Story by Alex Viveros

Photography by Ben Young Landis

The city of Memphis, Tennessee remembers the Rev. Dr. Autura Eason-Williams as a beloved and well-known preacher, activist, and leader who dedicated her life to improving the lives of people and under-resourced children in her community. She served as a pastor and district superintendent of her regional Methodist church, and spent years working with the Memphis Police Department on juvenile justice reform for the city’s at-risk youth.

“I learned everything from her,” Ayanna Hampton, Eason-Williams’ oldest daughter and a fellow Memphis activist, said. “She was a friend, sister, daughter, and just a person that everybody loved because everybody knew that they could come to her and not be judged.”

Eason-Williams was shot and killed outside of her home in Memphis on July 18, 2022. The alleged perpetrators were both 15 years old, and one of them had just been put under court supervision and was wearing an ankle monitor at the time of the crime. It didn’t take long for word to spread, with many local media outlets hammering on the fact that the children involved had a record.

Hampton was in downtown Memphis when her brother called her saying that their mother had just been shot. Within ten minutes, she was sitting in a dark hospital room surrounded by her siblings processing the news. As doctors offered their consolation, Hampton turned to her brothers and sisters with a chief concern — how would the media and community react to the shooting?

“I told my siblings this is about to blow up. My mother is very well-known here — I can’t go anywhere without seeing people that know my parents,” Hampton said. “To know that, sitting in that moment, we’re not going to be able to control how the story gets out there… We had to deal with a whole lot of other stuff because of the nature of the incident and who we are.”

Hampton shared her story to a room of journalists and writers at a panel titled “Gun Violence, Community Trauma, and the Journalist’s Role: A Memphis Conversation" (#MLK50atSciWri22) at the ScienceWriters2022 national conference in Memphis in October. A collaboration between the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing and the Memphis nonprofit news outlet MLK50, Hampton was joined onstage by Regan Williams, the Medical Director of Trauma Services at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital. Members of the Memphis community were also present, and the session was moderated by MLK50 publisher and editor Wendi C. Thomas.

To open the discussion, Thomas engaged Hampton in a one-on-one conversation about her experience — and what journalists should keep in mind when reporting on gun violence.

MLK50 publisher and editor Wendi C. Thomas introduces guest Ayanna Hampton. (Ben Young Landis/NASW)

MLK50 publisher and editor Wendi C. Thomas introduces guest Ayanna Hampton. (Ben Young Landis/NASW)

Considering political narratives

Many of Hampton’s worries about the media’s reaction to the shooting were fueled by ongoing debates about justice reform in Memphis’ political landscape. At the time of her mother’s passing, the county was locked into an election where a Democratic challenger was looking to depose the incumbent Republican district attorney. Their opposing policy stances on prosecution put questions about criminal justice reform at the forefront of voters' minds.

“You could see how this could be used as a campaign moment for this Republican incumbent,” Thomas said.

Soon after the killing, the incumbent District Attorney Amy Weinich announced that her office would prosecute both minors involved as adults, meaning the suspects could spend decades in prison if convicted. In a phone call to Hampton, Weirich claimed that such a move would be better for the alleged perpetrators in the long run — Hampton said that Weirich told her that the juvenile justice system wasn’t equipped to reform children who had committed such terrible crimes, and that the adult system had better support. Hampton, knowing Eason-Williams’ dedication to criminal youth justice reform, doubted that her mother would have wanted such a conviction.

Hampton held a press conference with local reporters to clarify her position. Standing alongside her siblings, she asked the District Attorney’s office to prosecute the suspects as minors, adding that more support should be given towards reform in the juvenile justice system.

“If I were to say ‘throw those children under the jail, charge them as adults, give them the death penalty, send them to jail forever,’ I wouldn’t have learned anything from my mother in 31 years,” Hampton said during the press conference.

Hampton recalled that one of the reasons she felt compelled to hold a press conference was because she wanted to ensure that media outlets clearly understood her position as an activist for juvenile justice reform. She felt that some media outlets undermined her perspective by only describing her as the child of a victim — while omitting her professional advocacy work.

“I’m not a child, I’m an adult that has researched these issues,” Hampton said. “Our position is not from some child-like naivete, we’re coming to you with data based on what we believe we’re called to do if you want to see something different happen in our city.”

