On science blogs this week: Bits

FOR GENE THERAPY, SOME SUCCESS AT LAST WITH HEMOPHILIA. The gene therapy folks have been at it for many years with not a lot to show for their efforts. The principle behind gene therapy is not complicated: to cure a disease caused by a gene that's misbehaving, give the patient a gene that works. The practice, however, has been devilishly difficult. How do you get the working gene into the patient? How do you make sure it ends up in the right place? How do you keep it from doing harm? How do you get it to make the right amount of its product? How do you ensure that the product fixes the problem?

This week researchers reported the first unambiguous success for gene therapy after several attempts with a number of diseases and a quarter-century of frustration. It was a small study, just six patients given gene therapy for the blood-clotting disease hemophilia B. But the treatment was strikingly successful — successful enough to be published in the much-venerated New England Journal of Medicine, a signal vote of confidence.

Four of the six began to make enough of the missing factor that helps blood clot to stop standard hemophilia therapy, which is frequent and extremely expensive injections of the missing clotting factor that can cost $20 million over a lifetime. The other two made enough to cut back injections from several times a week to every couple of weeks.

These good results have persisted in 5 of the patients for going on 2 years, although it's not clear yet that the new gene is a permanent cure. Get details from Ewen Callaway at the Nature Newsblog, and Veronique Greenwood at 80 Beats and Mark Hollmer at FierceBiotech Research.

And see virologist Abbie Smith crow with delight at ERV. The good gene was ferried into the patients by a harmless adeno-associated virus, demonstrating that viruses don't only cause diseases, they can cure them. She also points out an unfortunate side effect: this gene therapy is a one-shot deal. That's because, as it does its good work of gene delivery, the virus will also provoke the patient's immune system into making antibodies against any future encounters.

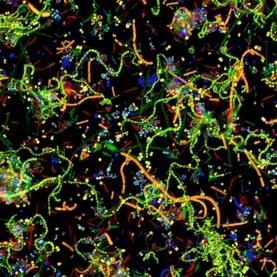

CLASSY CLASI: COLOR-CODING FOR MICROORGANISMS. I confess I selected this post from Katherine Harmon on SciAm's Observations blog mostly because of the nifty illustration. It accompanied a presentation at the recent American Society for Cell Biology's annual meeting describing a new technique for labeling microbes that color-codes by taxon. In this case, they were microbes found normally in the human mouth, some of which cause oral disease like periodontitis, with eventual tooth loss.

The color-coding is not just pretty, it shows which species of microbes hang out with each other. Chumminess like this is a potential clue to disease. The researchers found that Actinomyces, a cause of oral infection, spends time in the company of Prevotella, which seems to be involved in respiratory infections. That suggests that the bug combination likely figures in plaque, the biofilm that causes gum disease.

Combinatorial Labeling and Spectral Imaging (CLASI) was developed by researchers at the Marine Biological Laboratory and Brown University. The technique has applications far beyond the mouth.

Microorganisms tend to live in complex communities that researchers are only beginning to sort out, and CLASI is a tool that might help with the sorting. Microbes in the human gut, for example, are now suspected of figuring in diseases not generally thought of as infections, like cancers. But they also influence the immune system's response in other parts of the body. And, most spookily, there's some experimental evidence that they can affect behavior, too.

ONCE MORE, THE HIGGS BOSON. Oh Lord, that pesky Higgs. The all-important meeting described here last week did indeed take place last Tuesday. It revealed that two rival research groups are reporting a bit more evidence for the existence of the Higgs boson than there was before. But they haven't nailed it yet.

The most useful illumination about this particle physics quest I got this week came through a scientist in quite another field: paleontology. John Hawks helpfully linked to a Guardian piece by physicist Lawrence Krauss.

Krauss explained the research clearly, emphasizing what he thinks are its potential immodest implications:

it will represent perhaps one of the greatest triumphs of the human intellect in recent memory, vindicating 50 years spent building one of the greatest theoretical edifices in all of science and requiring the construction of the most complicated machine that has ever been made.

But Krauss also explained why finding just one Higgs particle won't be enough. The folks beavering away at the very large Large Hadron Collider really need two of them.

Aaaaargh.

I know, I know, the contention is that the Higgs particle(s) is(are) truly the Answer(s) to Life, the Universe, and Everything. Still, I acknowledge a certain fellow-feeling with the first guy to deposit a comment at the foot of the Krauss piece: "I'm tired of this hype — call me when there is real news."

SEE YOU NEXT YEAR. I'm taking time off and will next be back in these precincts on January 6, 2012. You're not going to be doing much reading for the next couple of weeks anyway, right? Be jolly.