On science blogs: Deadly virus and long-dead animals

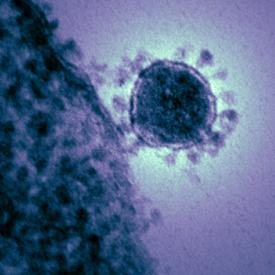

THAT NEW DEADLY CORONAVIRUS IS NOW IN THE UK. Researchers have no idea whether the new coronavirus HCoV-EMC will end up resembling its cousin, SARS, responsible for the severe acute respiratory syndrome of a decade ago. But HCoV-EMC has already killed 9 of the 15 people it is known to have infected, and it has spread from the Arabian Peninsula to the UK. So we are now at the early stage where the virus seems as if it might be very scary indeed. No US cases have been reported yet.

HCoV-EMC is believed to have arisen in bats, like SARS, and jumped from bats to people, possibly with help from another animal intermediary. But as Stephen Baum points out at Journal Watch, the UK cases are evidence of person-to-person transmission. Which kicks HCoV-EMC into an even more worrying category.

In a Loom post describing research on the evolution of HCoV-EMC, Carl Zimmer provides a bit of reassurance, pointing out that many people have had contact with those infected without falling ill. We can hope that's where the story ends, but at this point there's no way to tell.

Researchers have moved quickly to identify the cell receptor that allows HCoV-EMC to invade human cells. The Nature paper was published just last week, work described by Vincent Racaniello at his Virology Blog. The receptor is a transmembrane protein regulating hormones and chemokines that figure in the body's immune responses. The researchers speculate that the receptor might remove cytokines that protect against virus replication and tissue damage.

Superbug's Maryn McKenna has, of course, been on top of this story early and often. In a post last September, she explained why HCoV-EMC's resemblance to SARS was making infectious disease specialists so nervous. In October she reported on the first peer-reviewed papers on the new coronavirus, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. It was an occasion to ruminate about the communication process for new disease organisms and, a tough one, how to explain the uncertainties to the public. In her most recent post in December, she described work showing that the virus can infect bats and pigs as well as people, an uncommon versatility and one that could make it more difficult to track.

And then there are the human factors. At Ars Technica, Allie Wilkinson describes the tracking system for emerging diseases set up by the World Health Organization in the wake of the SARS experience. 195 countries agreed to participate by setting up basic systems for detecting and dealing with threats to public health. So far, 119 of them have failed to meet the deadlines.

DE-EXTINCTION DEBATE. Knight Science Journalism Tracker Paul Raeburn complained about lack of media coverage of the meeting on bringing back the dead, foreshadowed here last week. I suspect that absence may turn out to be true for immediate daily coverage only. It was a day-long meeting, even for those following the live-stream in their jammies. In these straitened times, few assignment editors are going to blow a staffer's entire day on reporting a single brief news story. Pressures are even more dire for freelances, for whom time is now money in the most literal way.

I expect we may eventually see feature stories growing out of the meeting, although they will have to work hard to do the job as well as Carl Zimmer's anticipatory cover story in the April NatGeo. It is blessedly not behind a paywall, or at least not yet. I laughed out loud when I read the last graf, which makes exactly the same point I did last week about the motive behind de-extinction. Why bring back extinct organisms? Because it's cool. See also his Q&A post at The Loom.

The live-stream event is still available here as I write. How long that will be the case I do not know. Edited videos are supposed to go up on YouTube eventually. There's also a NatGeo aggregation page of photos and links to blog posts, podcasts, opinion pieces, polls, etc. etc. The once-august and snobby National Geographic Society is pushing all the media buttons on this one.

And you can always count on blogging. Nadine Lymn, public affairs officer for the Ecological Society of America, is using the meeting to launch a series of posts about reviving genetic diversity. In her first post she focused on two of the meeting's themes: whether reviving the extinct could make saving endangered species even harder than it is already, and how gene technology could help save them.

Last week I linked to Brian Switek's Laelaps post pointing out that, with the Ice Age long gone, a woolly mammoth would have no place to live. Paleoecologist Jacquelyn Gill expands on that theme in her SciAm guest blog, posing questions she calls both practical and philosophical:

What is a woolly mammoth, really? Is one lonely calf, raised in captivity and without the context of its herd and environment, really a mammoth? Does it matter that there are no mammoth matriarchs to nurse that calf, to inoculate it with necessary gut bacteria, to teach it how to care for itself, how to speak with other mammoths, where the ancestral migration paths are, and how to avoid sinkholes and find water? Does it matter that the permafrost is melting, and that the mammoth steppe is gone?

Attending the meeting not only didn't change Switek's mind about the wisdom of de-extinction, it left him even angrier. A speaker had justified it as "restoring the balance of nature," which Switek correctly identified as hogwash. Read the entire Laelaps fulmination, but this will give you the flavor:

[T]hat one line underscored the problematic nature of the major proposal the assembled speakers and guests had been called to consider – that we can, and should, resurrect lost life to take some of the tarnish off our ecological souls.

In a Technology Review post about efforts to resurrect the passenger pigeon, Antonio Ragalado said conservation biologist David Ehrenfeld

noted that there are currently conservationists risking their lives to save the last African elephants from heavily armed poachers: “So why are we sitting in this auditorium talking about bringing back the woolly mammoth? Think about it.”

Despite the naysayers, it appears this drive to bring back the dead, and become media fodder in the process, is not itself about to die. The hope of being cool is tough to abandon.

Also, Regalado reports, capitalism has entered the picture. Two of biotechnology's biggest stars, stem-cell pioneer Robert Lanza and Harvard DNA guru George Church, have founded a start-up they have named Ark Corp. The goal appears to be dabbling in de-extinction, but the main plan is breeding specialized animals such as dogs with lifespans of 20 years or creating biofactories that could keep producing sperm from prize livestock after death.

Ultimately, perhaps, the reproductive technologies devised to bring back disappeared organisms might bring new approaches to human reproduction. Regalado suggests that one possibility might be giving homosexual couples a child with genes from both parents.