By Nancy Allison

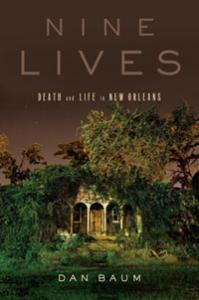

Writers need readers. We all want our share, especially when we've gone to the trouble of writing a book. How do we get them? Create a kerfuffle on the Internet. That's what Dan Baum did in May, just a couple of months after the publication of Nine Lives, when he tweeted a 4,338 word narrative about being fired from the New Yorker on Twitter.

It was a brilliant idea: turn tweeting on its head by using the 140-character limit in serial form. His 20,000-character story in reverse chronological order garnered Baum immediate online attention. Looks like that might have been what he had in mind. In the course of his tweets, he mentioned and pasted in a link to his website (along with fascinating tidbits about the inner workings of the New Yorker) no less than 20 times.

Soon, bloggers from Gawker to the Huffington Post were commenting on Baum, his nous, his pink hat, and his book. The LA Times books blogger Carolyn Kellogg called it a smart move, totting up the reasons we were reading the tweets and how many of us were doing so: "This is all juicy and delicious for journalists, falling somewhere between voyeurism, professional envy and Schadenfreude. Over the course of two hours this morning, Baum gained 200 new followers, from more than 800 to more than 1,000." The Times even posted Baum's YouTube video about the book.But it was a stray comment that Baum made — about all of the work going out under his byline being a result of collaborations with his editor (and wife) Margaret Knox — that really seemed to get people talking. Dana Goldstein, in The American Prospect, huffed over to Baum's website to find out more. Was Knox hiding her light under Baum's bushel? Was she getting a fair shake?

One thing is certain: Margaret was getting attention. All of the writing listservs I subscribe to were abuzz with questions and speculation about how Baum says they see the byline issue: "Dan Baum was just the name of the brand." Whether you agree with their thinking or not, branding is the reason that the website rolls with one name. Either way, you'll probably be tempted to check it out, which is exactly Baum's hope.

Baum created his site with Apple's free web authoring software (iWeb). As others have pointed out, iWeb is no Dreamweaver. But sometimes too many bells and whistles can be distracting. DanBaum.com is very clear and easy to navigate. More important, Baum makes the simplicity count. He includes a photo of the new book on nearly every page, and the YouTube video of him talking about the book on a page of its own. The buttons on the main page link to the New Yorker tweets; a new Twitter serial about how Baum and Knox freelanced in Africa; Baum's blog; Margaret's editing page; an invitation (and another video) to talk to book groups via Skype; and the Proposal Factory.The Proposal Factory is a brilliant stroke: I can't think of one writer who wouldn't jump at the chance to read a pitch that the New Yorker said yes (or no) to. Baum and Knox open up their files and show proposals that worked and those that didn't, as well as "before Margaret" and "after Margaret" versions of stories. All of these factors conspire to make the site unique. That it's a delight to read and helpful to other writers is a bonus that one rarely finds on the Web.

I caught up with Margaret in Boulder and Dan in Montana last week. Dan was in Montana working on a story that didn't pan out. Not one to waste a trip, he wrote about it in his blog, Wordwork, which he then tweeted was up and running again. The blog, of course, has menu buttons up top, which link back to the website, the book, the articles, the video, the book reviews, and the About/Contact page. Now that, my friends, may be called the "author as brand" — but I just call it good marketing.

NA: Dan, you have been accused of using Twitter to (gasp!) market your book. On The Rumpus blogger Sean Carman sends up the New Yorker tweets as shameless self-promotion. Do you mind?

DB: I don't mind, but I think it's naive to think that writers won't try to draw attention to themselves and their books. Of course I was using Twitter to market my book. It's said that all press is good press. Maybe that's true. I certainly like it when people are talking about my book.

NA: Margaret, a response in the New York Observer to Dan's Twitter-serial in May portrayed you as the unsung woman behind her man. The author seemed to hint that you were less than happy with the one byline arrangement...or at any rate, should be. How did you feel about the piece?

MK: I gave the Observer article a quick glance and of course, winced. It's always hard to be written about. You say things in a certain context, and the interviewer has to select what interests her. Quotes end up in the writer's context, not the source's. Even when an article is right in all the details, which an intimate piece rarely is, it feels wrong. It feels like a caricature. That's the nature of the collaboration between interviewer and interviewee. On the bright side: when writers are written about, they learn something about what their sources suffer.It's an adventure to work editorially with someone you know so well and have known for so long. Dan and I edit each other, but for paying work, he's migrated more toward reporting, while I've headed toward editing. What I'd really like to do is to figure out how to write a novel. I've been working on one sporadically over the years, and Dan's editing has always been useful. When I have the time and courage to finish it, he'll be there with all his insights and criticisms.

NA: Funny how other people seemed so distressed on your behalf. I'll bet you won't put Dan's name on the cover of your novel! How about the website: is that a joint project between you?

DB: No, not really. When I bought my new MacBook, I signed up for a year of one-on-one lessons at the Apple Store and spent several lessons learning iWeb, Apple's web-building software. It's incredibly easy to use.

NA: How is the site working for you, in terms of pulling in folks who want help with manuscripts, buy the book, or assign you stories? How do you know that your site is working? Any suggestions for writers who don't yet have a website?

MK: We get lots of work off the website. It feels as though word of mouth, which used to be limited to neighbors, friends, and colleagues — and a few degrees of separation — has grown to include the whole world. We get business from writers in Mongolia and Korea! I've got outdated web-building skills and should make time to learn what's possible. Instead, I play hammered dulcimer.

