On science blogs this week: Scandal 2

PROMINENT CLIMATE-CHANGE DENIER NOW ADMITS HE WAS WRONG. "Call me a converted skeptic," Richard Muller said, the first sentence of his op-ed in last Sunday's New York Times. I have cribbed my hed from the Christian Science Monitor, which put it the same way: "Prominent climate change denier now admits he was wrong (+video)."

Plus video. An exquisitely persuasive detail. Do you suppose future climate historians, assuming there are any future climate historians, will declare that Muller's Times op-ed was the tipping point? The moment when the affray over whether Homo sap is to blame for global warming was transfigured into an affray over what to do about it?

From his lips to God's ear. Not, God knows, that the scientific dispute is at an end. The usual combatants leapt right in, and I'll get to them in a moment. But it's an interesting question whether Muller's media-savvy conversion, high-profile enough to be second only to St Paul's on the road to Damascus, will be persuasive to the uninformed electorate.

My hunch is it may have some effect on public opinion and, eventually, even on policy.

We already know that more science is unlikely to do the job itself. But the fact that the science has caused a self-proclaimed climate-change skeptic to self-proclaim his about-face, and to do it in a most visible way — that's powerful stuff with great emotional appeal.

What's more, while the climate bloggers and their followers are dedicated, argumentative, and masters of intricate and abstruse climatological detail, the rest of us are not. The message delivered to the general public arrives in bulleted form like the Monitor hed I quoted above: Prominent climate change denier now admits he was wrong (+video). This is, to use an old-fashioned journalism term, just Jigsaw News, free of nuance. But as we all know, Jigsaw News is what most people hear and retain.

Now to the blogging:

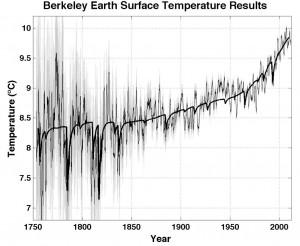

At the Nature Newsblog, Jeff Tollefson describes what Muller was writing about, the Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature (BEST) project's most recent study. (Why do I suspect that the project title was chosen for its acronym?) Tollefson pointed out that none of the papers has yet been published and quoted a reviewer revealing that at least one of the studies has been rejected by the Journal of Geophysical Research. At Carbon Brief, Verity Payne details the recent BEST study findings too, along with a paper from the Watts group described in the next graf. She also quotes critiques and emphasizes that neither paper has been published.

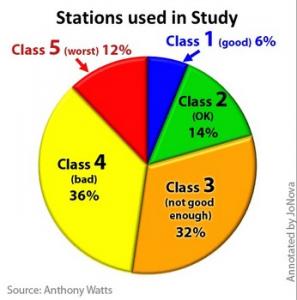

At Andrew Revkin's Dot Earth, also at the Times, find his take on Muller's op-ed, the BEST study, and the other study, led by WattsUpWithThat blogger Anthony Watts, which contends that the stations that measure temperature have been sited so poorly that their data are not to be trusted. Revkin links to other posts of his own and several outside critiques. He has a forecast too, about the BEST work:

... Muller's database will hold up as a powerful added tool for assessing land-side climate patterns, but his confidence level on the human element in recent climate change will not. I'd be happy to be proved wrong, mind you.

At Ars Technica, John Timmer describes how the BEST people arrived at that conclusion, which he calls "not exactly a sophisticated analysis":

[T]hey use an incredibly simplistic approach: start with the baseline temperature, add volcanic eruptions, then add other climate forcings to see which one recapitulates the temperature curve. They conclude greenhouse gasses fit the best (and more or less rule out solar variations as major drivers), although they note that carbon dioxide is serving as a proxy for a variety of human-driven changes.

Timmer also thinks they may have a hard time getting their papers published because the work overlaps so much with previously published studies.

