This student story was published as part of the 2023 NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring Program organized by the NASW Education Committee, providing science journalism practice and experience for undergraduate and graduate students.

Story by Emma Denes

Mentored and edited by Christina Nunez

Even with federal protections in place, the newly identified Rice’s whale remains in critical condition. What we choose to do next might bring them back from the brink of extinction — and conserve other species in the process.

In 2021, scientists identified the Rice’s whale, a new species found exclusively in the northeast Gulf of Mexico. The discovery of this genetically distinct whale may have come just in time to save it, with only about 50 individuals remaining, according to the most recent estimates.

Originally thought to belong to the Bryde’s whale species complex, the Rice’s whale was declared a species of its own after genetic and skull analysis. Today, the whales are safeguarded under both the <A href="https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/endangered-species-conservation/endangered-species-act">Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act in the U.S. The latter law forbids the harassment of any marine mammal, which includes the potential to disturb behavioral patterns.

Even so, fossil fuel interests in the Gulf continue to push forward and threaten the whale’s existence. The Committee on Natural Resources in the House of Representatives approved a <A href="https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/6008/text?s=2&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22:%22HR+6008%22%7D">bill introduced this past October by Republican Rep. Garret Graves of Louisiana, and it could limit the amount of conservation measures available to the species in relation to oil and gas activities.

All the while, scientists are still learning just <A href="https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01196">how much of the Gulf of Mexico the Rice's whale inhabits, but its range is uniquely limited. While other baleen whale species migrate seasonally, Rice's whales are the only ones to remain in the tropical waters of the Gulf year-round. That means all the dangers — and all the potential to mitigate them — lie in one critical place.

Environmental advocates argue that without specific protections, the Rice’s whale faces extinction driven by commercial human activity. And last summer, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration proposed a measure that would pave the way for those protections in the whale’s habitat.

Narrow habitat, numerous threats

After the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Rice’s whale population numbers declined by 22%, and one-fifth of females suffered from reproductive issues. Today, the Gulf still comprises the vast majority of fossil fuel production in U.S. waters.

Already, an oil and gas lease sale in the Gulf has been the subject of a <a href="https://apnews.com/article/gulf-of-mexico-oil-gas-leases-6bd0f8bd4281aea5fdc5fbf76b76b1bd>legal battle over acreage the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management excluded to protect the whale. The sale ultimately went ahead in December with the sensitive area included and resulted in <A href="https://www.boem.gov/newsroom/press-releases/gulf-mexico-oil-and-gas-lease-sale-261-results-announced">1.7 million acres of leased federal waters.

Beyond nonrenewable energy exploration, the whales face risks from ship strikes, underwater noise pollution and entanglement in fishing gear. In addition, they are very highly vulnerable to climate change, according to a <A href="https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290643">score-based assessment published this past September. And renewable energy development also poses a potential <A href="https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/09/wind-opponents-spread-myth-about-dead-whales/">non-lethal behavioral disturbance, as the first-ever offshore wind leases in the Gulf went up for auction at the end of last summer.

Under the ESA, the National Marine Fisheries Service is required to designate critical habitat for the Rice’s whale — a measure put forward for public comment in July 2023, with a decision likely to come this year. The proposed habitat area, which would span almost 30,000 square miles of water, follows research the agency has been conducting on the species.

“It gives us another action that we can work on with federal agencies and other partners and conservation groups to raise awareness about the habitat needs of the species,” said Grant Baysinger, contractor in the marine mammal branch of NOAA Fisheries Southeast Regional Office.

Federal entities already must consult with NOAA Fisheries on any activity that affects the Rice’s whale itself. The critical habitat designation would extend this requirement to activities conducted in the whale’s habitat not just by government agencies, but also by nearly anyone operating in the area under federal authorization.

Nonprofit groups Healthy Gulf and the Natural Resources Defense Council applauded the motion after both sued NOAA Fisheries in 2020 for failing to propose critical habitat earlier.

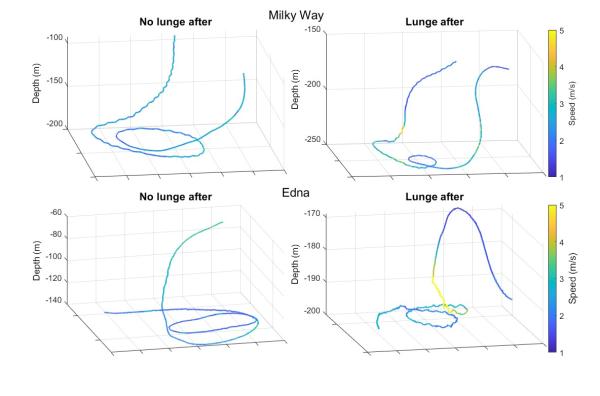

Image caption: Two tagged Rice’s whales, Milky Way and Edna, demonstrated circling behavior near the seafloor — putting them at risk of entanglement in fishing gear. Credit: Kok et al., 2023. Courtesy of Annebelle Kok.

