This student story was published as part of the 2023 NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring Program organized by the NASW Education Committee, providing science journalism practice and experience for undergraduate and graduate students.

Story by Caleigh Findley

Mentored and edited by Michael E. Newman

For decades, medical researchers have known that hormones greatly influence our brains. “Hormones, like estrogen, exert their influence on far more than just reproduction,” says Meharvan Singh, Ph.D., vice provost for research at Loyola University Chicago and a recognized expert on hormones and cognition. “Estrogen stimulates the birth and growth of nerve cells in the brain [neurons], keeps memory and reasoning powers sharp and helps shield our brains from aging-related diseases.”

This knowledge has empowered scientists to explore the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to reduce the risk of developing dementia. However, clinical trials from research groups, such as the Women’s Health Initiative, concluded that women undergoing combination HRT had approximately double the risk of dementia compared with those who did not. Now, researchers are digging deeper to uncover the missing link for HRT and women’s brain health.

“The key lesson from these trials is that most of the women participating were age 65 and older when they first received hormone therapy, “ says Rachel Buckley, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. “Given that the average age of menopause is 50 in the United States, that’s at least a 15-year delay before initiating potentially beneficial hormone therapy.”

Devastating age-related illnesses, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), emerge post-menopause and disproportionately impact women over men. For example, women are nearly twice as likely as men to develop AD and encompass two-thirds of all AD patients.

“Many scientists noted a higher prevalence of AD in women compared to men,” says Singh. “We wondered if the loss of protective hormones after menopause, like estrogen and progesterone, contributed to this sex difference.”

Researchers quickly found that the age of menopause onset is a risk factor for AD. Buckley says early studies showed women who had either natural or surgically-induced menopause at an earlier-than-usual age experienced faster rates of memory decline.

Previous studies showed that estradiol, the primary form of natural estrogen produced by the body prior to menopause, can directly influence the biological processes required for learning and memory formation. The neurons responsible for these functions have proteins on their surfaces that can recognize estrogen and then trigger a series of messengers inside the cell that support learning and memory abilities.

Aging takes this relationship and turns it on its head. Like a biological waterfall, menopause and its accompanying loss of estrogen sets off a cascade of resounding impacts on the brain and body. Lacking the estrogen support they once enjoyed, neurons become vulnerable to the very same biological insults that have grown over time.

“Due to these findings, many hoped that hormone therapy might be the key to reducing the risk for AD dementia in women,” says Buckley. “Unfortunately, clinical trials showed that successful therapy in animals doesn’t always translate to humans.”

The Women’s Health Initiative and other research teams conducted clinical trials using HRT around the time of menopause onset, but did not see the same negative outcomes as previous studies.

“Mind you, they haven’t found it was protective either,” says Buckley, “So, it’s still unclear what is going on in the brain when hormone therapy is initiated.”

Singh adds that four major variables — participant age, hormone therapy timing relative to menopause, type of estrogen used and the method of hormone replacement — can influence the response of women to HRT. Individual differences between participants, he explains, also create the possibility that some women are more likely to respond positively to HRT.

“This remains the topic of ongoing research,” says Singh.

Buckley and colleagues recently published a study in JAMA Neurology examining the timing hypothesis, investigating how the age of menopause onset and the timing of HRT impact key biological signs of AD. Their research has primarily looked at menopause and hormone therapy on signs of dementia, says Buckley, and less on biological signatures of AD in older women.

Buckley says the results support that earlier age at menopause onset and only late initiation of hormone therapy were associated with increased signs of AD. This, she says, to the growing body of evidence that HRT does not increase the risk of AD when timed appropriately.

All of the conflicting headlines about HRT and AD, says Singh, now come into focus: “Timing is everything and there is no one-size-fits-all answer for women,” he explains.

When considering the use of HRT to reduce AD risk, Singh says, “It is fair to recognize that hormone therapy may not be the right choice for all women. But at the same time, completely discounting its potential would be a disservice to many women who are likely to benefit.”

Buckley seconded the need for a personalized approach.

“For those women who are seeking more information or advice on what their specific situation should be for treatment of menopause systems, I would highly recommend speaking with their healthcare provider,” she says.

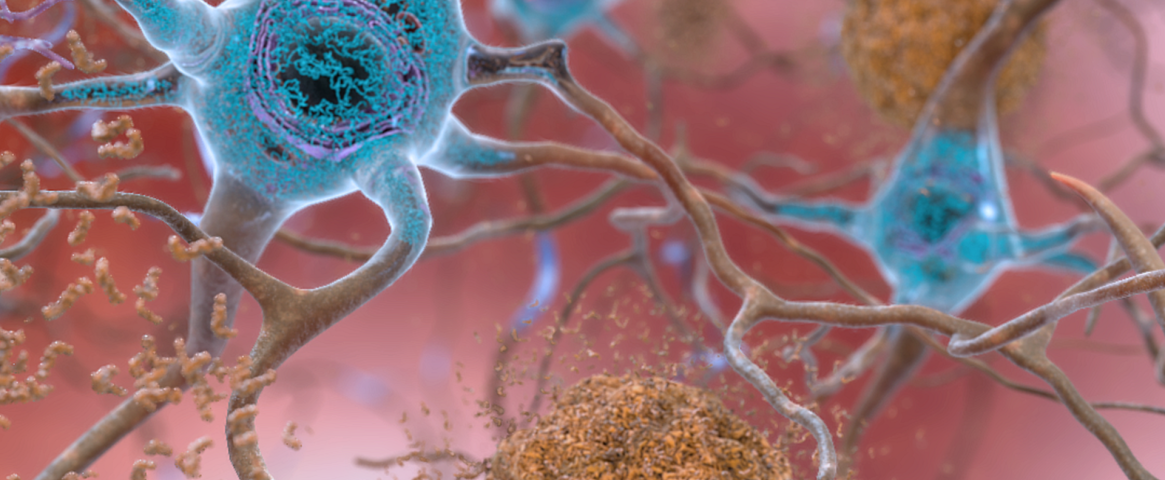

Main Image Caption: Artist’s rendition of an Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain. Abnormal levels of beta-amyloid protein (shown in brown) collect between neurons and disrupt cell function. A second protein, tau (shown in blue), excessively accumulates within neurons, harming intercellular communication. Recent research suggests that earlier age at menopause onset and late initiation of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) are associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s in women, and that HRT does not increase the risk of the disease when timed appropriately. Credit: National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health

Caleigh Findley is a science writer with nearly a decade of academic research experience in neurodegenerative diseases and pharmacology. Her work has been featured in Science Unsealed, ASBMB Today, Talking About Men's Health and diaTribe Learn. She received her doctorate in pharmacology and neuroscience from Southern Illinois University School of Medicine and her bachelor's in psychology from the University of Colorado Colorado Springs.

The NASW Perlman Virtual Mentoring program is named for longtime science writer and past NASW President David Perlman. Dave, who died in 2020 at the age of 101 only three years after his retirement from the San Francisco Chronicle, was a mentor to countless members of the science writing community and always made time for kind and supportive words, especially for early career writers. Contact NASW Education Committee Co-Chairs Czerne Reid and Ashley Yeager and Perlman Program Coordinator Courtney Gorman at mentor@nasw.org. Thank you to the many NASW member volunteers who spearhead our #SciWriStudent programming year after year.

Founded in 1934 with a mission to fight for the free flow of science news, NASW is an organization of ~ 2,600 professional journalists, authors, editors, producers, public information officers, students and people who write and produce material intended to inform the public about science, health, engineering, and technology. To learn more, visit www.nasw.org