On science blogs this week: Radiation

RADIATION 24-7. For a comprehensive roundup covering many points of this huge tale, the aftermath of Japan's record-shattering earthquake, tsunami, and dangerous breakdowns at nuclear power plants, consult Richard Black at the BBC's Earth Watch. Black is summing up the situation in Japan before going on leave. This after two weeks covering the earthquake, tsunami, and aftermath, a week of it spent "virtually living inside the Fukushima nuclear power station," he says. I'm not sure what Black means by "virtually." Was he literally in or near the plant all that time, or was he monitoring events closely but remotely?

Still, this is a sane and reasonable-sounding overview, to be prized when lots of reports are over the top, not to say going off the deep end and hitting bottom. For distressing examples of media meltdown (all Brit, but that doesn't mean other nationalities didn't indulge too), see Fiona Fox's post at the BBC College of Journalism.

Rounding up the recent news on radiation and health at The Pump Handle, a public health blog, Liz Borokowski samples a handful of newspapers and Nature News.

But in a roundup at The Great Beyond, Declan Butler declares

there is now so much disparate data from many sources, in different units, and on various aspects of radiation, that there still seems much confusion about what it all means, and although a clearer picture is slowly emerging even experts sometimes don't seem sure and are awaiting further data.

As usual, some folks aren't waiting for data. At NPR's Shots, Richard Knox reports on a kind of citizen science, an effort in the US to get people to buy Geiger counters and crowdsource radiation levels drifting in from Japan. Always assuming they do drift in from Japan. Knox asks

Is this a good idea? Or the latest example of garbage in producing garbage out?

I'd say the answer to that one isn't very complicated.

Other species have problems more immediate than radiation. Shireen Gonzaga has a long post, with many photos, of the tsunami's effects on wildlife at the Midway atoll. Midway is 2400 miles from the earthquake epicenter, but the tsunami arrived at the low-lying islands just 5 hours later.

WATER, WATER EVERYWHERE, NOR ANY DROP TO DRINK. On Wednesday Japanese officials warned that radioactive iodine in Tokyo's drinking water exceeded standards for infants' chronic radiation exposure. Yesterday the officials rescinded the warning. But perhaps too late to prevent lasting stress, according to some experts. "Overnight, Tokyo transformed into the world's largest psychological laboratory," says Paul Voosen of Greenwire. Young mothers are particularly at risk, he says. It's a long piece, and his chief source is Evelyn Bromet, a psychiatric epidemiologist at New York's Stony Brook University, who studies the mental health effects of past nuclear crises.

OTOH, at Dot Earth, Andrew Revkin collects expert commentary too, on what he is calling the dread-to-risk ratio where radiation is involved. Revkin says:

Japan, sadly — and perhaps unavoidably — has been experiencing waves of what might be called warning whiplash, echoing (again) my Tweet from the other day: @revkin: Japan to citizens: Freak out, but stay calm. (http://j.mp/nukemilk).

The skeptical viewpoint got a hearing at NPR's Shots too. Richard Knox interviewed Evan Douple, the associate research chief at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, which has been studying the health results of the atomic bombs the US dropped on Japan to end World War II for 60 years. Says Douple:

once the dose estimates are put together and extrapolated, you should be able to make a crude estimate of the health effects ... I think that estimate will surprise a lot of people.

Knox: And they'll be surprised because?

Douple: They're so low.

IN THE PRIMORDIAL SOUP, THE ORIGIN OF LIFE. I'm a little surprised that there's next to no bloggery about this week's PNAS paper reporting on previously unknown samples from Stanley Miller's famous experiments of half a century ago.

You've heard about the Miller experiments; everybody has. In the middle of the last century, Miller and his colleagues zapped gases thought to resemble the early Earth atmosphere with electricity and in a week generated several amino acids. This was regarded as a demonstration of how organic molecules could have come into being on our then-lifeless (but gassy and lightning-struck) planet.

Miller repeated the experiment in 1958 using a mixture of methane, ammonia, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide that probably resembled gases emitted from early volcanoes. But he never analyzed the results. He put them in vials and shelved them. There they remained for the next 50 years.

The vials have been studied at last. The PNAS paper reports that they contained 23 amino acids, more than the number found in the original experiments and several important for life. There were both left- and right-handed examples of some amino acids in the vials, demonstrating that this bounty could not be the result of microbial contamination because organisms contain only left-handed versions. (Much of this information came from Sid Perkins's piece in ScienceNow.)

So here's evidence that life could have originated around volcanoes — although the study doesn't rule out other popular origin-of-life theories: for example that life-as-we-know-it could have arisen around hydrothermal vents or arrived from the stars, borne on meteorites.

This paper seemed to me of more than historical interest, but hardly anyone else thought so. For a moment it looked as if climate controversialist Anthony Watts, of Watts Up With That?, had written about it, and I looked forward to reading his distinctive take with a frisson of pleasure. But it was not to be. He was just reprinting a press release from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography..

Without, let me point out, making it terribly clear that it was not written by him, and I wonder how many readers assumed it was. I note that it got 14 5-star votes on Watts's site, which should, in a way, make the anonymous author of the Scripps press release feel good.

Danielle Venton discussed the new findings at Wired Science. She quotes former Miller student Jim Cleaves, a geochemist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who took over Miller's lab and participated in the reanalysis.

Sitting on the shelf was this box, I thought, "I don’t know what these are, but I can’t bear to throw them out!”

Always happy to confirm the utility of pack-rattery.

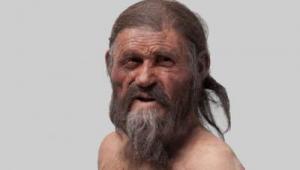

THE ORIGIN OF ANTHROPOGENIC GLOBAL WARMING. Today's photo is a reconstruction of what the Iceman Otzi might have looked like. You remember Otzi, whose 5,000-year-old mummy was found in the Alps two decades ago. I hadn't kept up, but as Emily Willingham informs us at EarthSky, Otzi led a full, not to say harrowing, life.

Estimated to be 46 years old at his death — I wonder how they arrived at that precision? — Otzi was an old man for his day. He was murdered, an arrow in his back, and suffered previous injuries too, not to mention parasitic worms, atherosclerosis, and severe arthritis.

It's odd that his murderer(s) didn't rob him of his beautifully made tools, which doubtless were valuable. They included a large, quite powerful bow and a copper axe.

Otzi is also said to have cooked food over coal. I didn't know coal was in use 5,000 years ago. Aha. Here we have the beginnings of anthropogenic global warming.