By Alison Fromme

Once I declared myself a freelancer, I embarked on what I called my own personal freelance writing internship.

Of course, there are lots of amazing internship opportunities at actual publications, and the NASW Internship Fair at AAAS is one great way to learn about them. But a conventional internship, like the one I did at the National Zoo's magazine, isn't what I'm talking about here. What if you can't up and move to a new city? What if the timing doesn't work out? In that case, you might want to consider creating your own freelance internship.

At the outset, I had a handful of contacts and a few published clips, but no actual, paying clients. I planned to see what I could do for three months and then assess my personal, professional, and financial well-being. I would learn by doing. And failing.It's tempting to get all dreamy about what an amazing freelance internship might look like. You're in charge! You could wander off to some far off land, or cozy up to some famous writers to absorb their genius. You don't have to get anyone coffee, except yourself. You can work in your PJs.

By all means, dream. But then prepare to face the reality of financial uncertainty.

Whether we like it or not, setting up our freelance shop requires us to consider how we'll pay the rent and manage our health care needs, often before we actually begin our adventure. For many people, managing money, especially at the beginning, is tricky. After all, we chose to write, not to become finance gurus.

As with any internship, I expected to be overworked and underpaid. Relatively risk-averse, I planned to make zero money my first year of freelancing. Hey, that would be better than J-school debt, right? I had saved a fair amount of money, my husband and I could live on his salary alone, and his job offered health insurance. We lived modestly in a cinder-block apartment in a crime-ridden Berkeley, Calif., neighborhood.

But that's not the only way to ensure financial security. Another option is to work a conventional job while you experiment with your entrepreneurial side. While Douglas Fox worked full-time as a copywriter at an advertising agency, he dreamed of being a journalist. "Because I had a day job, I started pretty slowly," Douglas says. "I fit all of my early reporting and writing into late nights and early mornings and weekends — all around the edges of a job that devoured 40-60 hours of my time per week."

If you think those long hours might be a bit too much, an alternative is to hang onto a part-time job, like Susan Moran did. She juggled part-time adjunct teaching at a university journalism school while starting her freelancing career. "It was a steady — if small — paycheck, and it kept me connected to budding journalists and academia, and to the world beyond the little package called 'me and my stories,'" Susan says.

Financial safety nets can take the form of savings, full- or part-time conventional jobs, or partners. We all need a roof overhead and food on the table. Exactly what you need beyond that is up to you.

And once you have that figured out, then you can start planning what you'll actually do when you show up for your first day. That will be covered in Part 3 of our Freelance 101 series.

This is the second installment of our four-part Freelance 101 series.

Alison Fromme is a contributing writer for Mountain Home Magazine and the founding editor of Hot Potato Press, a hyperlocal food news website. She's currently working on her first creative nonfiction book. Her writing has appeared in National Geographic, Backpacker, and the New York Times Learning Network.

Image of ABC mobile studio caravan by Australian Broadcasting Corporation [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

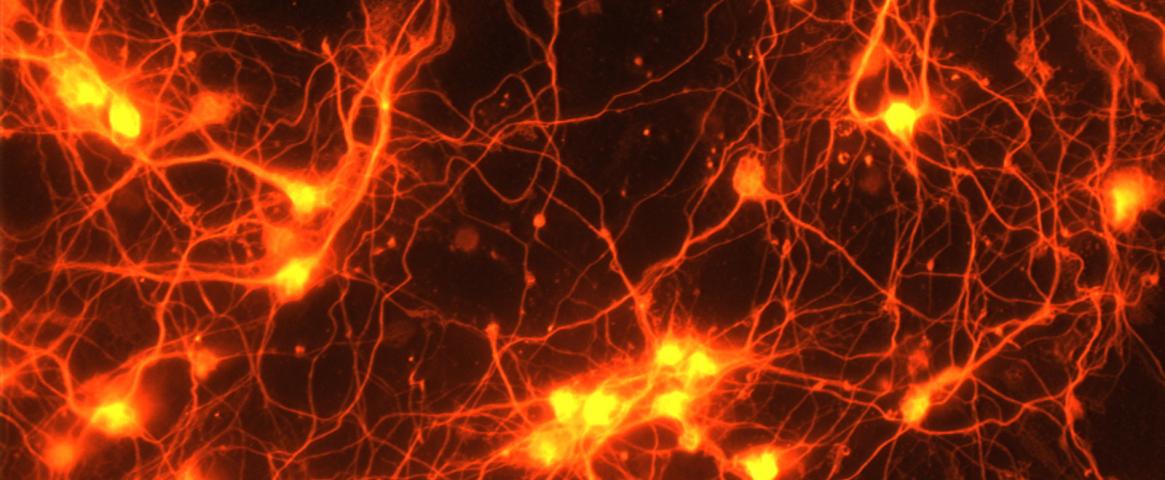

Image "GDF10 protein forms new brain cell connections" credit: NIH Image Gallery via Flickr/Creative Commons