By Jenny Cutraro

For much of my career as a science writer, I've stood in the intersection of a Venn diagram connecting science journalism, science education, and science outreach (or engagement, as we're calling it now).It makes me a bit of a misfit, being neither full-time journalist nor teacher nor PIO. But I've long thought these communities have a lot to offer to — and learn from — one another. Here's why.

I recently worked on a PBS KIDS science program called "Plum Landing." One of the things I most loved about this program was its effort to get kids to share their stories with us.

We invited them — through games, an interactive photo app, and a digital drawing tool — to go out into the world, record what they saw and what they did, and tell us about it. The key point here being that they told us, and not the other way around.

This got me thinking: Why don't we do more of this?

I started thinking about this even more when a colleague stood up during an American Association for the Advancement of Science symposium on science communication a few years ago and asked if we needed to change how we approach science communication. How can we make it more of a two-way conversation and less of a one-way delivery of information to the public?A few months later, I heard a talk by the late David Lustick, a White House Champion of Change for Climate Education and Literacy and associate professor of science education at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Lustick spearheaded a brilliant project using humor to bring climate change messaging to people on buses, subways, and other public spaces in Lowell and Boston. He also spoke passionately about Cool Science, a contest that asks kids to create works of art showing what climate change means to them. Winning entries are turned into posters displayed on city buses and transit stations throughout Lowell.

Like "Plum Landing," Lustick's program invited kids to be the messengers. He wanted to know what they had to say, wanted to give them a voice. I saw a lot of points of intersection in his work and our work on "Plum Landing," and used this for the basis of a symposium I organized for the AAAS annual meeting in 2016.

And that's when the idea of Science Storytellers began to crystallize. AAAS is unusual in the world of scientific meetings in its open embrace of non-scientists. Its two-day science festival, Family Science Days, offers free admission to the public.

It's also the perfect place to start the hard work of breaking down barriers and getting kids and scientists talking to each other. So last summer, I pitched an idea to the team at Family Science Days: Create a program where we ask kids to become storytellers for the day, giving them a place to tell us what science means to them.

AAAS green-lighted the proposal, and The Open Notebook's Siri Carpenter volunteered to partner with me to create this program.Importantly, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, which supports TON's early-career fellowship program, generously funded the design and production of materials we handed out at AAAS.

With this support, and the support of the many scientists and science writers who volunteered their time during the AAAS meeting, Science Storytellers came to life.

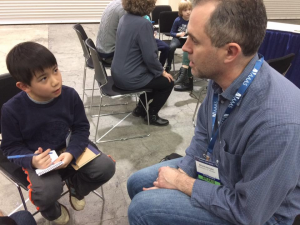

The concept was simple: Arrange a bunch of chairs to allow for face-to-face conversations, introduce a kid to a scientist, get out of their way, and let the conversations flow.

And flow they did. We had well over 500 visitors to the booth over the two days, a number that exceeded my wildest expectations. Close to 400 kids had a chance to sit down and talk one-on-one with a scientist, often in conjunction with a science writer who got the conversation started by modeling how journalists conduct interviews.

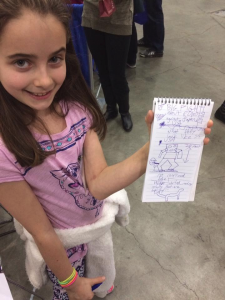

Over the two days, I stood back in awe of the excitement bubbling over at our booth. Scientists pulled out their phones to show kids pictures of their research subjects (limb regeneration becomes a lot more relatable when you can show pictures of the axolotls in your lab), kids drew pictures of the concepts the scientists talked about, and science writers demonstrated just what you do with a reporter's notebook.

At times, we ran out of scientists for kids to talk to one-on-one. When this happened, some kids grouped up, others stood in line, and one science journalist with a Ph.D. in ecology stepped in to talk about his research so kids wouldn't have to wait so long. Parents and younger siblings sat on the floor behind their kids, listening in.The program was intentionally unscripted and open-ended. We created simple handouts with basic conversation starters to help scientists and kids find common ground, and to then go a little deeper.

For the kids, we suggested questions they might ask: Did you like science as a kid? What else did you like to do when you were a kid? What do you study now and why are you curious about that? Why does your work matter? And for the scientists, questions like: Why do you like science? What else do you like to do? What's something you're curious about?

Then, we asked kids to complete a brief get-started-with-storytelling sheet for us. We included things like "This research matters because … " and "I was surprised to discover … " These, too, were intentionally open-ended, with no "right" answers, freeing kids to share insights with us like "I was surprised to learn that science is never ending," "This research matters because it helps us understand how we learn," and "Something I wonder about is can kids help scientists, too?"

The replies kids shared with us, and the popularity of this booth overall, confirm just how valuable it is to give kids the space and time to talk, to think, and to keep asking questions. It also revealed the value in giving scientists a chance to interact with kids at such a personal level. It's one thing to come visit a classroom to talk about research. It's another thing entirely to sit down for a chat.

I'm happy to say Science Storytellers will make a repeat appearance at AAAS 2018, in Austin. We're now turning our sights to other events such as science festivals, that might be ideal locations for us to run this program again. We're also thinking about how we might connect with after-school programs or other informal opportunities to help kids become Science Storytellers.

Jennifer Cutraro is a science and education writer and program developer in the greater Boston area who specializes in writing for kids and teachers. She also serves as a managing editor for the citizen science organization SciStarter's syndicated blog network on Discover, PLoS, and other outlets.

(NASW members can read the rest of the Spring 2017 ScienceWriters by logging into the members area.) Free sample issue. How to join NASW.