Climatologist and climate-change gadfly Judith Curry notes at her blog Climate Etc. that Muller's analysis leaves her unconvinced that warming can be ascribed mostly to human activities. Curry is a BEST person, but she declined to be an author on this paper for that reason. In this post she goes into detail on the challenges scientists face in attributing climate change to particular causes.

Watts was happy to post a video of Muller recounting his conversion on Rachel Maddow's show. That's because it gave Watts an opportunity to point out that Muller ignored the problem of weather station siting, and to comment smugly, "I think my message was delivered."

Brad Plumer's Wonkblog post takes up the question of why these papers should be getting so much attention, given that neither has been published. Scientifically speaking, his sources say, they're not really so important that the news couldn't wait for the review process to grind away. He doesn't really answer his own question out loud, but implies that the answer is PR. Shocking. Do you suppose people who named their group so it would yield the acronym BEST are really capable of thinking that way?

The reason for the timing of these two announcements seems pretty obvious to me. They came just before Wednesday's Senate hearing on the latest climate-change science. David Appell linked to the webcast and live-blogged the hearing at Quark Soup. In another post, Appell points out that, although the Watts group paper has serious flaws detailed by others, its findings were, oddly enough, acceptable as testimony at the hearing. The testimony was by Watts's co-author, climatologist John Christy, and Judith Curry has posted a mild analysis of it.

There's much, much more, but I've had enough. You're on your own.

CURIOSITY LANDS ON MARS SUNDAY-MONDAY. FINGERS CROSSED. Babbage calls it seven minutes of terror, and so do several other bloggers, including me. We all stole that irresistible phrase from the title of a video made at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Seven minutes is the time it will take for the signal from Curiosity, the latest (and, it looks like, last) Mars rover, to reach those of us waiting for the news here on Earth that it has landed safely. Babbage puts it colorfully:

[B]y the time NASA’s engineers receive a signal that the rover has entered the upper layers of the Martian atmosphere, the rover will already be sitting on the ground—or else smoking in bits at the bottom of Mars’s newest, and most expensive, crater.

In this case, no news will not be good news. The Babbage post explains succinctly why the plans for landing big fat Curiosity with a skycrane are so much iffier than the landings of its successful gracile predecessors Sojourner, Spirit, and Opportunity. And the video explains it too, not all that reassuringly. Says JPL engineer Adam Steltzner of the skycrane, "It is the result of reasoned engineering thought. But it still looks crazy." Yup.

Spend a few minutes on the Bad Astronomy site watching the American Chemical Society explain what Curiosity will be doing once it lands safely, let's be positive here. Curiosity, it says, is the next best thing to shipping a bunch of trained analytical chemists to Mars to look for signs that life (of the microbial sort) ever lived there. You can also wonder, along with me, if ACS honchos knew that the opening narration — forecasting that "future events such as these will affect you in the future" — was lifted from what has been described as the Worst Movie Ever Made, Plan 9 from Outer Space.

And join Phil Plait, the Bad Astronomer himself, plus a whole lot of other people, who will be at a Google+ hangout waiting around for the landing late Sunday night and into Monday morning, depending on your time zone. The landing is scheduled for 1:31am Monday EDT, and the hangout begins at 11pm Sunday EDT. Plait has also posted on places you can watch and spend your own seven minutes of terror

AU 'VOIR CHARLIE MON PETIT. Catch up with what the MSM have been saying about Curiosity at Charlie Petit's post at the Knight Science Journalism Tracker. The post will also tell you that today is Charlie's last formal day as a Tracker. Charlie has long been the chief and most prolific of the Knight group assessing science journalism on the wing. Today he retires, but he assures us he'll be back occasionally, which is good news. His successor as chief tracker is an old hand, Paul Raeburn. The Knight Center has also redesigned its site, including a spiffy new look for Tracker posts. Check it out.

