By Hosen Arman

An old or defective immune system ages the rest of the body of the mice, a recent study reveals

When we age, sickness hits us harder and longer. Our immune system — our defender against invaders — becomes less fit to fight bacteria and viruses. Scientists have suspected that our aging immune systems might contribute to decreased function in other organs, though how it works has been a puzzle. Now, research shows that deleting a DNA repair gene from the immune cells of a mouse prematurely ages those immune cells -- and spreads signs of aging throughout the rest of the animal.

The immune system's job is to take out the trash, to kill and get rid of damaged or harmful cells. But when the immune system itself gets old, it doesn’t do that job so well, which can lead to things like liver damage, kidney damage, and cancer. “Not only are these immune cells not doing their job of taking the trash, but they are making more trash,” says Matthew Yousefzadeh, a gerontologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. “What we are trying to do is dissect out the individual contributions of cell types or organs towards the total aging of the organism.”

To better understand the role of immune cells in aging, Yousefzadeh and his colleagues set out to increase DNA damage in mouse immune cells. When there is DNA damage in our cells, a protein complex called Ercc1-XPF forms a scissor to cut out damaged DNA. The scientists deleted the gene Ercc1 in mouse immune cells. Without the gene and the protein complex it makes, DNA damage persisted in the mouse immune cells, producing mice with artificially aged immune systems.

When the immune cells were aged prematurely, not only did they stop clearing out the debris from the body, but they started releasing inflammatory chemicals and tissue damaging materials into other types of cells in the mice. Those cells showed the presence of various inflammatory and highly reactive chemicals, which are normally seen in old mice. When the researchers transferred those prematurely aged immune cells into other young mice, they saw symptoms of aging in those young mice as well. Conversely, when they replaced those prematurely aged immune cells with young immune cells with the Ercc1 gene, they reduced signs associated with aging. The scientists were also able to reduce the symptoms of aging in the mice with the aged immune systems by using drugs that stimulated the immune system to action. Yousefzadeh and his colleagues published their results on May 12, 2021 in Nature.

"I think one should cautiously consider whether we are witnessing a true aging effect or a more general immunosuppression effect,” says Anton J.M. Roks, a pharmacologist and vascular aging and disease expert at Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. Roks recommends that future studies evaluate different organ systems to see if they are truly experiencing aging in their cells.

Finding out which immune cells are contributing to the effects will also be key, says Yousefzadeh. The immune system, after all, isn’t a monolith. . “We deleted the genes from a number of different immune cell types, but what immune cell types—whether it is B cell or T cell or macrophages—are doing the most of the work remains a big question,” he says. In the future, he aims to investigate the contribution of various parts of the immune system towards overall aging of the body.

Hosen Arman is a research technician in a Thomas Jefferson University microbiology lab. He recently graduated from Rutgers University Camden with a degree in biology and a minor in psychology. Follow him on Twitter @Hosenmarman or email him at hm.arman@rutgers.edu.

This story was produced as part of NASW's David Perlman Summer Mentoring Program, which was launched in 2020 by our Education Committee. Arman was mentored by Bethany Brookshire.

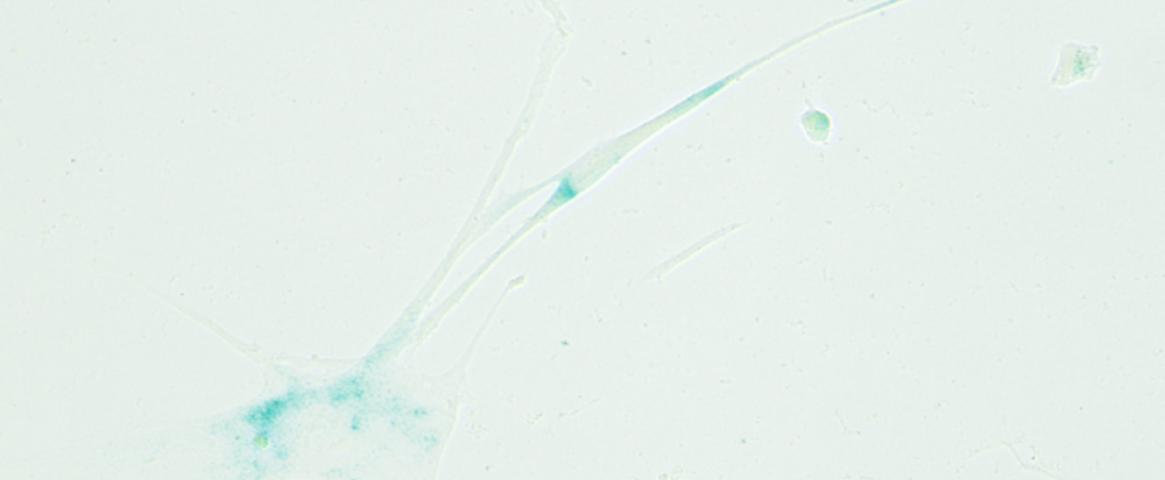

Main image: When cells lose the ability to continue cell division, they are known as senescent cells. They can cause inflammation in aged individuals. Credit: Matthew Yousefzadeh.