By Kendall Powell

Like most freelancers, Alla Katsnelson and Amy Maxmen struggle with blurry lines. “It’s not clear how hard and fast are the rules” of freelancer ethics, Katsnelson opened. “How and when do you disclose conflicts of interest when pitching?” Often each situation is a judgment call and may be handled by editors and publications in different ways. The panel probed the opinions of three editors — Robin Lloyd, news editor at Scientific American, Apoorva Mandavilli, executive editor of SFARI.org, and Adam Rogers, articles editor of WIRED — and freelance writers Anne Sasso and Daniel Grushkin.

The session put each of the panelists in the hot seat to explain what position they would take for one of eight different ethical dilemmas that often crop up in freelancing. Audience members also cast votes to be tallied and presented by Maxmen at the end of the session.In one example, Rogers pondered whether a reporter should accept a ride from the airport, a pen, a hat, and/or a chicken lunch from sources for a story on organic farming. “If you are working for my magazine, you’d want to do all this stuff. That airport ride may be your lede. It’s a way to get at what the person is like.” Color, in other words.

“Yeah, if it’s for WIRED,” conceded Lloyd, but not for her online publication which needs far less color reporting. “Especially if it could indicate some bias accepting that material.”

Grushkin cautioned that usefulness to the story shouldn’t “rule the day” because “it might be useful for your story to do something [completely] unethical.” But Rogers reiterated that for the purposes of immersion in the story, eating lunch with organic farmers would serve the story best. Mandavilli pointed out that it might actually be important to sample the food produced by an organic farm. Especially if the chicken sucks.

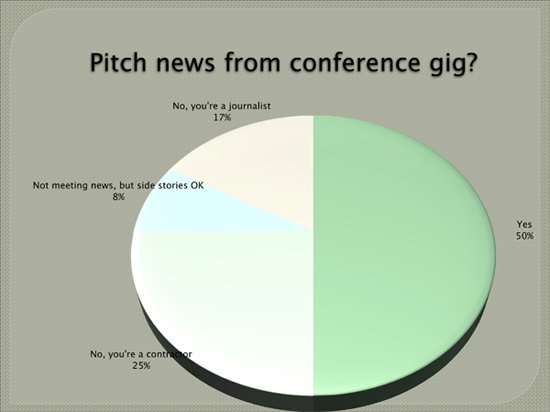

Another scenario involved a reporter hired to cover a scientific conference and write a summary. One of the speakers has interesting data. But can the freelancer pitch that idea to a news outlet?

Mandavilli took a hard-line “no” because simply the perception of a conflict of interest (COI) is enough to turn her off. “If you are doing journalism, being unbiased is number one for me. What I’m putting on my site is neutral and unbiased and my readers have to be able to trust that,” she said.

Sasso countered: “I’m all about writers making a living wage.” She asked if editors were going compensate writers for drawing lines around topics that writers absolutely cannot write about for them.

Grushkin offered transparency as the solution, disclosing potential COIs and letting readers decide on biases for themselves. Sasso flipped it around, asking the editors if it was more acceptable for freelancers to partition their journalistic beats away from topics they might cover as public relations consultants. For example, a writer doing PR for the pharmaceutical industry while reporting on engineered grass seeds. Rogers was stumped.

“I honestly don’t know. I’ve never had a writer say that to me. But my instinct is that it’s a problem,” Rogers said. “I’ve always thought there should be a bright line between journalists and publicists, but I’m also aware that rates haven’t gone up in 15 years.”

Lloyd acknowledges that most freelancers take on non-journalistic work. “I would love for us all to have stuck to the principles we learned in journalism school, but it seems that’s become impractical.” She suggested self-imposed limits that follow the simple test: Can you sleep at night?

Also see: Storified tweets from this session.