On science blogs this week: Revival

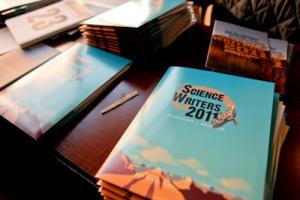

PIX AND PIXELS FROM SCIENCEWRITERS2011. Just back from Flagstaff AZ and the annual meeting of the National Association of Science Writers, that's us.

ScienceWriters2011 combined NASW professional workshops with the New Horizons in Science smorgasbord from the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing, and this year our genial host was Northern Arizona University. Reports of the NASW sessions have already been posted on the NASW web site, and dozens of photos are on Facebook. Find the Twitter feed @sciwri11.

FOR MALARIA, THE END IS NEAR(ER). One of the reasons blogging seems tailor-made for science is how well adapted it is for delving into complexities and wandering into intriguing byways, clarifying and enriching the complicated tales that scientists tell. This week's case in point is malaria, a parasitical disease that attacks hundreds of millions every year and is one of the world's great killers —especially of children.

You will, of course, have heard the very good news about the big clinical trial of the malaria vaccine, which prevented this grim disease in about half the little kids who received it. Bloggers extended the story with illuminating details of the sort that don't make it into MSM accounts.

Get the basics from Shari Roan at the Los Angeles Times blog Booster Shots. At Neurologica, Steven Novella muses on whether the vaccine might reduce the malaria parasite population by disrupting its life cycle even if it protects only half the population.

Or perhaps, Novella says, that outcome is unlikely because the disease infects other animals too. At the Nature Newsblog, Brian Owens brings us the latest on the controversy about the major natural reservoir for malaria parasites. The evidence still appears to favor gorillas.

In the process of describing approaches to developing a disease vaccine and giving two cheers for this one, retrovirus specialist Abbie Smith offers one of the clearest definitions of vaccines ever at ERV:

Conceptually, vaccines are very simple things — Dummy viruses/bacteria/pathogen that train your immune system how to fight the real viruses/bacteria/pathogen. All the benefits of being sick (training your B- and/or T-cells how to fight the pathogen) without actually having to get sick.

Melinda Gates describes how social media have made an impact on malaria in the Huffington Post. A Twitter-based campaign rounded up 100,000 bed nets that keep mosquitos, which carry the infectious malaria parasite, away from vulnerable sleepers.

SCIENCE JOURNALISM AT SCIWRI LABS. Seth Mnookin has launched a new feature of his PLoS blog, The Panic Virus. He's calling it SciWrite Labs, "an ongoing venue for researchers, reporters, public officials, and anyone else interested in science and science writing to debate the issues of the day."

That's a bit of a vague description, but the opening chapters are about a journalism issue particularly pertinent to science writing: Should a journo fact-check quotes and technical descriptions with a scientist-source? As any science journo knows, that's a perennially thorny professional conundrum, pitting accuracy against the potential for interference and bias and special pleading. It has resurfaced because of a blog post on that topic by David Kroll at Take As Directed, his PLoS blog.

The opening act at SciWrite Labs features an interview with Kroll and virologist Vincent Racaniello. The second installment, also an interview, is with Wired editor Adam Rogers and Ivan Oransky, executive editor at Reuters Health and founder or co-founder of two science blogs, Embargo Watch and Retraction Watch.

I suspect most science journos would come to this wishy-washy but reasonable conclusion: Sometimes. Carefully.

THE RESURRECTION AND THE LIFE. It took a little longer than the 3 days described in that well-known New Testament tale. But not much longer. The Scientist appears to be back from the dead just a week after life support had been withdrawn.

The rescuer who breathed life back into the pub rode in from Ontario and seems a sensible fit. As John Gever described the company on one of the NASW science writer listservs, LabX is a sort of Ebay for lab equipment. It also publishes Lab Manager, a trade magazine.

At The Scientist, Bob Grant makes clear that the deal is not yet quite final, but he sounds optimistic, so I will be optimistic too. As I told you when announcing its death a couple weeks ago, I was The Scientist's Founding Editor. Although I have had little to do with it for the past two decades except write a few pieces, I find I'm taking these events personally. I was disproportionately distressed when it died, and unreasonably buoyed to learn of its Resurrection. And death shall have no dominion!

Get details from Susan Young at the Nature Newsblog and/or Curtis Brainard at the Columbia Journalism Review's Observatory. Brainard observes:

One only hopes that the partnership won’t encourage the more technical side of the The Scientist’s personality too much. Its content is more accessible and engaging than general readers may realize. It would be nice to see its appeal grow broader, rather than narrower, as a result of its brush with death.

Brainard may like reading a less technical pub, but I'm dubious that approach would help The Scientist survive economically. General-interest science publications tend to go extinct. When we launched it in 1986, our idea was to do what organisms must to endure: occupy a vacant niche. So we attempted something no one had ever done before: creating a trade newspaper for scientists.

We had looked around and seen two trends: general-interest science magazines, even those launched gorgeously like the Science-backed Science '8n, had collapsed because they couldn't get advertising. By contrast, trade newspapers and magazines aimed at docs were fluorishing. There were no trades for scientists, so we invented one.

As I wrote in the 20th anniversary issue

[I]n the beginning, people thought it was weird that The Scientist wasn't about the glamour of discovery and gee-whiz-ain't-science-grand. Instead we were looking at science and scientists as struggling with the same issues that beset other lines of work: social trends, politics, the economy, employment ups and downs, and the desperate daily ordinariness of money, money, money.

The trade-paper approach must make sense, because now science journals and other professional science publications--and blogs, of course--consider those topics highly significant too. But in 1986, we had the niche pretty much to ourselves.

I like to think we changed the world. This world, anyway.