This student story was published as part of the 2023 NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring Program organized by the NASW Education Committee, providing science journalism practice and experience for undergraduate and graduate students.

Story by Christina Nowicki

Mentored and edited by Haley Wasserman

Everyone has had that moment – you come home from work, exhausted and hungry, looking forward to the leftovers awaiting you in the fridge. But instead of opening the Tupperware container to a delicious meal, you find yourself staring down at something fuzzy that surely shouldn’t be growing on pizza.

University San Marcos. Photo by Eline Becket

Although the blue soup has taken the spotlight, Dr. Becket’s primary research as an Associate Professor at California State University San Marcos focuses on a different, but equally interesting, topic. “My lab focuses on microbial genomics in near-shore microbiomes to figure out how urban runoff is affecting the evolution of communities, specifically through horizontal gene transfer.” Becket hopes to better understand how common antibiotics in urban waste can impact the movement of antibiotic resistance genes in coastal microbial populations.

To determine what bacterial species could be the culprit, Becket teamed up with Sebastian Cocioba, a fellow biologist, and began culturing the soup samples. With some patience and a little luck, eventually the bacterial communities began to turn blue. After identifying individual bacterial groupings, or colonies, of interest, including several iridescent clusters, they began growing each isolated bacterial species in the fridge, mimicking the blue soup’s conditions.

Blue bacteria being isolated on a plate of culture media. Different sections of the plate show that the blue pigment is dependent on the density of the bacteria. Photo by Sebastian Cocioba.

Blue bacteria being isolated on a plate of culture media. Different sections of the plate show that the blue pigment is dependent on the density of the bacteria. Photo by Sebastian Cocioba.

So, why the scientific intrigue? Natural blue pigments are rare in nature, and most “blue” foods, plants, and animals are caused by a deep purple pigment called “anthocyanin”, making the blue soup extra mysterious.

As the Twitter thread evolved, more and more scientists weighed into the debate. Pseudomonas fluorescent, a bacterium that can reportedly turn cheese blue, was the front-running theory as Becket and Cocioba continued to tease apart the mystery that had captivated the internet.

“What really added to this was the community,” said Becket “especially after three years of isolation, to be able to have this fun group activity across the entire world, with the only boundary being Twitter.”

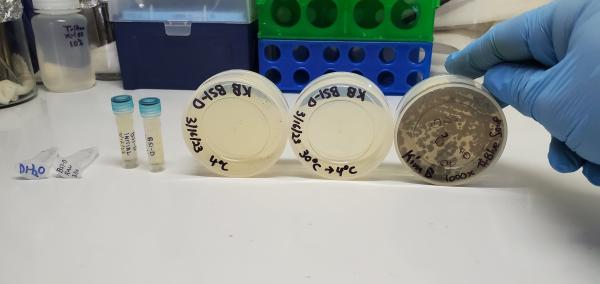

From left to right: Blue isolate to be grown at 4C, blue isolate to be grown at 4C and transferred to 30C, mixture of bacteria growing on a culture plate (including the “blue bacteria”. Photo by Sebastian Cocioba.

From left to right: Blue isolate to be grown at 4C, blue isolate to be grown at 4C and transferred to 30C, mixture of bacteria growing on a culture plate (including the “blue bacteria”. Photo by Sebastian Cocioba.

In addition to pining through cultures to isolate specific bacteria Becket and Cocioba used two different forms of genetic analysis to assess the overall community of microbes present in the beef soup. 16S sequencing, which looks at the genetic material from bacteria in the sample, showed that the soup primarily contained Pseudomonads, with some Enterobacter and Lactobacilli. Shotgun metagenome analysis provided a clearer picture by assessing all the genetic material in the sample, suggesting the blue offender was indigoidine produced by Serratia quinivorans.

Indigoidine is a natural blue pigment, similar to anthocyanin, the purple pigment in blueberries. Under specific conditions, some species of bacteria, such as Streptomyces, can produce this blue pigment but they are unable to produce enough to be used commercially. Researchers at Utah State University solved this problem by implanting the indigoidine-producing genetic machinery into another bacteria (E. coli), resulting in increased pigment production.

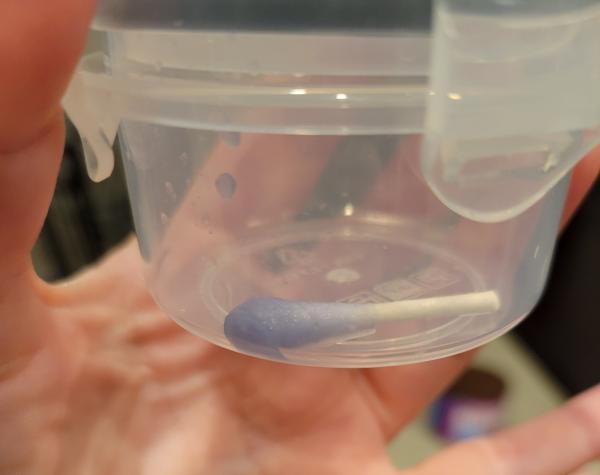

The swab Dr. Becket used to retrieve a sample of the blue soup. Photo by Eline Becket.

The swab Dr. Becket used to retrieve a sample of the blue soup. Photo by Eline Becket.

Becket and Cocioba are currently working towards publishing these results but shared some theories about what could be going on. “It is an indigoidine biosynthetic pathway that we saw, but maybe it’s a slight variation that is easier to produce or more environmentally friendly,” said Becket. While S. quinovans, our potential blue soup culprit, produces blue pigment, the colonies themselves are white. Becket said they theorize “most [colonies] are secreting the blue and some are actually sucking it up,” resulting in the shockingly blue soup.

While we’re still waiting for the answer to the Blue Soup Mystery Saga, “Something like this reminds us of what it’s like to be scientists – the joy and the curiosity” Becket said “This might be one of the stupidest, most useless things we've ever done but at least it's brightening our day and it's still teaching thousands of people about microbiology.”

Christina Nowicki recently graduated with her Ph.D. in Integrative Biomedical Sciences from Rush University, studying the intersection between microbiology and cancer. She is currently an intern for Drug Discovery News and VP for Communications for the Association for Women in Science Chicago Area Chapter. You can find her on her personal website (christinanowicki.wordpress.com) or follow her on Twitter @CA_Nowicki.

Main Image Caption: Blue beef soup that has gone bad and turned blue in the fridge. Photo by Elinne Becket.

The NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring program is named for longtime science writer and past NASW President David Perlman. Dave, who died in 2020 at the age of 101 only three years after his retirement from the San Francisco Chronicle, was a mentor to countless members of the science writing community and always made time for kind and supportive words, especially for early career writers. Contact NASW Education Committee Co-Chairs Czerne Reid and Ashley Yeager and Perlman Program Coordinator Courtney Gorman at mentor@nasw.org. Thank you to the many NASW member volunteers who spearhead our #SciWriStudent programming year after year.

Founded in 1934 with a mission to fight for the free flow of science news, NASW is an organization of ~ 2,600 professional journalists, authors, editors, producers, public information officers, students and people who write and produce material intended to inform the public about science, health, engineering, and technology. To learn more, visit www.nasw.org