Story by Helina Selemon

Photography by Helina Selemon

The Feb. 2023 train derailment and chemical spill in East Palestine, Ohio, started as a breaking news story that quickly evolved into an environmental and information crisis in the weeks and months that followed.

Eight months after the harrowing environmental incident, the ScienceWriters2023 national conference hosted a “Mistrust and Misinformation After Ohio's Toxic Train Disaster” Science + Science Writing session that illustrated how the spill became a more complicated issue to cover than economists, academics, government workers, and journalists anticipated.

The CASW-convened panel, moderated by Sharon Lerner of ProPublica, included a mix of experts who shed light on the complex issues surrounding the disaster: Andrew Whelton, a professor of civil engineering and ecological engineering at Purdue University in Indiana; Nick Messenger, an economist and senior researcher at the Ohio River Valley Institute; and Stephanie Czekalinski, the deputy editor of engaged journalism at Ideastream Public Media in Ohio.

Czekalinski said when word about the train derailment came at nearly 9 p.m. on a Friday night in February, her team wasn’t sure it was a story that night. “They happen pretty regularly,” she said. “Over the course of a career, you'll respond to probably quite a few, especially if you're in local news.”

The next morning, though, the story was starting to heat up — and by Monday, Feb. 6, “we are all googling ‘vinyl chloride,’” Czerkalinski said, referring to the chemical spilled from the derailed trains, nearly 116,000 gallons of which was set afire by response crews.

Three weeks post-derailment, it was evident to Whelton that the contamination was not as "contained" narrative initially put forth by government agencies and officials. By then, he and a team of volunteers had driven to Ohio to help test for and evaluate the spread of the chemicals and cleanup effectiveness. His team found that the areas between one and two miles from the spill site that were deemed safe were actually contaminated with harmful chemicals that devices approved for use were unable to trace. Residents in those areas were told they were safe to go back home.

“They were giving clean bills of health to these buildings that they were sending people back into,” he said. “And the people that were going in were getting sick.” So did government and contract workers and CDC employees.

The more chemical exposure and spread they found, the less was adding up for Whelton, the Purdue researcher. Messages from local and state governments, like Ohio Governor Mike DeWine’s office, were actively reassuring Ohio residents that the water was safe to drink. Whelton said the state didn't put any of the drinking water testing data online for three weeks but told everybody, "Don't worry about it. It's safe, we've tested it." And then when they started putting it online, he realized that they weren't actually testing for all the chemicals that were spilled on the train that they found in the creeks.

“So there were just a number of different incongruities between what they were saying and the response,” he said. After being repeatedly turned away from the county health department, the regional EPA office and the governor’s office, Whelton went public with his findings.

Long before then, the mistrust was brewing among residents who were desperate for information about their safety. Locals were hit with news and social media posts of Ohio Governor DeWine drinking the tap water, even while they could smell the chemicals in their homes and neighborhoods.

Journalist Stephanie Czekalinski thinks the government’s response and the media’s early reporting were some of the sources of distrust. “I'm not a scientist, but this doesn't pass my common sense test,” she said.

She found that East Palestine residents were growing more distrustful when difficult-to-answer questions about their health, homes, and family’s safety went unanswered, despite best efforts from reporters. She found it initially difficult to get residents to go on-the-record, but that quickly changed when residents saw no other way to get answers or make changes on the issue.

One of Czerkalinski’s deeply skeptical sources scraped together a decent understanding of what was happening by fact-checking leads from word-of-mouth statements, dubious disinformation outlets, and community Facebook groups. She told Czekalinski that she was raised to “believe nothing that you hear and only half of what you see.”

