On science blogs this week: iPad

IPAD, IPAD, IPAD, IPAD, NEW IPAD. The Onion's piece "This Article Generating Thousands Of Dollars In Ad Revenue Simply By Mentioning New iPad" also generated the idea of opening this post with Apple's latest. Ads aren't a factor on this site, but it would be of interest to learn whether a post mentioning the new iPad (and mentioning it and mentioning it) would generate more than the usual number of visitors. Call it a small test of the craze for Search Engine Optimization.

I did at least find a couple of sorta relevant blog posts for linkage. At Digital Book World, Jean Kaplansky mused about what changes the new iPad might mean for e-books. For instance

More pixels and additional processing speed provides unique opportunities to support new user experience features and opens an array of new possibilities across the eBook, and in particular, the enhanced eBook, landscape.The new iPad will undoubtedly raise consumer expectations and thereby the bar for what qualifies as a quality eBook.

Raising, along with the bar, the question of whether e-book clones of regular printed books, the mainstay of the e-book market so far, have much of a future. Already a handful of e-books reject the label "book." They call themselves apps. Is that the future of the book?

At Technology Review, Christopher Mims opines that the retina display and much-improved resolution of the new iPad means much bigger content files, which in turn probably means a sorry future for the cheapest iPad, the $500 16GB version. But the splendid new iPad display, he argues, will also accelerate the move from print to tablets.

I probably won't be getting an iPad, especially if Mims's forecast about the inadequacy of the cheapest model turns out to be true. At Buzzfeed, Doree Shafrir shares my thinking. Although unquestionably I regret being shut out of the iPad-only books — excuse me, apps — like some reviewed at Download the Universe.

BE AWARE THAT BRAIN AWARENESS WEEK STARTS MONDAY. Brain Awareness Week, which goes by the unlovely acronym BAW, begins Monday. BAW is the Dana Foundation's baby. But it provides an excuse to make you aware of some recent blog posts about neuroscience.

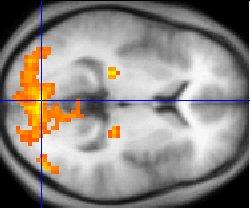

Brain imaging studies are favorite topics for science writers, but the fact is that their validity and methodological drawbacks make them controversial among neuroscientists. At BishopBlog, Dorothy Bishop, a developmental neuropsychologist at Oxford, links to a few recent professional critiques.

She also skewers a highly cited 2003 paper presenting fMRI studies on dyslexic children that was published in PNAS. The hed on the post is "Time for neuroimaging (and PNAS) to clean up its act," which will give you the flavor.

Something like a happy ending crowns this tale, which might have been just another doleful post on Bad Science. One of the authors of the 2003 paper recognizes its shortcomings. Russ Poldrack, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Texas, Austin, has been born again to become an imaging-study gadfly himself. The hed on his post is flavorful too: "Skeletons in the closet." Poldrack responds to Bishop's post thus:

Looking back at the paper, I see that Dorothy is absolutely right on each of these points.

Wow. Now that's brain awareness! Not only a handsome admission, but nearly unprecedented.

One solution Bishop urges is that some selfless imaging expert volunteer to put together a crib sheet listing the things that would help less knowledgeable readers evaluate the Methods section of imaging papers. Maybe Poldrack would do it? Being one of those less knowledgeable readers, I'd like a Methods-clarifying crib sheet too, please.

Poldrack's post is not a simple crib sheet that would help us ill-equipped science writers do a better job. But it does go into useful detail about common methodological shortcomings in imaging research. Some of these are all too familiar, often plaguing not just imaging studies but an uncomfortable proportion of the scientific literature as a whole. Among them: small sample sizes, small effect sizes, and the pressure to hype that is attendant on being in a hot scientific field.

(Thanks to Neurocritic for the tip.)

These are not just academic quibbles. Shoddy science has the potential to leak into our lives. For example, this week Deric Bownds speculates at Mindblog:

An MRI scan may soon be part of the interview process for jobs requiring skill at learning and performing novel tasks.

He's referring — ironically, I hope, I hope — to a new paper (PNAS again!) claiming to show "that individual differences in performing novel perceptual tasks can be related to individual differences in spontaneous cortical activity." In other words, an MRI scan can predict a person's performance at a new task. Scary if true, and even more scary if debatable and yet swallowed whole by personnel directors, school administrators, parents — and science writers.

