On science blogs this week: Shiga, Shiga

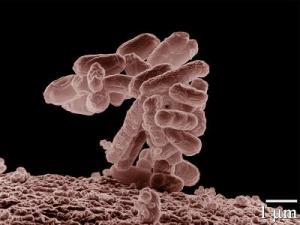

INSIDE THE OUTBREAKS. Here's one of my all-time favorite science factlets: Nine out of ten of the cells in your body aren't you at all. They're microbes. Of course without them you wouldn't be you either, because you couldn't exist. It's a microbe world, and we surely have been reminded of that here. Last week, the arsenic (not) bacterium and the XMR virus. This week, of course, deadly German variants of the normally friendly commensal, Escherichia coli, which has also long served benignly as one of science's premier model organisms.

I don't often do just one topic, but this exceptional outbreak of E. coli food poisoning demands it. That's partly because the last week illustrates brilliantly the utility of blogging for getting around and among and into a story in a way that MSM just can't. We are hearing this tale informally not only from stellar science writers, but also directly from scientists — an invaluable adjunct to the story that simply wouldn't be available any other way.

From the beginning in 2009, I've used this weekly post not just to round up some noteworthy blogging about science but as a running commentary about the 'Net's impact on science writing as a profession. At a minimum, it brings us brand-new (and previously unimaginable) sources of information and direct, unfiltered access to what scientists are thinking and saying about topics we care about and/or are writing about.

This week's best case in point is not exactly blogging, but so what? It's a crowd-sourcing wiki for analyzing the E. coli O104:H4 strain causing the current outbreak in Europe that started in Germany. Two isolates from the outbreak have been sequenced so far.

Note that these wiki analyses do not involve the bugs themselves. They're based on their genomes, which have been sequenced immediately thanks to scientific enthusiasm and spiffy new technologies that make sequencing fast and (relatively) cheap — in this case a desktop sequencer from Life Technologies. Plus — perhaps even more essential — a new open-access mindset that led the sequencers at the Beijing Genomics Institute and Life Technologies, and the University of Münster, to open their data to the world.

Most of this analysis is more than I can handle without interviewing and interpretation from scientist go-betweens. But even here in kindergarten I gotta say that in this very nasty world (and getting every day more nasty, not to mention violent, with a heap of the monumentally trivial for distraction), it gives me a frisson of pleasure to ponder these posts. They are very nearly the Platonic idea of how science should be done — collaboratively, and openly, and freely available, national borders and corporate borders be damned. It's cutting-edge crowdsourcing and it's an intellectual venture, but it has an impressive moral dimension, and the folks who are doing it are a credit to our species.

The E. coli strain in question is not the notorious O157:H7, which, despite its reputation since the Jack in the Box tainted meat scandal of the last century, does not usually cause sickness and is not often found in H. sap. Yet E. coli strain O104:H4 has sickened nearly three thousand people and killed more than 30 so far, the most deadly siege by E. coli ever recorded. It has turned up in more than a dozen European countries, and a few US cases have been brought home by travelers to Germany.

These bugs are enterohaemorrhagic, meaning they cause hemorrhaging in the gut. But some 800 of the patients are also suffering from the far more deadly haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS). HUS is due to Shiga toxins produced in the bugs. The toxin destroys red blood cells, causes neurological problems, and damages kidneys to the point of failure and death.

The assumption is that O104:H4 became so dangerous when it acquired new genes that cause the host gut to hemorrhage, confer antibiotic resistance, and — probably most important — came from bacteria-infecting viruses that produce the Shiga toxin the bacterium formerly lacked. This last is an especially intriguing point; more on it shortly.

SCIENCE WRITERS ARE SCARED. Last week, science writer Christine Gorman explained at Scientific American Observations "Why This E. Coli Outbreak Has Me Scared. She wanted to know where the strain came from and why adults (especially women) are particularly hard-hit. She also wondered about the likelihood that the already deadly strain will acquire antibiotic resistance and so become even more deadly.