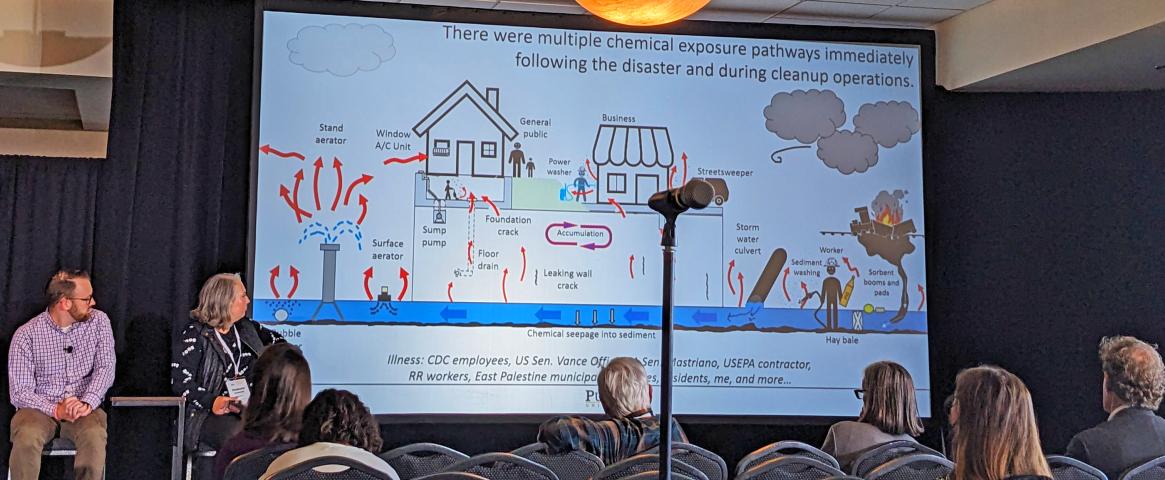

Panelists Nick Messenger and Stephanie Czekalinski looking at a slide with an illustrated figure showing the multiple chemical exposure pathways that occurred immediately following the disaster and during cleanup operations. (Helina Selemon for NASW)

Panelists Nick Messenger and Stephanie Czekalinski looking at a slide with an illustrated figure showing the multiple chemical exposure pathways that occurred immediately following the disaster and during cleanup operations. (Helina Selemon for NASW)

Lerner, the ProPublica moderator, said that elevating gaslit residents as primary sources was an important approach to the story. “We can't control what the EPA says, but part of what we're able to bring in as primary sources are the people who feel sick,” she said. “I had people who would whip up their inhaler or they'd show me the results from, ‘I went to the ER and look what they said,’ because they felt not heard and seen and believed.”

Nick Messenger, the economist on the panel, was blogging about the disaster by aggregating local and national news coverage of the event and observed the distrust that grew as the story got further away from East Palestine. He observed the media narrative shifted from a focus on the disaster's impact to a blame game, he said, with many questioning the safety of water and railroads near their homes. Poorly distilled into two-sentence public relations sound bites, complicated railway policies citing either the Obama or Trump administration further isolated readers and listeners into their own political camps on the issue, further polarizing the public response to the crisis.

“It wasn't just a problem right there with residents who were suffering the most, but that distrust became a regional phenomenon, and I think even a national phenomenon by the end of the month or so after the disaster,” he said.

The panelists shared the importance of pushing back on data with critical questions. Lerner advised pushing agencies, saying ProPublica called the EPA “like 15 times.” Her tip: Go back to agencies repeatedly. “It's uncomfortable, it is unpleasant… [saying] ‘I know you answered this five times, but here’s why I don’t believe you,’” she said.

Lerner also noted that the group hired by rail company Norfolk Southern to evaluate the derailment alongside the EPA had a history of conducting monitoring for train companies — and using the results to defend the companies in court. Making matters more confusing, the company, the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health or CTEH, worked alongside EPA workers, had distributed indecipherable data to East Palestine residents and sometimes even presented themselves as from the EPA.

The panelists hoped the conference discussion would keep the conversation about East Palestine going, as there’s more reporting to be done. When asked about how they dealt with disinformation, journalists Sharon Lerner and Stephanie Czekalinski said that they focused on reporting on the facts, though sometimes debunking myths along the way. Engineering professor Andrew Whelton's team has spent about $120,000 to investigate the spill and has since provided testimony to Congress. And there are still accountability threads to follow as the issue develops. Nick Messenger says that the work of economists has only begun in the aftermath of the train derailment: assessing the true cost of the disaster.

“When you have people still living in hotels, when you have people who are facing long-term health complications where the science of these chemicals are really going to manifest in 10, 20, 30 years down the road, and you have the railway company saying, ‘Well, we're gonna pay. Don't worry, we're gonna pay for the cost of the disaster, we're gonna clean it all up… as an economist, that cost is a lot bigger than the market cost,” Messenger said.

Helina Selemon (@HeyHelina) is a science journalist at The Blacklight, the investigative unit for the New York Amsterdam News, one of the oldest, continually published Black newspapers in the United States. Thanks to funding from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, she covers climate issues like extreme heat and health issues including COVID-19 and gun violence that center Black and brown communities.

This ScienceWriters2023 conference coverage article was produced as part of the NASW Conference Support Grant awarded to Selemon to attend the ScienceWriters2023 national conference. Find more 2023 conference coverage at www.nasw.org

A co-production of the National Association of Science Writers (NASW), the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing (CASW), University of Colorado Boulder, and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, the ScienceWriters2023 national conference featured an online portion Sept. 26-Oct. 3, followed by an in-person portion held in Boulder and Anschutz, Colo., Oct. 6-10. Learn more at www.sciencewriters2023.org and follow the conversation on social media at #SciWri23

Credits: Reporting by Helina Selemon; edited by Ben Young Landis. Photography by Helina Selemon; edited by Ben Young Landis.