GORILLA GORILLA GORILLA GENOME. Also relevant to brain awareness, at least tangentially: The last of the ape genome sequences was published this week. That would be the genome of Gorilla gorilla gorilla, in the person of a resident of the San Diego Zoo named Kamilah, a member of the subspecies western lowland gorilla.

News stories puzzled over the fact that a gene involved in hearing, known as LOXHD1, seems to have evolved just as quickly in the gorilla as in Homo sap, perplexing if the gene relates to speech, as had been thought. Paleoanthropologist John Hawks, who has been studying the gene, provides an explanation:

The connection with language is only indirect, in that human-specific changes to this and other genes provide evidence of adaptive change in the auditory system.

At Neuron Culture, David Dobbs quotes Hawks and points out the common mistake of assuming that because a gene is involved in a trait, it actually codes for the trait itself.

Implicit here is another mistake: overlooking the multigenic nature of complex traits and abilities. How might the LOXHD1 gene be crucial to both gorillas and humans but (help) generate different auditory traits in each? Because it works with different sets of other genes in the two species, and, of course, vastly different physical and social environments.

For a very nice explanation of the auditory system that is also, not coincidentally, a lovely primer on how genetic characteristics are passed from one generation to the next, (aka Mendelian inheritance) and also the evolution of human hearing, see the Hawks classroom lecture video posted here.

THE FIRST AMERICANS WERE EUROPEANS. John Hawks also has the briskest analysis of the recent resurrection of a far-out idea: the New World was first settled by ice-age refugees from the Iberian peninsula. These folks, it is argued, were an offshoot of the Solutrean culture, which occupied settlement sites in southern Europe and featured uniquely worked tools (but no fossils). The sites date to about 21K BP. The argument is that Solutrean émigrés eventually fathered the Clovis culture on the other side of North America. But Hawks explains:

There is no new evidence, no revelation, no reason why other archaeologists should revisit this issue at this time. The news is free publicity for the release of a book.

Which book shall remain nameless here, although I will point out that co-author Dennis Stanford has been peddling this outré notion for well over a decade — and that the near-universal response from his archaeology colleagues has been the horse laugh.

A point of interest, however, is that Razib Khan, at Gene Expression, is urging something approaching a modicum of a teeny bit of a smidgen of cautionary restraint with the horse laugh.

My own current estimation is that there is a 99.5 percent probability that the basic outlines of the Solutrean hypothesis are false (that Paleolithic Western Europeans traversed the North Atlantic ice, that the Solutrean culture substantively contributed to the Clovis culture). I don’t say 100 percent because the past few years have indicated that certainty is something you shouldn’t adhere to with much ardor in the area of human prehistory.

Or, indeed, in any scientific endeavor. Suppose, for instance, that there are neutrinos faster than light? Or, more relevant to Khan's point, suppose (as I noted here last week) that Otzi's genome, which is not typically European today, was typically European when he was murdered 5600 years ago? As Khan observes:

The ultimate answer may be that real prehistory was more complex and strange than heterodox models proposed by “bold” archaeologists.

Khan has more to say about mongrel humanity at another post this week. For a quick summary of the Solutrean notion, pro and con, see K. Kris Hirst's short piece at About.com.

Although his post at io9 is mostly skeptical, Alasdair Wilkins does call the idea of Solutrean Americans "intriguing" and, the ultimate accolade, "neat." He also makes glancing reference to one implication of the Solutrean notion that stirred so much ire when it was first announced. That's because it argued that the First Americans were not migrants who crossed from Asia to Alaska around 15K BP (which notion is strongly supported by evidence from several sources, including genetic evidence), but instead came five thousand years or more before that, brought with them superior technology, and were European and, by implication, white. Or at least as white as anybody was 20,000 years ago. To many, the idea (which originated in the 19th century, and that fact alone may explain a lot) seemed not only loco, but racist.

Hawks says he would like to evaluate the Solutrean claims, but although the book's publicists have labored hard and been rewarded by lots of media attention, apparently the book itself is not yet available. So its claims can't be analyzed at the same time they are being promulgated in the media. As Alasdair Wilkins would say, intriguing. Not to mention neat.