On science blogs this week: Junk too

HAPPY NEW YEAR, BOYCHIK. Just in time for Rosh Hashanah comes a new New York City regulation on ritual infant circumcision. This amid renewed debate about the benefits and risks of the ancient surgery, an uneasy amalgam of medicine and religion.

Yesterday (September 12, 2012) the New York City Board of Health voted unanimously to require written parental consent for metzitzah b’peh because they believe it to be a source of disease transmission, specifically herpes infection. Scott Helmsley reported at the NPR blog Shots.

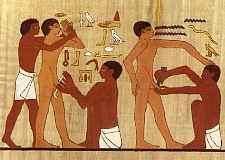

Metzitzah b’peh is a Talmud-endorsed form of ritual circumcision practiced among the most orthodox of Orthodox Jews. In metzitzah b’pehm the mohel, after slicing off the foreskin, takes the baby's penis into his mouth along with a sip of wine and sucks blood from the wound.

At the Hasting Center's Bioethics Forum, Dena Davis says the Talmud justifies metzitzah b’peh "so as not to bring on risk," which could certainly mean prevention of infection via the alcohol in the wine. But in New York City, the CDC reports, metzitzah b’peh has infected 11 boys with HSV-1 since 2004, including 2 cases of brain damage and 2 deaths, with another 2 in New Jersey. The CDC estimates that about 3600 infants go through metzitzah b’peh every year.

Jewish groups have protested the new consent regulation, calling it an interference with freedom of religion. That's becoming quite a refrain these days. But aside from the danger of infection, a nonbeliever like me can reasonably regard the procedure as, at the very least, quite creepy. Especially given the continuing disclosures of molestation of children, especially young boys, by authority figures such as Roman Catholic priests — although I guess no one has attempted to justify that loathsome practice as a religious ritual.

Metzitzah b’peh was also condemned in circumcision recommendations issued last month by the American Academy of Pediatrics, although AAP cited several reasons why conventional medical circumcision could contribute to health in later life. Elizabeth Reis noted, also at the Hasting Center's Bioethics Forum, that no one can accuse AAP of not being flexible on the question of infant circumcision. I have seen this odd history described nowhere else. Reis says that, while AAP may have concluded this year that there are good medical reasons for infant circumcision, the group concluded in 1999 that such reasons were slim, in 1989 it concluded the opposite, and in 1971 it "officially concluded that it was not a medical necessity."

I haven't gone back and read the recommendations Reis was referring to, but from her account it's not clear how serious are the differences between them. You might argue that, just as in 1971, the August statement also concluded that infant circumcision was not a medical necessity, since it declared that the decision to cut or not to cut belonged to the boy's parents. But Reis regards what she calls the AAP flip-flopping as reason for parents not to rely on medical authority here.

I doubt that the recent AAP statement will have much effect on people's existing attitudes toward circumcision. Some examples:

-

For the Skeptical Ob, ob-gyn Amy Tuteur, the statement only confirms her long-held belief that circumcision prevents HIV infection and AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases, and cancers of the cervix and penis.

-

OTOH, Deena Blumenfeld is a childbirth educator for Lamaze International who acknowledges that she prefers boy babies to remain intact. She also says she discusses circumcision in her classes, but doesn't describe what she says.

-

At Science-Based Medicine, SkepDoc Harriet Hall tries to analyze critiques of the AAP statement, but in the comments gets heavily critiqued herself.

- Jesse Bering has a long post at his SciAm blog Bering in Mind describing his semi-nasty dispute with columnist/blogger Andrew Sullivan over circumcision. (He's pro, Sullivan is not.) The comments are also worth a scan. My favorite is this simple analysis of circumcision's effect on world affairs from the ever-prolific Anonymous:

It leaves psychological scars — why are the Jews and Muslims at war? They were all circumcised as babies and view the world as a dangerous, painful place.

In short, circumcision is one of those ostensibly scientific topics, like climate change, where facts are either endlessly disputable or beside the point.

UPDATE ON THE UNCERTAIN FUTURE OF DISCOVER BLOGGERS. No real news yet about the fate of the Discover network bloggers like Carl Zimmer, Ed Yong, and several well-known others, discussed here last week. I am guessing that they are probably the best-paid science bloggers around, and Knight Science Journalism Tracker Paul Raeburn reports some details, for example that a bonus is added to their monthly flat pay depending on the number of readers they draw to the site.

THE SCIENTIFIC DISPUTE OVER THE ENCODE PROJECT, PART 2. Continuing last week's discussion of the ENCODE project, which is identifying just what it is that the ~99% of our genome that doesn't contain "genes" is up to.

The problem, of course, was the ENCODE claim that 80% of the human genome is "functional." Which on its face suggests that 80% is necessary, or at least important. Not so.

If you read only one explanation of what the fight is about, it should be the one provided by computational biologist Sean Eddy, now at HHMI's Janelia Farm. In enviably crystal-clear prose, Eddy uses his blog Cryptogenomicon to illuminate, among other things, why organisms, even closely related organisms, can possess dramatically different amounts of DNA and why much of it is nonfunctional transposons.

Some creatures, like pufferfish, have only low loads of transposons. Some creatures, like salamanders, lungfish, amoebae, corn, and lilies, are loaded with massive numbers of transposons. As it happens, the human genome is annotated as about 50% transposon-derived sequence — right at that 50/50 borderline where someone can say “the human genome is mostly junk” and someone else can say “the human genome is mostly not junk”.

Brian Maher's fine piece at the Nature Newsblog, which updates his fine feature of the week before, focuses this time on refining the meaning of "functional." Is noncoding DNA just spinning its wheels, or is it accomplishing something? Ed Yong has substantially updated his explanatory Not Exactly Rocket Science post, which I recommended here last week. It now includes many more critical comments and also explores exactly what "functional" means.

It's been cited several places already, but science writers everywhere ought to read John Timmer's Ars Technica dissection of the PR hype that helped shape the exceptionally inaccurate press coverage of ENCODE. Timmer's conclusion:

Many press reports that resulted painted an entirely fictitious history of biology's past, along with a misleading picture of its present. As a result, the public that relied on those press reports now has a completely mistaken view of our current state of knowledge (this happens to be the exact opposite of what journalism is intended to accomplish). But you can't entirely blame the press in this case. They were egged on by the journals and university press offices that promoted the work — and, in some cases, the scientists themselves.

Timmer blames ENCODE scientists for not making it clear to their press offices what "functional" really meant, and blames the press offices for not making sure they understood it. This episode, complete with backlash, is reminding me strongly of what happened after the announcement of the arsenic bacterium in 2010. There, too, many in the MSM got it wrong, but they were inveigled into their mistakes by PR machinations and misstatements by the scientists involved.

There's some worry that the backlash against the way the data were presented to the public may lead people to conclude that ENCODE is not, after all, a Big Deal and is even untrustworthy. But despite the hype and surface similarity to the sorry arsenic bacterium story, ENCODE is a Big Deal, and the databases it has assembled have been praised unanimously by those who will use them. Eddy again:

The ENCODE project and our existing knowledge of genomes are both vastly more substantial than the discussion the ENCODE authors are provoking in the press right now.

In a comment on Eddy's post, uber-geneticist David Botstein warns

I think all this should be sent to [N]ature as rebuttal. I also, think it is an object lesson that hyping one’s own work in the hope of impressing Congress is very likely to backfire... we scientists need to strive for objectivity as best we can lest we make ourselves no longer credible.