By Lisa Aubry. Mentored and edited by Jeff Grabmeier.

Face masks worn during the pandemic unveiled insights into the ways humans process and interact with faces, scientists say. What is missed or acquired when faces are hidden? Recent research tackles this question by investigating the human face’s role in our lives from biological, psychological, and social standpoints.

“Compared to other parts of our anatomy, our face is most important in how others see us and in how we see ourselves,” said Jill Helms, a professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Stanford University.

Helms joined experts in psychology and brain science during a Feb. 20 talk at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting to tease out the varying impacts of face masks on perception, expression, and identity.

One repercussion of face masks involves how they hinder people’s ability to interpret emotional expressions displayed beneath a mask — and some facial expressions are more susceptible to this than others, according to research led by Paula Niedenthal, a psychology professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

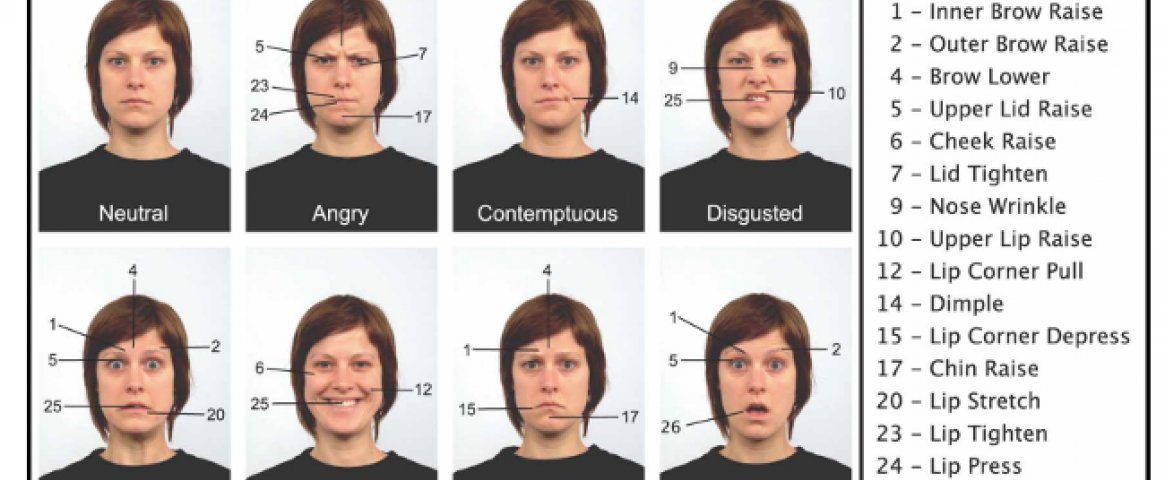

When masked, expressions of happiness and disgust are more vulnerable to misinterpretation than masked expressions of anger or surprise. Experts contend this is because happiness and disgust involve more facial signals in the lower face that gets hidden with a mask, as opposed to facial signals occurring in the top of the face like in anger or surprise.

Participants in Niedenthal’s study tended to rate happy facial expressions as less happy and disgusted expressions as less disgusted at higher rates than when judging expressions of anger or surprise. Further research conducted on more nuanced facial expressions, like types of smiles, yielded the same takeaways – masks can obscure the signals that facial expressions intend to convey.

Researchers believe that masks deter our ability to match the expressions we see on faces with the meanings we have for them in our memories. Additionally, not being able to see a masked person’s full expression reduces our ability to mimic their expression, an act that often facilitates feelings of empathy.

Misinterpreting facial expressions can start a domino effect, according to Niedenthal’s work. In addition to conveying emotion, expressions can also provide insights into the person’s intentions (what they may do next) as well as their attitude towards an event or object. When a perceiver misses such cues, their ability to successfully navigate social situations is compromised.

Because masked facial expressions become more ambiguous, people may try to enhance their message with body language, vocal affect, or even exaggerated facial expressions behind a mask to ensure their meaning is properly communicated and interpreted.

Helms said the shared, nearly universal experience of mask wearing presents an opportunity to tap into compassion and better understanding of others.

For a moment, people can begin to understand the challenges and social disadvantages faced by those on the autism spectrum who might be unable to convey or recognize the emotions behind our expressions, Helms said. For people with visible facial differences, wearing a mask may remove their face from the scrutiny they usually experience without a mask, in some way “leveling the playing field,” she said.

“If masks have led people to become more inclusive because we cannot see facial differences, we can take away that positive acceptance of people who look different from us even when we take off the masks.”

People living with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO), a visual disorder that disrupts the ability to properly perceive faces, can also experience a positive side effect of interacting with masked individuals, said Dartmouth College psychology and brain sciences professor Bradley Duchaine. People with PMO are known to see distortions — a drooping eye, a melting face, a crooked lip — in the faces of unmasked others and even themselves. Since the pandemic, they have reported a reduction or complete absence of facial distortions when observing masked faces.

All three experts agreed that many opportunities for face research have bubbled to the surface with the arrival of face masks. For instance, future inquiries may seek a better understanding of the way humans integrate information about emotion through facial expression paired with other sensory processes like body language and voice, as well as the possibility of generalizing the effects of masks on ability to recognize expression across cultures.

While masks continue to embody a myriad of meanings and consequences across individuals, the experts’ discussion also demonstrated how masks present an opportunity to dig deeper, and differently, into the significance of an asset that unites and diversifies humankind at the same time — faces.

Lisa Aubry is a graduate student in the Science Writing Program at Johns Hopkins University and a public relations specialist at an academic medical center. Email her at laubry1@jhu.edu.

Hero image: The diagram displays the facial signals, or action units, associated with common types of human expressions. This informed research led by Neidenthal Emotions Lab that led to the discovery of which facial expressions are more susceptible beneath a mask than others. Courtesy Paula Neidenthal.