By Abigail Eisenstadt

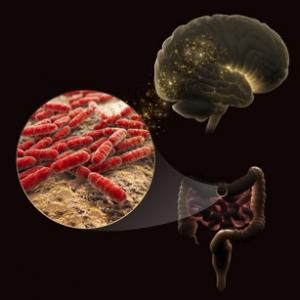

This community of bacteria called the microbiome can affect well-being, and this is particularly true in the gut. Scientists described new ways to study gut bacteria, and new discoveries about the many ways microbes affect health during a Feb. 16 session at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting.

Poor sleep, antibiotics, and even exercise habits can disrupt gut microbes, and, in turn, health.

“The gut is not Las Vegas,” says Rob Knight, co-director of the American Gut Project and a microbiologist at the University of California San Diego. “What happens in the gut does not stay in the gut.”

The gut can be thought of like a petri dish hosting many swarming species of microbes. When those species grow or die they can affect well-being very quickly. Changes can lead to immune disorders, allergies and other ailments. Current research has even uncovered specific combinations of gut bacteria in mice that can predict conditions like irritable bowel disorder and multiple sclerosis. If those findings replicate in humans, they could change approaches to treatment.

At the American Gut Project, Knight collects stool, tongue swab and other samples from people across the country. He puts many different microbiomes together with the aim of figuring out the composition of a generic human microbiome, and, ultimately, finding a way to control health through the gut. He envisions a “microbiome GPS” that would guide medical providers to the treatment their patients need.

But mailed-in samples don’t always show how bacteria act inside the gut’s ecosystem. That’s because it’s hard to recreate the oxygen-deprived conditions microbes need to flourish. Monitoring how bacteria grow and react in the gut requires simulation of the anaerobic conditions of the gut.

One way to do this is by engineering stem cells into a type of lab-grown gut tissue, called an enteroid. Growing enteroids around gut bacteria creates “mini bioreactors” that mimic the anaerobic habitat that most gut microbes need, said Joseph Petrosino, a microbiologist at the Baylor College of Medicine’s Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research. Tools like these could aid future studies that examine how tweaking the microbiome changes health.

A recent study gave one example of how diet might change the bacterial community in the gut. Led by Janet Jansson, chief biologist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, researchers found that mice put on a diet high in a special kind of hard-to-digest starch have increased sensitivity to insulin. Their microbiomes adjust to the new diet and make their bodies process insulin more quickly. If human trials show similar results, microbiome manipulation could be a promising way to treat diabetes.

Jansson, Knight, and Petrosino all are working toward the same goal: Using the microbiome as a tool to protect health. But will the recent discoveries make it out of the laboratory and into humans?

“That’s the bingo question,” Jansson said.

Abigail Eisenstadt is a senior at Johns Hopkins University majoring in English with minors in bioethics and history of medicine, science, and technology. She has worked with the University of Florida’s Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering Marketing and Communications office. Follow her on twitter @aeisenstadt1 or https://scienceeisenstadt.com.