Image caption: Two tagged Rice’s whales, Milky Way and Edna, demonstrated circling behavior near the seafloor — putting them at risk of entanglement in fishing gear. Credit: Kok et al., 2023. Courtesy of Annebelle Kok.

Slowing down not required

Advocates say NOAA Fisheries needs to implement further action to conserve the Rice’s whale, as is required under federal law. A petition sent to the agency on behalf of six environmental organizations, including NRDC and Healthy Gulf, called for a year-round 10-knot vessel speed limit in the Rice’s whale core habitat — this was recently denied by the agency in favor of additional recovery planning for the species.

The petition’s original requests were based on relevant research findings, including the proposal to require that ships avoid traveling in the habitat area altogether during nighttime hours. Rice’s whales are known to spend their nights resting near the sea surface, with one tagged individual spending 88% of its evening in such waters. When vessels traveling at those same shallow depths come into contact with a whale, the trauma can be lethal.

And according to a paper published in Scientific Reports, the whales forage for food by diving to the seafloor and circling their prey before lunge-feeding — a risky behavior in areas where bottom longline fishing gear is present.

“Because they are chasing their prey along the seafloor, they might not notice the lines being there, and therefore, get entangled into the lines,” said Annebelle Kok, the study’s lead author and marine biologist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

Making vessel speed restrictions mandatory has proven to be a successful conservation measure for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, of which there are less than 350 individuals left. Since 2008, federal rules have required vessels to travel at speeds of 10 knots or less during certain times of the year in Seasonal Management Areas along the Eastern seaboard. An analysis study of this mandate found it reduces ship strike risk for the species by at least 80%.

A need for more than speed regulations

Since Rice's whales are found primarily in U.S. waters, protecting them should be that much simpler, in theory.

“We know their core habitat, and what we need to do is to actually mitigate impacts within a small area,” said Jeremy Kiszka, professor of marine biology at Florida International University.

But such efforts will not go unchallenged, as port industry representatives celebrated the decision to deny the speed petition. They argue that its extreme proposals would have been a major disruption to the supply chain economy.

Even if the speed limit had been approved, it may not have been enough, as Kok adds that a whale detection system on board vessels might need to be considered as well. “I wonder if slowing down in itself is going to help — it might — but it could also be that they need something like lights or some other kind of detection device to be able to detect the animals,” she said.

Conserving the Rice’s whale is further complicated by the fact that they’re picky eaters. A paper published last spring discovered that almost 70% of their diet consists of a single organism: the silver-rag driftfish, a schooling species high in proteins and lipids. According to Kiszka, the study’s lead author, it might suggest prey availability is also an issue for these animals.

Including the Rice’s whale, 21 cetaceans reside in the northern Gulf. And even if the endangered listing applies only to two, including the sperm whale, protections would extend to the other whale and dolphin species.

“That’s not the goal of those designations and listings, but it does have conservation benefits as a side effect,” said Baysinger.

As time goes on, the decisions we make about how to save the Rice's whale serve as the ultimate test. “We know that there’s a lot of human activities, and the Gulf of Mexico is a major region of socioeconomic importance for the United States,” said Kiszka. “But at the same time, if we can’t save the species here in the U.S., what other species can we save?”

Main Image Caption: The Rice’s whale was only just recently declared a new species, but its population numbers are dwindling. Credit: Jeremy Kiszka.

A junior undergraduate student at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, New York, Emma Denes is a Communication major with a Journalism concentration and a minor in Environmental Studies. She regularly contributes to the Marist Circle student newspaper and serves as both its Assistant Managing Editor and Features Editor. Emma is also President of the Students Encouraging Environmental Dedication club and was previously a digital intern for Hudson Valley Magazine. Follow her on LinkedIn or email her at Emma.Denes1@marist.edu.

The NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring program is named for longtime science writer and past NASW President David Perlman. Dave, who died in 2020 at the age of 101 only three years after his retirement from the San Francisco Chronicle, was a mentor to countless members of the science writing community and always made time for kind and supportive words, especially for early career writers. Contact NASW Education Committee Co-Chairs Czerne Reid and Ashley Yeager and Perlman Program Coordinator Courtney Gorman at mentor@nasw.org. Thank you to the many NASW member volunteers who spearhead our #SciWriStudent programming year after year.

Founded in 1934 with a mission to fight for the free flow of science news, NASW is an organization of ~ 2,600 professional journalists, authors, editors, producers, public information officers, students and people who write and produce material intended to inform the public about science, health, engineering, and technology. To learn more, visit www.nasw.org