Gorman's post was written early in the outbreak, before it was widely known that the bug is already resistant to many antibiotics. But it turns out that resistance doesn't matter much. At Superbug on Tuesday this week, Maryn McKenna helpfully lists what we know about this bug and what we don't. She notes that outbreaks involving Shiga toxins are not usually treated with antibiotics. Antibiotics kill the bugs dead, all right, but in dying they release floods of the lethal toxins, which is the very essence of counterproductive.

An extraordinary couple of blog posts come to us from someone who's not, formally, a science writer at all: Mark Bittman, long-time food writer at the New York Times. You will learn things from these that you will find nowhere else. Keep in mind that he is not a partisan of meat and is very very very opposed to the meat industry, but he's got his reasons.

When they first released sequence data, BGI officials asserted that this was a brand-new microbe. By last weekend, the experts were doubting it. The microbial ecologist Géo at The Alignment Gap supplied his reasons why. Géo also indulges in a nice primer on scientific nomenclature, aimed at journalists and emphasizing (and clarifying) the potential confusions of E. coli.

Mike the Mad Biologist doubted it too, saying that a very similar strain was isolated ten years ago. He complains:

While this is obviously a very preliminary analysis of a very preliminary assembly, I don't understand why this strain is being called 'new', 'mutant', or anything else. It's not a bolt from the blue: it looks like a nearly identical strain that caused HUS a decade ago in Europe. I would add the obvious qualifier that there very well could be massive gene gain and loss (I haven't looked at that yet). I'm guessing that the reports of this strain being very different were based on comparisons to the genomes of other HUS strains, which are pretty divergent.

National Public Radio has been following the story with several posts at its health blog, Shots. Richard Knox interviewed Centers for Disease Control officials and other food poisoning experts about the migration of Shiga toxin-producing ability to other strains of E. coli. In another post he described US success at reducing food poisoning outbreaks — except for salmonella, which has gotten worse.

Eliza Barclay described the process (and the problems) of tracing the source of food poisoning. Scott Hensley and April Fulton describe the dismal food safety picture in China and discuss what that means for the US, which imports a lot of Chinese garlic, tilapia, and apple juice. Fulton looks on the bright side. Perhaps, she speculates, the E. coli crisis will mean more money for heretofore-starved US food safety programs. From her lips to Congress's ears. But I doubt it. After all, it didn't happen here.

Not much comic relief to be found in the outbreak tale, but for something approaching it, see Siouxsie Wiles's Infectious Thoughts, which recounts a natural foods conspiracy theory declaring that Big Pharma engineered this outbreak in order to take control of the food supply and make people stop eating fruits and vegetables. Counter this with Marion Nestle at Food Politics, who provides a consumer-oriented Q&A about how to make your food, and everybody else's, safer.

I've got dozens of other relevant links, but already I've nattered on too long. Before I depart, however, a few words about Shiga toxin.

The gene that makes Shiga toxin is not a bacterial gene. It comes instead from the viruses that infect bacteria known as bacteriophage, phage for short. They are not much in vogue in the US, but in other parts of the world phage have been employed to fight disease-causing bacteria for more than a century. One exceptionally cool thing about phage is that they care only about bacteria; they can't even "see" human cells.

I came to be a phage fan via a couple of interviews with Vincent Fischetti at The Rockefeller University, who's working on enzymes from phage as a weapon against bacterial disease, and particularly against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. So I've been accustomed to thinking of phage as the Good Guys. But in this E. coli outbreak, it appears, it's the phage (or phage genes that have integrated into the bacterium's DNA) that are making the Shiga toxin that's making folks so sick. Mike the Mad Biologist tells you all about it, and also speculates that toxin-making phage are just as bad for their bacterial hosts as they are for their unlucky human ones.

I'm traveling on assignment next week, so au 'voir until June 24.