DB: We have a lot of clients for both Margaret's editing and the Proposal Factory, my proposal-coaching service. That pays us a little extra money, which is very helpful right now. But it hasn't resulted in any assignments.

NA: Is the site doing what you had hoped it would do ... what was that, and how do you know?DB: The site is a fine place for people to go, but the other half of the equation is doing things to get them to the site in the first place. That is why, in part, I did my Twitter stunt re my time at the New Yorker, and the one about launching our freelance career in Africa. I also "attend" book groups via video Skype, which people seem to like and which, I hope, will inspire people to read Nine Lives in their book groups. I am hoping to do more of that when the paperback comes out in February 2010. Overall, it seems that writers need to make news themselves in order to remind the reading public that they, and their books, exist.

NA: Do you charge a fee for "appearing" at book club talks?

DB: I don't charge a fee. It's an honor to be invited. I've visited quite a few book clubs via Skype and it works great. Generally, I limit it to about twenty minutes, since that is about all people can stand of talking to a computer screen. But I'm hoping it gets more book groups to read Nine Lives.

NA: The secret-sharing aspect of your site is addictive to many readers, including me. You post proposals that worked and those that didn't, and show us pre-Margaret and post-Margaret drafts, letting readers see what goes on behind the curtain. Margaret, I love the picture of you outlining the book on a piece of paper so huge you had to tape it to the wall. Is that how you always begin — pen to paper?

MK: That usually happens a good ways into the process. On magazine articles, I don't think it ever happens before at least a first draft. If we're considering various ways of structuring a story, we'll print out the draft, cut it up, and lay it out on the Ping-Pong table. We'll use pens to write new transitions or make notes on changes needed, as we figure out the structure. For the New Orleans book, the outlining happened when much of the reporting had been done, and we wanted to see how themes and events resonated, from one character to the next. The book has an odd structure, and it's hard, at the beginning, for some readers to take in nine big characters. But there's something in it that tugs at readers subliminally; a lot of the enthusiasm for the book may have to do with the care we took in structuring it.NA: You also edit for other writers.

MK: I've been offering editing services for a while, and I was getting quite a bit of work, helping people shape, report, and polish queries. We realized that on the querying side, whether for book-length projects or magazine articles, Dan had more recent experience. He's been the point man for us lately, and understands those relationships well. He's also a natural salesman. So he created the Proposal Factory, and I often send people to him, at least for initial advice on proposals. When a proposal is short and specialized, I may still handle it. Or when a book proposal includes chapters, I may participate in the editing of those. But mostly I edit full articles, books, or short stories, either before or after they've been sold.

NA: Dan, tell us more about the Proposal Factory. Do writers get in touch after their pitch has been rejected, before they send it, or both?

DB: Sometimes people get in touch because they have an idea for a story but need help developing it into a proposal. In those cases, we start with a brainstorming session on the phone — usually half an hour or an hour. In many cases, they need coaching in how to go about reporting the proposal as well as writing it. Then they write a draft, and we begin the back-and-forth until it's ready to submit.

Some people already have a draft, or a proposal that was rejected at a magazine, and they want to revive it. Usually, in those cases, we start right in with the edits. Often, though, a long phone conversation is needed somewhere along the way in those cases as well.

NA: Do you help people who are just starting to learn the ropes?

DB: I work with experienced writers and with total neophytes. Sometimes, in addition to editing, what writers need most is a kick in the pants. Sometimes they need a cheering section. This is a lonely business and I find that often my most useful addition to their process is letting them know that a) they're not alone, and b) what they are attempting is eminently possible.

NA: That sounds great. I wonder if I can afford you.

DB: I charge $75 an hour, which includes talking on the phone, editing copy, and reading and responding to emails. Usually, magazine proposals can be knocked into shape in three hours or less. Book proposals, naturally, take longer. I haven't yet had a writer tell me the time and money spent wasn't worthwhile. A couple of hundred bucks to take a proposal from a vague idea to a sellable pitch is really pretty cheap. I should probably charge more, but as freelancers ourselves we are acutely aware of the need to hold costs down.

NA: Margaret, do you ever talk clients through the editorial process, and what would you think about video-conferencing for that?

MK: I have a fiction-writing client here in Boulder for whom I edit a chapter a week — or a short story, if that's what he's working on — and then we meet at a coffee shop and discuss changes. It helps us understand each other's intentions and concerns. For others, it's occurred to me that a marathon retreat session at the end of a book project might be useful, because when a writer has gone over something several times, the last push can be really discouraging and lonely. Mostly, once I've returned the marked-up copy, we chat by email. But I've also worked on the phone, and video-conferencing might be an even better idea, for building a trusting and supportive relationship.

NA: Between the two of you, who gets to make the last call?

DB: It rarely comes down to someone making "the last call" over the other's objections. It took me about a decade of marriage/working together for me to figure this out, but Margaret is almost always right. When we really disagree about a particular phrase, I usually walk away from it for a day or two, and when I come back, I almost always see her point and go with her version. But in a small number of cases, I stand my ground, and she's gracious about it.

NA: Any advice for freelancers who are struggling just now?

DB: From working with freelancers at the Proposal Factory, I notice that a lot of people underestimate how much work it takes to write the kind of proposal that will result in a good magazine assignment or a book project. There are a lot of specific techniques that I get into with my clients, but overall, I'd say to freelancers that however much work you thought it was going to be, double it.

Nancy Allison writes about the fascinating research, art, and scholarship occurring at universities, in galleries, and on the web. She blogs at Writer on Board. Send your web and blog picks to her at: nancy@nasw.org.