child with the condition. “The study addressed the three core symptoms of ASD: language, behavior and social interaction.”

“This was a virtuous cycle,” added Herbert. “It is opening the doors to upgrading the system.”

Other experts cautioned, however, that the trial had relatively few participants and lacked a control group to allow comparisons with results for children given placebos.

ASU has begun a follow-up study on children with ASD who have gut issues in a randomized, double-blinded trial, which will use the same microbiota therapy but for 14 weeks. Half the participants will receive placebo treatments until the second part of the study.

Although the investigators expect that achieving the same benefits with older patients with autism and gastrointestinal problems will prove more difficult, they have launched a study testing the microbiota treatments on adults age 18 through 60. In this randomized, double-blinded trial, half the participants will be treated for eight weeks and the other half for 18 weeks.

Krajmalnik-Brown hopes such studies will help to identify which microbes, and which of the “metabolite” molecules the microbes produce, may help to boost health. “This would allow us to understand how and when the treatment works and when it does not,” she said. “It will also allow us to treat more people, if we can produce a defined microbial cocktail or use metabolites.”

Armi Rowe is a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University who will complete her Master of Arts in Science Writing degree in May 2021. She can be reached at arowe11@jh.edu.

This story was edited by NASW member Eric Bender, who served as Rowe's mentor during the NASW-AAAS Spring Virtual Mentoring Program.