On science blogs: The human brain, journalism, Darwin's finches

THE RETURN OF JONAH LEHRER: CODA (PERHAPS). Catching up on a couple of pieces on the Jonah Lehrer apologia that have appeared since last week's episode. Catching up because they make points more somber and more serious than the rollicking bashing the rest of us engaged in. More somber and serious because they are not so much critiques of what Lehrer did (although they are) as critiques of Lehrer as a science writer emblematic of much that is wrong with science writing.

Philosopher of science John Wilkins complains that Lehrer's writing was inaccurate not only because he purloined from others or invented quotes but because he invented points of view on neuroscience that twisted the research and distorted its findings.

Wilkins sets Lehrer in the context of the way science writing is practiced. Which is that it can't just relay the facts about research, it must present a story, a narrative full of conflict and drama.

… this is not only a failure of the entire field of science reporting, whether on blogs or in published outlets (or both), but of the very field and profession of journalism itself. What you read in the successful mass media is not factual, nor complete, but a story, a narrative. And narratives have to have conflict. They need to have drama, or they will not be published, and if they are, they will not be read.

I understand exactly what he means. And so do you if you, too, have struggled to drape naked research results in a story line contrived to sell an article to an editor. And so do you if you have snatched at any old anecdotal lede for your own stuff, or raced through the anecdotal ledes of others in order to get to the part with the facts.

Wilkins cites a post by psychology prof Christopher Chabris, who argues that the sins of making things up that Lehrer has been chastised for are like the ways in which he gets the science he writes about wrong. He gets it wrong because he reshapes neuroscience findings for dramatic effect.

… the fabrications and the scientific misunderstanding are actually closely related. The fabrications tended to follow a pattern of perfecting the stories and anecdotes that Lehrer — like almost all successful science writers nowadays — used to illustrate his arguments … It's human nature to be more convinced by concrete stories than by abstract statistics and ideas, so the convincingness of Lehrer's science writing came from the brilliance of his stories, characters, and quotes. Those are the elements that people process fluently and remember long after the details of experiments and analyses fade.

Much to ponder here about the craft of science writing. Last week many of us greeted Lehrer's vow to impose new rules on himself with catcalls. We argued that he didn't need new rules, he just needed to abide by the old one: If you're writing nonfiction, you don't get to make stuff up. But Wilkins and Chabris are saying that just sticking to what happened is not enough.

Wilkins, in fact, thinks the whole idea of narrative journalism (all kinds, not just science and medical journalism) is hopeless. All those conferences and seminars and articles and courses about narrative journalism that have gripped nonfiction writing for the past several years are a complete waste of time. In his view, the need to impose a story line makes it impossible to serve up the truth.

Chabris is not so much blaming Lehrer as he is the human brain. I don't think he means to excuse Lehrer's behavior exactly, although his post is a bit more sympathetic than the excoriations the rest of us engaged in. But Chabris emphasizes the story that has recently been told about Homo sap, which is this one: Our brains have a hard time with discrete facts and abstractions. We insist on being told stories instead. In short, Lehrer was simply acceding to what the human brain demands.

BAM GOES THE BRAIN. Speaking of the human brain, Christopher Chabris has also been mulling over plans for the Brain Activity Map project described this week. In fact, his is one of the few blog posts I could find about it. I guess it's early days yet. You can get the background on BAM and quotes from the New York Times piece from Robert Gonzalez at io9, an unabashed enthusiast.

It struck me that these early BAM discussions sounded very much like the talk surrounding the Human Genome Project back in the last century when it was just a twinkle in Jim Watson's eye. And in fact BAM's backers have made the analogy explicit, contending that the Human Genome Project has returned $140 — or maybe $141 — to the economy for every one of the estimated $5.6 billion spent on it.

Chabris calls that $140 figure "preposterous" and notes that it comes from a report backed by Life Technologies, the California company that makes gene sequencers. Ahem.

Chabris is intrigued by the idea of BAM but wonders if it will really pay off. Might the money might be better spent in other kinds of neuroscience research, "by letting a thousand flowers bloom rather than planting one ginormous tree."

Over at Cosmic Log, Alan Boyle interviews the prominent BAM backer, uber-geneticist George Church, who tries to calm some of the competitive fears by saying BAM would not necessarily be new money. Instead it will simply involve new technologies that would uncover neural function more efficiently and cheaply.

Um. We'll see. There will be much, much more of this.

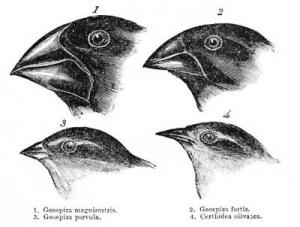

DARWIN'S FINCHES HAVE THEIR DAY. In all the hullabaloo about Jonah Lehrer last week, I neglected to call your attention to a landmark event that occurred on Darwin Day, which this year had the misfortune to fall also on Fat Tuesday and therefore got Lehrer-swamped.

That event is the first genome analysis of one of Darwin's finches, the large ground finch Geospiza magnirostris. You can get to the open-access PDF from the Abstract, which is here.

Jonathan Eisen, a senior author of the paper, explains at his blog The Tree of Life that there is a long long long story behind the paper, which was originally supposed to happen as a celebration of Darwin's bicentennial birthday in 2009. Many hurdles ensued, one of which was getting DNA to analyze. The Galápagos finches are heavily protected and collection of samples on the archipelago is highly regulated.

The paper's authors observe that the genome study is important beyond what it reveals about finch biology. That's because bird species have been undersampled compared to mammals. The Order Darwin's finches belong to, the passerines, accounts for half of the world's 5000 or so bird species.

OBAMACARE UPDATE: THE NEWS ABOUT THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT IS HUGE, JUST HUGE. First of all, more than half the states have decided to let the federal government set up the individual state health exchanges where all medical insurance will be purchased. There are some who disagree, as Sarah Kliff explains at Wonkblog, but I don't see how this can be anything other than terrific news. Many have also decided to accept the federal offer to pay for expanding Medicaid, the program that insures the poor.

I hope I don't have to eat my words, but it seems to me inevitable, just inevitable, that putting the feds in charge will mean that similar rules will be imposed in the 26 participating states — and since that's more than half the states, those rules will also shape insurance offerings in the other states. This has got to be the beginning of the end for the 50 separate state fiefdoms that have rendered US health insurance the befuddling and chaotic mess that it is. Who knows, it may even get cheaper. Well, I guess I shouldn't go that far.

That is not to say there won't be an even worse mess to begin with, as all this stuff gets organized. But eventually things will settle down. Whatever you think about Medicare in principle, in terms of insurance procedures it functions pretty efficiently from a consumer point of view, and there's every reason to think the same will also happen — eventually — with Obamacare.

If you're any kind of ironist, you have to just love the politics of this thing. Putting the feds in charge of health insurance sales is, no way around it, the beginnings of socialized medicine here in the US. It's a de facto start on the single-payer system that many Democrats wanted all along.

A single-payer system is what Republicans decried early and often. Yet most of the governors who washed their hands of Obamacare by turning its insurance exchanges over to the feds are Republicans. So, isn't it wonderful, it will be the Republicans who are bringing us socialized medicine.

Other juicy tidbits in Kliff's piece: The insurance exchanges must offer mental health coverage. That is huge, although in practice probably not perfect. I can't imagine that Obamacare won't impose severe limits on talk therapies because they are so much more expensive than pills, even when the data indicate they're effective.

However, a little-noticed feature that is potentially even more huge is that medical insurance must include pediatric dental coverage. A century from now perhaps old folks will be routinely keeping their teeth.