JONAH LEHRER MOVES ON TO MAKING THINGS UP. As you know, prominent science writer Jonah Lehrer has been caught making up Bob Dylan quotes in his most recent book, Imagine, and then lying about it in a pretty bare-faced way, and then coming clean in the usual self-abasing way, and then getting fired from just about the best job in journalism, writing for the New Yorker. For a cogent summary, consult Paul Raeburn's post at the Knight Science Journalism Tracker. Paul is a little puzzled about why Lehrer set his sights so low:

Lehrer's sin is roughly equivalent to a bank robber breaking into a parking meter. If you're going to fabricate, go for it, man. A new theory of consciousness! Alien abductions! Make it count.

This event follows on the previous uproar about Lehrer, the charge that he recycled his work, discussed here a while back. Which he did, but a lot of the rest of us reuse stuff too, and why not; it's our stuff. This latest thing is another matter altogether: making things up is not kosher when the piece is supposed to be non-fiction.

The Why Did He Do It mill has been grinding away, and it has churned out a remarkable amount of psychologizing hogwash. Leading me to declare that not only should we halt media speculations about the motives of mass murderers, we should also stop trotting them out when writers go wrong.

At the Columbia Journalism Review's Observatory, Curtis Brainard analyzes some of the swill. For example, the Salon piece declaring that Lehrer is emblematic of a systemic problem, a societal seeking of boy geniuses. And the interview with Jason Blair, former top fabricator at the New York Times and now — wait for it — a Life Coach, declaring that Lehrer, along with Blair himself, were victimized by their own impossibly high expectations for themselves. And the Atlantic piece declaring that it's all our fault because we want gods.

No.

Stanton Peele says the problem is that Lehrer's writing about neuroscience was simplistic, contradictory, and sometimes silly — for example attributing to 19th century novelist George Eliot the discovery of neurogenesis. Ipso facto, catching him in dishonesty is not surprising.

No. I wonder how Peele explains the notorious fabrications by others — Blair, Glass, Cooke et al — who were not writing about neuroscience?

At Big Think, Steven Mazie draws inspiration from Lehrer's writings discussing the neuroscience of self-deception, declaring "One of his most recent blog posts reads today as a self-diagnosis, or even an admission of guilt." Mazie imagines the scene where Lehrer invents the Dylan quote, arguing that he was channeling Dylan:

Lehrer’s creative process merged with that of his subject. Lehrer became Dylan. And Lehrer’s abstract reasoning process ... failed to boot up. Lehrer just moved on to the next paragraph, happy with what he had created, deluding himself that fabricating the perfect quote and attributing it to a cultural icon is anything but a terrible idea.

No. Although I wouldn't be astounded if something like this turns up in Lehrer's inevitable confessional book.

Enough. The big Why question for me is Why do people do this? Write this claptrap, I mean.

At Last Word on Nothing, Christie Aschwanden evaluates the prospects for Lehrer's return to grace and outlines the steps he must take to get there. She is certainly right that rehab will depend on the extent of his lies. If the Dylan thing turns out to be the only example, I foresee some kind of redemption. The search is doubtless on for other Lehrer fictions, and if they turn out to be numerous and habitual, return to respectability as a writer is probably not on despite that confessional book contract.

I don't think the answer to Why? is anything like as complex or deep or Freudian as the speculations suggest. Imagining the process as Mazie did, what I come up with is this: Cooking up material has a pretty simple motive, very nearly a practical one. It comes from trying to write terrifically sexy, startling stuff too fast and too much.

When you're a freelance, you don't dare turn an assignment down. Yes, I can do the piece on the very technical topic I know squat about. And yes, I can do it by tomorrow. Then desperation sets in. The writer has got to turn in the damn thing on time because the ability to meet deadlines is nearly as important to his reputation with editors as the ability to write.

When impossibly pressed for time and probably short on sleep, it must be pretty easy to slide into making things up and lifting material from elsewhere. It is actually a pragmatic move. There's quite a good chance he won't get caught, or that's what he tells himself. And until recently it's been true.

Let's close this sorry tale with a gem from The Onion. (HT Jeff Hecht.) Fair warning, though: It's too near the bone to be funny.