Looking beyond the data

During the panel, Hampton was asked about what she believes journalists should keep in mind when writing stories about gun violence. She indicated that amidst rising numbers of shooting deaths, journalists should remember that real people are affected by such incidents and the angles that the ensuing stories take.

“These things happen to real people beyond the data,” Hampton said. “It’s so much more meaningful if you talk about how we got to this point rather than sensationalizing whatever you think is going to get attention.”

She turned to the case of her mother’s alleged shooter who had worn an ankle monitor during the crime as an example of how journalists could reimagine their stories’ angles. She felt that the narratives focused too heavily on labeling the young suspect as a repeat offender, rather than looking at how he could have been better supported.

“It could have had a completely different angle if they were actually trying to advance the narrative that we need better support services for young people in our justice system,” Hampton said. “The data is data, but how you use it is important. When you’re the person that has the power to use it, do something that makes a difference.”

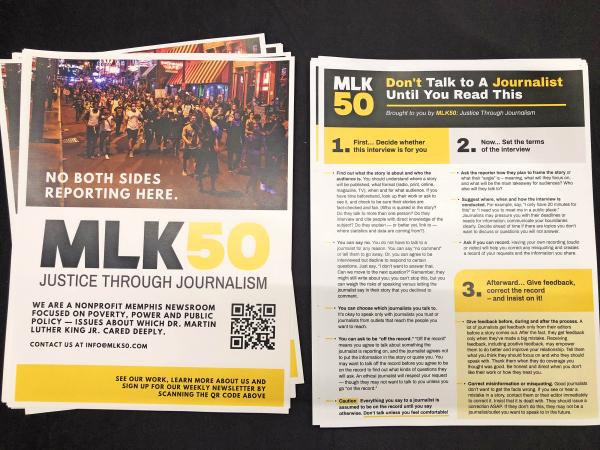

Handouts provided by MLK50 at the ScienceWriters2022 national conference. (Ben Young Landis/NASW)

Handouts provided by MLK50 at the ScienceWriters2022 national conference. (Ben Young Landis/NASW)

Teaching the public about interviewing

Journalists are often put in the difficult position of trying to impartially gain information from their sources while also being cognizant of the power they hold and how their words will affect their community. This is especially true for local reporters, who often live in and are engaged members of the communities they serve.

Accordingly, MLK50 states its mission focus as “the intersection of poverty, power, and policy — and how systems in Memphis affect the livelihood of working people. To accomplish this, Thomas highlighted that journalists need to establish a relationship with their communities based on transparency. “I live in this community and I want to do right by the people that are my neighbors,” Thomas said.

But while journalists are undoubtedly familiar with the reporting process, it can be easy to forget that many members of the general public aren’t familiar with what they’re signing up for when they agree to be interviewed. During the ScienceWriters2022 session, Thomas shared a tipsheet that MLK50 developed to give the public a better understanding of their rights during a journalistic interview.

The document, titled “Don’t Talk to a Journalist Until You Read This,” breaks down some basic guidelines on what to expect as an interviewee. Co-created by North Carolina-based journalist Lewis Raven Wallace, the MLK50 tipsheet describes how to agree to an interview, negotiate terms with journalists, give feedback, and avoid being misquoted. Thomas said that journalists also could use the resource to better answer questions from first-time sources.

“Journalism is an inherently extractive, exploitative profession — we ask people to tell us their personal details about their life, their finances, their health, their community, and then we write that information up and we publish it somewhere,” Thomas said. “We want journalism to break that extractive relationship and let people know what they’re signing up for when they agree to talk to a journalist.”

Alex Viveros (@alexgviveros) is a freelance science writer who has interned for Science Magazine and the Broad Institute.

This ScienceWriters2022 conference coverage article was produced as part of the NASW Conference Support Grant awarded to Viveros to attend the ScienceWriters2022 national conference. Find more 2022 conference coverage at www.nasw.org

A co-production of the National Association of Science Writers (NASW), the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing (CASW), and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, the ScienceWriters2022 national conference featured an online portion Oct. 12-19, followed by an in-person portion held in Memphis, Tenn. Oct. 21-25. Learn more at www.sciencewriters2022.org and follow the conversation on Twitter at #SciWri22

Credits: Reporting by Alex Viveros; edited by Ben Young Landis. Photography by Ben Young Landis/NASW