By Emily Driehaus

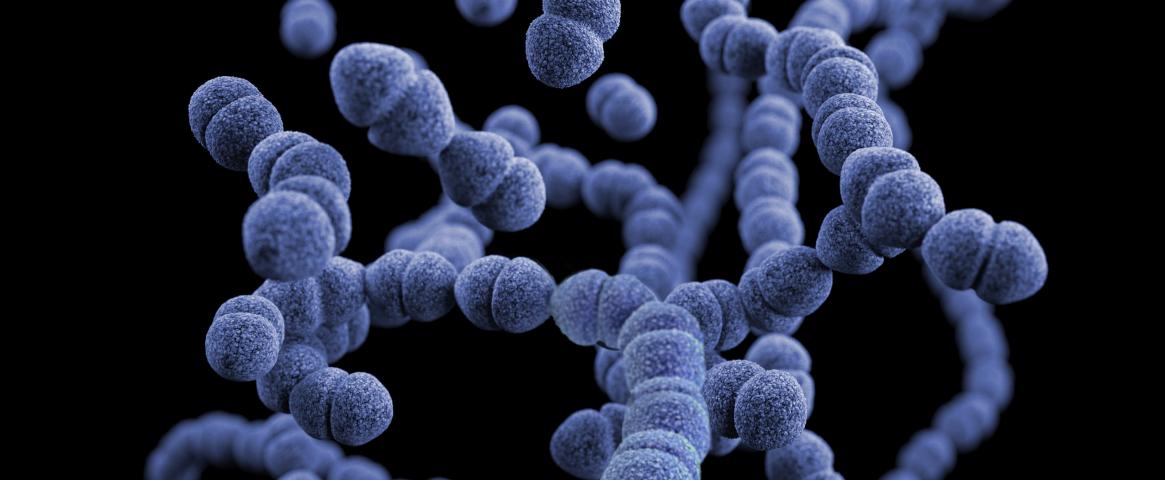

Deep in our digestive tracts, past our stomachs and nestled in our intestines, microorganisms have been helping us digest our food throughout human history while we have given them a place to live. Collectively referred to as the gut microbiome, these communities of microbes have been navigating their own form of climate change as our diets have shifted from foraged and hunted foods to mass-produced foods from the supermarket.

The gut microbiomes of our ancient human ancestors were more diverse than ours today, as they had to be prepared to eat whatever food they could find for survival. Our microbiomes today are less diverse, as our diets have become more standardized in the Western world.

While we do not have to worry about having the right microbes to digest foraged food, our lack of microbial diversity in our guts may have implications for our health. Studies have shown that a lack of diversity in our gut microbiome may be linked to diseases such as diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome.

Dr. Cecil Lewis is a professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma and has been studying human microbiomes for over 10 years. He says that our less diverse microbiomes are a result of our environment, which is what exacerbates the “diseases of civilization” we see today.

“It’s not that the microbiome is the source of the problem,” he said. “It’s more that we have become the problem, and this the microbiome we get based on our current behavior.”

Some microbes that were present in the guts of our ancestors are not necessary in our industrialized lives. For example, we have relatively low levels of parasitism in the Western world, so we do not need the microorganisms to fight off those infections that ancient humans may have encountered in their food. However, the absence of these disease-fighting microbes may come with health consequences.

“We’ve made our microbiome also a little naive, which means our immune system starts getting confused as to what’s a good guy and what’s a bad guy,” Lewis said. “And it starts fighting whatever happens to show up, even when it’s a good guy, and that’s how we get these autoimmune diseases.”

The phrase “heal your gut” has become somewhat of a buzzword in the health and fitness industry with increased research into gut microbiomes. Probiotic supplements are sold to introduce “good” bacteria into the gut, but Lewis says that some microorganisms are not inherently “good” or “bad,” but are a result of the environment we are giving them to live in.

“We want a friendly ecosystem because some of these bacteria only turn bad when the ecosystem is bad. They're normal bacteria that you should have in your gut,” he said. “But if that ecology gets disrupted, they turn into bad guys. But they're not bad guys unless we do something to turn them that way, we disrupt an ecology and make them have this opportunity to do things that we really didn't want them to do.”

Our relationship with our guts has changed throughout the course of human history. What was once a symbiotic relationship between certain types of bacteria and our body has taken on a new form as some bacteria have gone extinct and others have taken over their roles to compensate.

Dr. Stephanie Schnorr, a biological anthropologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who also studies ancient human microbiomes, says that this illustrates how adaptive our gut microbiomes actually are. Our environments are not as diverse as those of ancient humans, so our microbiomes have shifted from being tied to the environment to being more in line with our own bodies.

“The microbiome is a dynamic community that is adapting with our own environment and with the environment that we expose to it,” she said. “We have a bacterial community or a microbial community that exhibits traits that are very tied to our own bodies, and they fulfill a functional role that we need them to fulfill. It's just that they're no longer competing with so many diverse external bacteria or external sources.”

Schnorr is also interested in this link between the human genome and the microbiome genome in ancient humans. She says that looking into this link can provide more insight into how our modern bodies work with our microbiomes to carry out bodily functions.

“It might just give us a greater appreciation for how entrenched these communities are with our own phylogeny,” she said. “And it may help lead us toward thinking about personalized therapies.”

Emily Driehaus is a senior at Loyola University Chicago majoring in journalism and anthropology with a minor in environmental communication. She is an environmental science communication intern at Hydroviv and former intern at the Field Museum. Her portfolio can be found at emilydriehaus.com and she can be reached at emilydriehaus@gmail.com or on Twitter @EmilyDriehaus.

This story was produced as part of NASW's David Perlman Summer Mentoring Program, which was launched in 2020 by our Education Committee. Binder was mentored by Joseph McClain.

Hero image by CDC on Unsplash