By Stephanie Parker

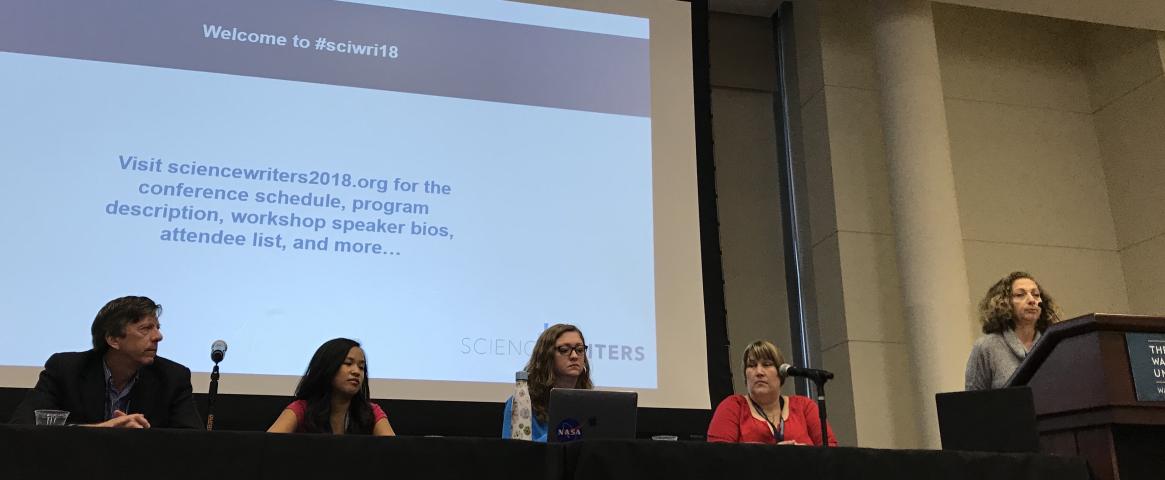

What are the benefits of having a beat in science journalism? What are the drawbacks? And how do you become an established beat reporter in a certain area? These are some of the questions tackled at the "We've got the beat: How to create an area of expertise as a science writer" panel moderated by Cori Vanchieri of Science News. The four-person panel offered perspectives on beat reporting from a print journalist, radio journalist, freelancer, and a public information officer (PIO).

The panel was formatted as a Q&A with questions from an online survey along with audience questions. Panelists discussed the many benefits of having a beat, such as cultivating strong, long-term sources, which can lead to unique and interesting stories.

"It's about being in the right place, knowing who to talk to," said panelist Jon Hamilton, a science correspondent for NPR covering, among other things, the neuroscience and environmental health beats.

Tina Hesman Saey, who covers the molecular biology beat as a senior writer at Science News, added that she gets sources in her field to come to her with interesting research and stories by explicitly asking them to. And Chanapa Tantibanchachai, a senior media relations representative at Johns Hopkins Medicine recommended that PIOs go to relevant faculty meetings to find sources in their beats.

However, panelists also discussed some of the drawbacks to having a beat. One audience member asked about the possibility of getting stuck in a niche so specialized that it's hard to branch out. Freelancer Rebecca Boyle, whose beats include astronomy, physics, deep time, and climate change, talked about the "FOMO" (fear of missing out) of not getting to write certain stories, like covering the recent IPCC climate report.

Audience members learned some fun information about how panelists chose, or fell into, their beats. Boyle, for example, moved from political to science writer after reporting on birth control for geese as part of a local government story. She ended up pitching it as a more focused science piece to Popular Science and never looked back.

Panelists also discussed what a "typical" day in the life of a science beat writer looks like (hint: there isn't one). There were insightful conversations about what it means to be a trained scientist who has moved into the communications field. Hesman Saey mentioned the importance of remembering who you're writing for, and keeping in mind that you need to write science not for another scientist, but for your non-scientist neighbor. And after a comment from "double-agent" scientist and freelance writer audience member Doug Fields — that every scientist has been burned by a journalist who didn't get the facts right — Hamilton stressed the importance of double and triple checking complicated concepts with your scientist sources.

Session attendees left with a lot to consider, whether or not to pursue a beat, best practices for writing great science, and how to cultivate a beat of one's own.