On science blogs this week: Zombies

ZOMBIE APOCALYPSE NEWS. Nobody knows more about parasites than that very superior science writer Carl Zimmer. So he is absolutely the right person to take on the suddenly extant notion (prompted, I guess, by that unspeakable Florida face-eating event and encouraged by some in the media), that parasitic organisms are invading people and turning them into cannibal zombies. Carl is not one to let a teachable moment slip past him, so he takes on zombie apocalypse news while also imparting a brief primer on what is known about parasite influence on host behavior.

We can only hope in particular that HuffPo's Andy Campbell will seek some career other than science writer after Carl's masterly disemboweling. Example:

The Huffington Post entitled Campbell’s hard-hitting investigation, “Zombie Apocalypse: CDC Denies Existence Of Zombies Despite Cannibal Incidents.” That’s perhaps the finest deployment of the word despite in the history of journalism.

I suppose Campbell will now have the chutzpah to claim he was trying to be funny. As they say in France, it is to laugh. There are honest, good-hearted people attempting to shoehorn trustworthy science into HuffPo, but Lordy, when drivel like this is permitted (encouraged?) in the same pub, how can their efforts possibly succeed?

THE RNA WORLD: IRON GAVE IT RNA ON STEROIDS. Before there was DNA on this planet, there was...RNA. Probably. Maybe. And if it was an RNA World, RNA may have worked differently than it does today. It may, for instance, have employed iron as an enzyme to help it behave in more complex ways than are permitted by the magnesium it uses now.

Two blog posts walk you through that possibility by analyzing a new PLoS One paper arguing that iron could "support an array of RNA structures and catalytic functions more diverse than RNA" with magnesium alone.

At Ars Technica, Melissae Fellet explains that in those pre-life days there was no photosynthesis and thus no oxygen, so iron didn't rust and instead dissolved in water, making it easily available.

At the Nature Newsblog, Helen Thompson reports that one of the paper's authors told her

We're used to our world of oxygen, and oxygen and iron is just a terrible combination. They make a hydroxyl radical, and everything it hits loses a hydrogen, shredding RNA and proteins too...RNA with iron is RNA on steroids.

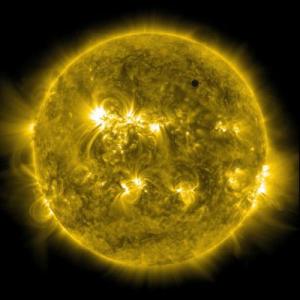

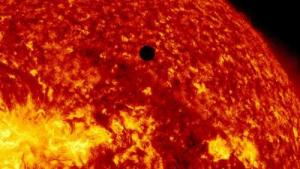

MORE ON THE TRANSIT OF VENUS. Phil Plait has assembled a gallery of awesome — in the old-fashioned sense of that ill-used word — photos of last Tuesday's Transit of Venus. Some are serious and some amusing. I have posted a couple of public-domain examples of serious photos here, but go see them all at Bad Astronomy.

There seems to have been near-universal fascination at this event, which, as I explained last week, was available on TV and online as well as in person. This despite the fact that Venus was a mere dot on the blazing face of the sun, nothing like the high drama of the eclipse a few weeks ago. I wonder if that has something to do with our knowledge that eclipses are not all that rare, but by the time the Transit happens again in 2117, everyone who saw it last Tuesday will be long dead. Sic transit indeed.

DEVISING AN ELEVATOR SPEECH ON SCIENTIFIC IGNORANCE. Michelle Nijhuis of Last Word on Nothing invites you to ponder a science profundity: the ignorance that is central to what scientists do, the things they don't know that they want to know.

This is not the sort of ignorance portrayed by climate change denialists who charge that scientists don't know enough about global warming, for example, to propose specific steps to cope with it — especially steps that will cost the denialists (or their backers) money. She is talking instead about ignorance that drives the desire to know more about how the world works, the questions scientists must think up to ask before they can answer them.

But Nijhuis notes that it's hard to explain these concepts briefly. She would like some help with the elevator speech about instances of productive scientific ignorance. She calls on you to

Send me examples of scientists talking about their kind of uncertainty and doubt in a convincing and extra-pithy way. Or tell me what you think scientists should say about the ignorance that drives them.

SEXUAL DIVISION OF LABOR — aka SEXISM — IN NEUROSCIENCE. Also at that fine group blog Last Word on Nothing, science writer Virginia Hughes would like to know the whys of gender patterns among neuroscientists. She notes that most of the neuroscientists she interviews are male. Among the possible explanations she proposes: She tends to interview lab heads, and at this point in neuroscience history, they are still nearly all men.

But she has noticed a new pattern recently and wonders if it's a trend. For her latest piece, half her interviewees were women. She notes several reasons why the proportion of women neuroscientists may be changing.

The reasons all seem plausible. But what struck me is that Hughes's recent experience involved researchers in a new field of neuroscience. I suspect the novelty of a field is part of the explanation — perhaps a big part — for why so many of its researchers are women.

New areas of endeavor — and I'm pretty sure this applies not only to science but to scholarly fields in general and probably also to other lines of work — don't come with preconceived ideas of exactly what the work should consist of, how it should be done, and who should do it. The first folks to enter a new field are making it up as they go along. Novelty is risky, and the potential rewards that could make it worthwhile may not be apparent at first. Also, new fields don't come with an established work force to compete with.

This explanation is almost mechanical: in a new field (of research, for example) there are simply fewer barriers to entry and an absence of existing models for how things should be done. Flexibility and openness are part of the picture from the outset.

Things won't, of course, stay that way. When a field gets hot and the rewards become obvious, everybody wants in. Sharp elbows are a competitive advantage. Hierarchies become established and so do credentials. The old boy network coagulates.

I am willing to bet a small amount of money that, if the field of neuroscience Hughes was writing about, microglia, retains its glow, in 10 years women scientists doing that work will once again be outnumbered.

Oh man, would I love to be wrong.